SUMMARY

UNIFYING THEME: Information Marketplace: Ensuring the Public has the Data

Minimizing the personal and economic costs of a global pandemic requires the coordination of federal, state and local governments. When it comes to implementing stay-at-home orders with the simultaneous and competing goals of minimizing community spread and business dislocation, our data-driven analysis demonstrates the value of public policy discretion at the state and local level.

RELATED NEWS:

by Mario J. Crucini, Professor of Economics and Oscar O'Flaherty, Ph.D. Candidate in Economics

With the global COVID-19 pandemic approaching its first anniversary, hope is on the horizon as increasing numbers of Americans have access to vaccines. However, because of new emerging virus strains, limited vaccine supply chains and hesitancy among some population segments, the precise timeline for achieving herd immunity remains murky. Given this uncertainty, public health officials will continue to face the daunting and competing challenges of encouraging responsible social distancing and minimizing economic dislocation for the foreseeable future.[1].

Throughout the pandemic, stay-at-home orders have been effective in limiting personal contact and combating the spread of the virus. While such policies demonstrably flatten the COVID-19 infection growth curve, they come with high societal and economic costs.

Protests over the economic impact of stay-at-home orders occurred in many states.[2][3] One protester in New Jersey said, "Businesses are suffering, unemployment checks are not being sent, landlords are not getting rent. We feel like these directives are causing more suffering than is necessary."[4] A poll conducted in May 2020 estimated that 35 percent of people "strongly or somewhat agreed" that restrictions and closures had been too severe.[5]

The country was also divided about how stay-at-home orders should be implemented. A poll by The Economist in April 2020 showed that 61 percent of people believed that President Donald Trump should issue a national stay-at-home order.[6] At the time, the president opposed a nationwide order, saying, "There are some states that are different. There are some states that don't have much of a problem . . . You have to give a little bit of flexibility."[7] However, Dr. Anthony Fauci expressed a different opinion, saying, "I just don't understand why we're not doing that [issuing a federally mandated stay-at-home order]. We really should be."[8]

In the case of stay-at-home orders, where the health versus wealth effects are stark, achieving unanimity is likely impossible. Tradeoffs do exist. Understanding and acknowledging these tradeoffs from an evidence-based standpoint is a crucial first step in narrowing the public opinion divide.

Novel contributions to data dissemination and macroeconomic modeling have made it possible to empirically examine the health and economic tradeoffs throughout the pandemic. Private companies, such as Homebase, released high-frequency data essential to measuring the ongoing economic impact of COVID-19. Previously, researchers had commonly had to wait weeks or even months before seeing the most up-to-date employment numbers. Much of the data from these companies was compiled into a publicly available database by Opportunity Insights.

On the modeling front, Martin Eichenbaum and his co-authors were among the very first to integrate a conventional macroeconomic model with the standard epidemiological model of virus transmission, the Susceptible-Infected-Recovered (SIR) model.[9]. This SIR-macro model was influential in several ways. First, it allowed researchers to study how the virus, economic policies and the aggregate economy interacted. As in real life, an increase in the virus' spread led to less spending and a decrease in employment. This reduction in economic activity had corresponding health benefits by limiting the spread of the virus. Furthermore, the model allowed policymakers to analyze the health and economic tradeoffs of various social distancing policies before issuing a policy change in the actual economy.

In our recent paper Stay-at-Home Orders in a Fiscal Union, we use this new economic data to estimate the impact of stay-at-home orders on consumer spending and employment. Then we extend the SIR-macro model to incorporate multiple locations. This allows us to address whether a national stay-at-home order is better than leaving states "a little bit of flexibility," as President Trump suggested.

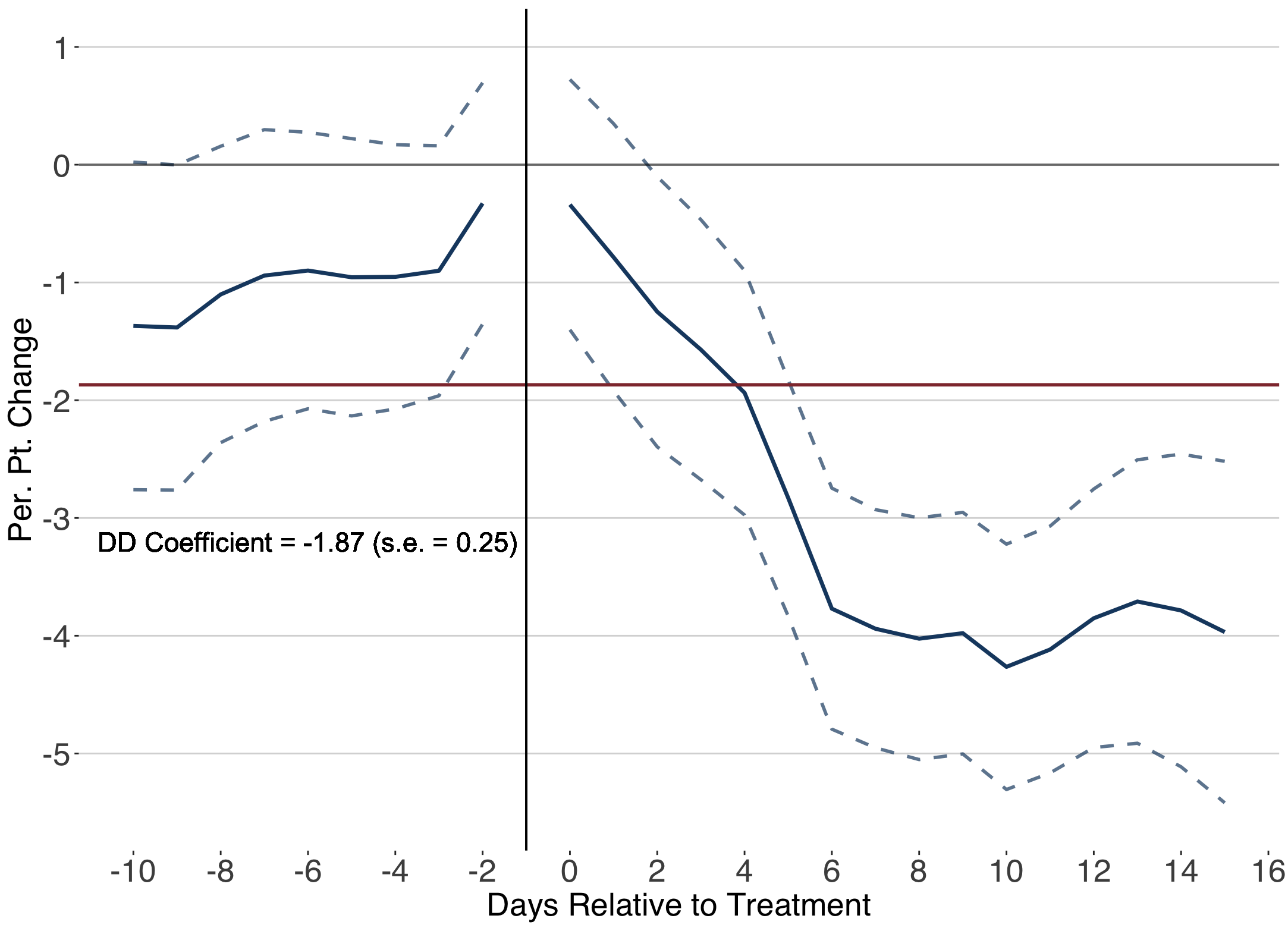

Figure 1 shows the impact of the initial stay-at-home orders issued by states in March and April of 2020. Not all states issued stay-at-home orders on the same day. Our analysis uses this difference in timing to estimate what the average effect of a stay-at-home order is x days after it is issued (e.g., the day of, one day after, . . ., 15 days after).

Panel (a) shows that hours worked decreased by an additional 4 percentage points, on average, in the states that issued them. Panel (b) shows a similar decline for consumer spending in the first several weeks after a stay-at-home order was issued. Overall, these results suggest that stay-at-home orders caused a cumulative impact of $15 billion in lost earnings and a $10 billion decrease in consumer spending in the span of half a month. Furthermore, the results suggest that stay-at-home orders caused almost 6 million people to temporarily lose their jobs, which accounts for 10 percent to 25 percent of the total employment loss during this period.

Were stay-at-home orders too severe or too lax? Although wider societal impacts of stay-at-home orders may prove difficult to calculate, our analysis shows that state and local orders did have real and significant effects on economic output, starkly illustrating the "health and wealth" tradeoffs of fighting the pandemic.

Throughout much of 2020, the Trump administration deferred decision-making regarding stay-at-home orders to the state and local level. While many have castigated the former president's team for relying too much on state decision-makers, our model tests whether a national stay-at-home mandate would have resulted in less economic impact or reduced infection spread.

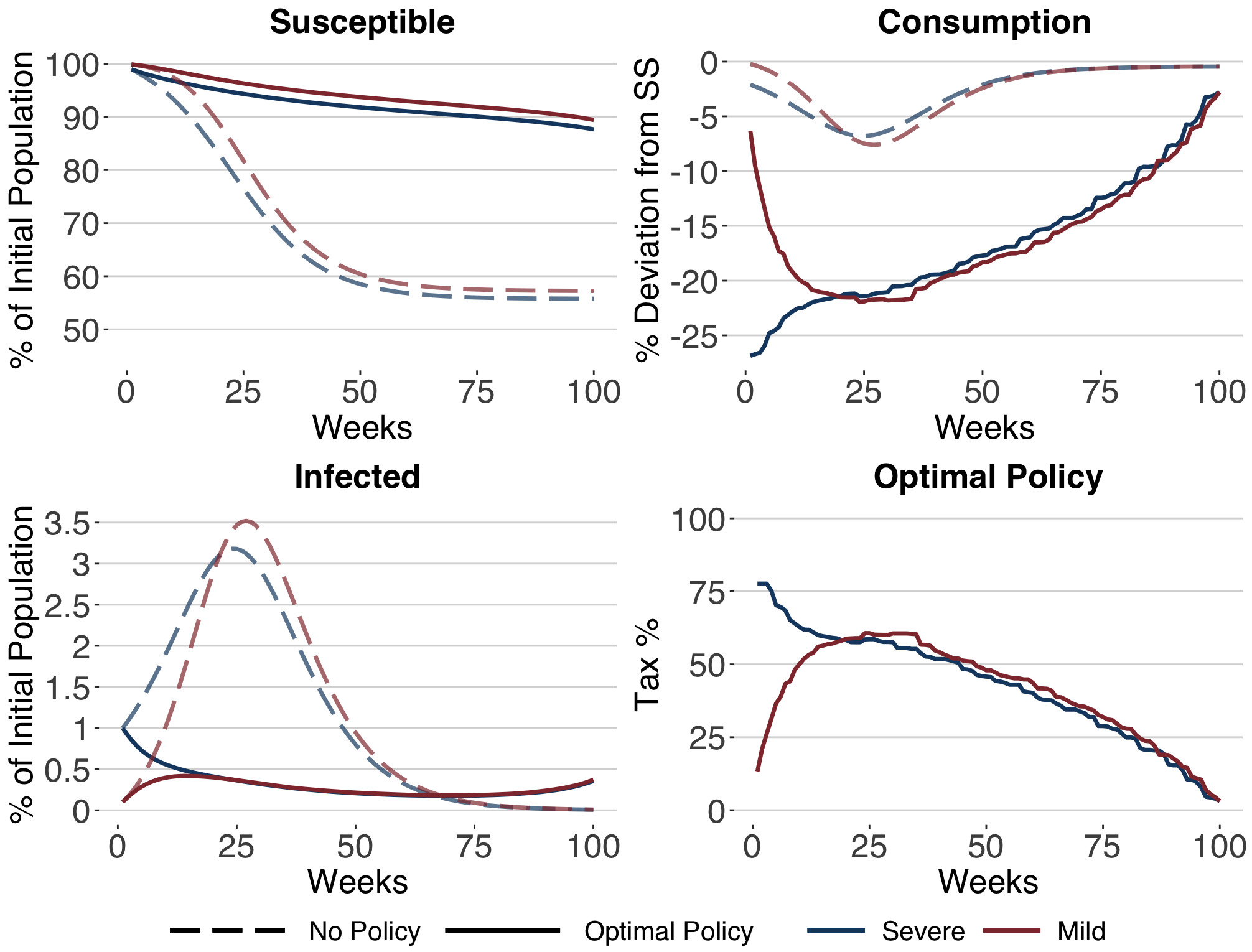

Figure 2 presents the implications of optimal mitigation policy in our model with solid lines and no policy with dashed lines. Although the model suggests that mitigation policy is necessary, it demonstrates the need for a state-by-state approach in policy flexibility. As illustrated by the bottom right panel in Figure 2, the state with a higher infection rate (blue line) initially sets a stricter policy than the state with a lower infection rate (red line). However, as infection rates converge, so do their policies. The state that starts with the lower infection rate, therefore, avoids an early dramatic economic shock, as demonstrated in the red line in the upper right panel in Figure 2.

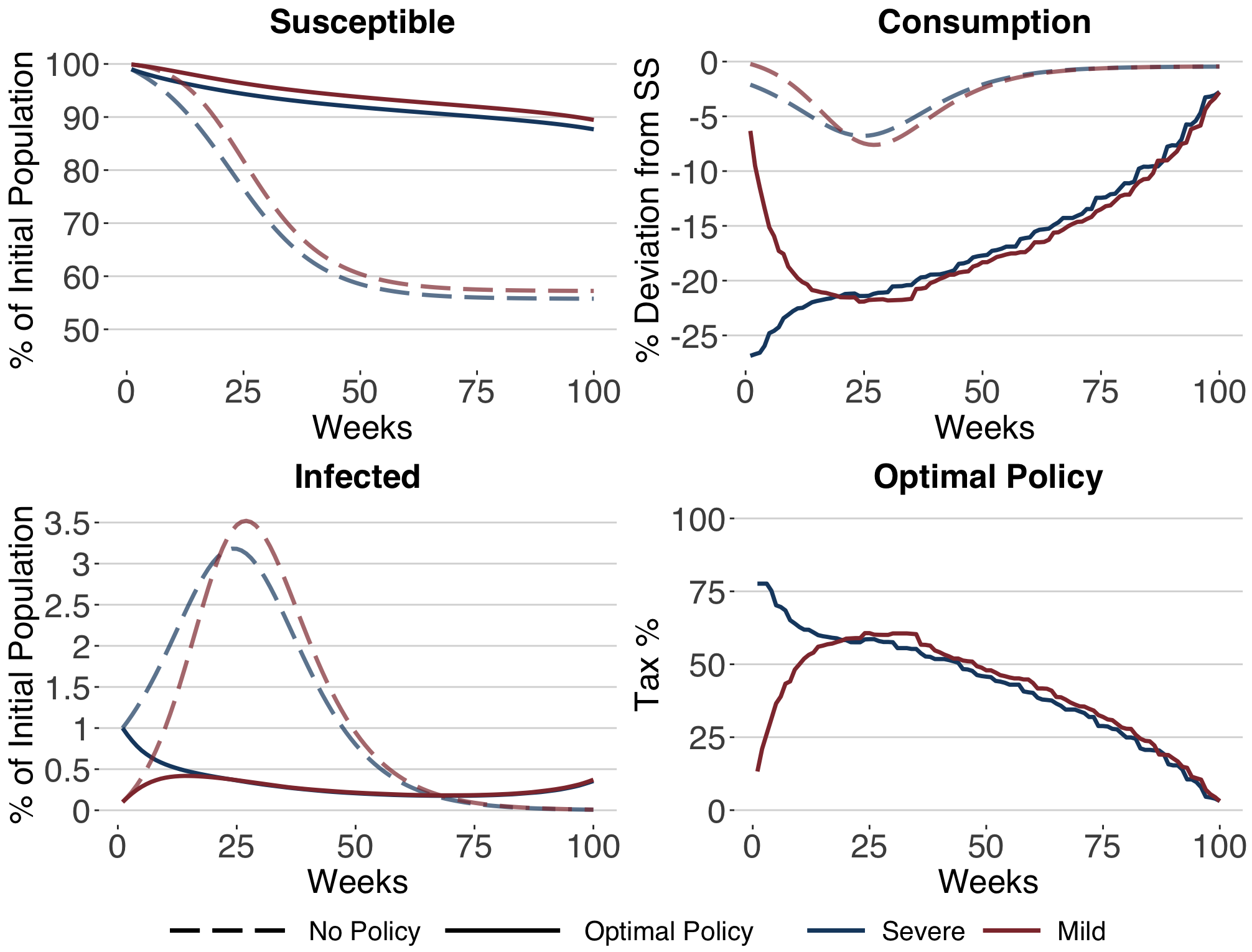

We next evaluated the impact of a national stay-at-home policy. As shown in Figure 3, the national policy did not have a material impact on the states' infection rates. However, under a national policy, the mildly infected state experiences significantly larger declines in consumption at the onset of the pandemic. Simply put, a nationwide mandate slows economic activity in a mildly infected state without the intended health benefits of reducing virus spread within that state.

Our results strongly suggest that issuing a national stay-at-home order at the onset of the pandemic when the virus was spreading primarily in a small group of cities may have imposed earlier and deeper economic costs on states with relatively low case numbers without any corresponding reduction in infection rates in such states. However, as the virus spread more uniformly across the country in the last several months of 2020, a nationwide order seemed more appropriate as infection rates across states started to converge.

The ongoing distribution and administration of the vaccine demonstrate the need for close cooperation between federal and state agencies. However, our analysis shows that informed state-level decision-making about stay-at-home orders is most effective in minimizing the economic costs required to achieve larger public health goals.

Further Reading:

- Chetty, Raj, John N. Friedman, Nathaniel Hendren, Michael Stepner and The Opportunity Insights Team, "How Did COVID-19 and Stabilization Policies Affect Spending and Employment? A New Real-Time Economic Tracker Based on Private Sector Data," NBER Working Paper No. 27431, 2020.

- Crucini, Mario and Oscar O'Flaherty, "Stay-at-Home Orders in a Fiscal Union," NBER Working Paper No. 28182, 2020.

- Eichenbaum, Martin, Sergio Rebelo, and Mathias Trabandt, "The Macroeconomics of Epidemics," NBER Working Paper No. 27141, 2020.

[1] CNBC (2020), Dr. Fauci slightly delays timeline for widespread vaccine availability in the U.S. to May.

[2] NBC News (2020), "'Fire Gruesome Newsom!': Stay-at-home protests in California and across the country,".

[3] Fox News (2020), " Coronavirus shutdown: What states have seen protests against stay-at-home orders,".

[4] NJ.com (2020), "'Open New Jersey now!' Protesters in Trenton demand Gov. Murphy lift coronavirus lockdowns despite rising death toll,".

[5] USA TODAY (2020), " Partisan divide over economy grows, but Americans more worried about their health: Exclusive poll,".

[6] The Economist/YouGov (2020), Poll: 59. National Stay-At-Home Order,.

[7] Press briefing (2020), "Remarks by President Trump, Vice President Pence, and Members of the Coronavirus Task Force in Press Briefing,".

[8] Politico (2020), " Fauci endorses national stay-at-home order: 'I just don't understand why we're not doing that',".

[9] Eichenbaum, Martin, Sergio Rebelo, and Mathias Trabandt, "The Macroeconomics of Epidemics," NBER Working Paper No. 27141, 2020.