SUMMARY

UNIFYING THEME: To Keep the Republic: Strengthening Democratic Principles at Home and Abroad

The poor response of the federal government during the current pandemic, including the public health agencies, illustrates the importance of an effective bureaucracy. Yet both parties have paid too little attention to government capacity. This short paper explains why Republicans and Democrats have underinvested in the departments and agencies of the federal government with focus on persistent myths about the bureaucracy.

by David E. Lewis, Rebecca Webb Wilson University Distinguished Professor of Political Science

In January of 2021, the number of COVID19 cases in the United States surged past 21.5 million and deaths approached 360,000 souls. Those digging deeply into the crisis gave different explanations for the nation's pitiful pandemic response. Some blamed poor presidential leadership. The president's critics charged him with missing clear warning signs, refusing to use in-house government expertise and plans, and undercutting efforts to curtail the virus's spread. For all the criticism of the president, other analysts puzzled over the poor performance by the bureaucracy responsible for pandemic response. At the heart of complaints about poor bureaucratic performance was the CDC. The New York Times publicly wondered "What Went Wrong?" in the agency whose entire purpose is to combat infectious diseases like COVID19. A deep dive into why the public health bureaucracy faltered reveals organizational chaos and resource problems.

Of course, both kinds of explanations can be true. For some, the president's choices in the moment prevented an effective response and his earlier choices to neglect and dismantle the instruments of governance had borne bitter fruit in a broken and demoralized public health bureaucracy. Others, however, suggest that problems in the public health bureaucracy and the administrative state preceded the Trump Presidency. Careful observers inside and outside of government have been raising alarm about the decaying infrastructure of government for some time. Cracks are beginning to show and these cracks reveal problems more deeply rooted than one presidential administration.

One thing this tragic crisis revealed is the importance of a functioning administrative state to do what voters have asked government to do-in this case protect them from threats they cannot manage themselves. In this brief paper, I explain why Republicans and Democrats have underinvested in the departments and agencies of the federal government. I focus on persistent myths about the bureaucracy held by voters and encouraged or parroted by elected officials. I use various sources of data I have collected to dispel these myths in order to clear away the underbrush that makes tackling needed reform difficult. I conclude by previewing some simple bipartisan reforms that can improve the performance of the government we share.

Republicans, Democrats and the Public Service

A reasonable model of the behavior of elected officials starts with the understanding that they pursue reelection. They have incentives to adopt views and take actions consistent with the opinion of voters. The specific content of these views and actions with regard to agencies like the CDC is informed by voters' views of the bureaucracy. The public does not know much about the federal government and the ways that bureaucracy operates is often obscure to voters. This does not create a strong motivation for elected officials to be particularly attentive.

The public's views are also shaped importantly by public reporting on the bureaucracy, which is largely negative. As a thought experiment, imagine if the Washington Post, Fox News, or the New York Times was filled with stories with the following headlines:

- "DOT policies lead to reduction in traffic fatalities"

- "Millions of Social Security checks arrive in mailboxes of needy seniors without incident"

- "Government agencies keep America's food supply clean and safe yet again"

- "Federal government ensures that the nation's ports safe and secure for years running"

Imagine the public's views if they were fed a diet of such stories on a daily basis. Of course, news outlets do not carry such stories. Those stories do attract viewers or readers. When there is news about the federal bureaucracy, it is relentlessly negative. Not surprisingly, the posture of elected officials reflects this fact. Elected officials secure support from voters by agreeing with negative stereotypes about government, supporting punitive legislation, taking credit for identifying faults, and proposing solutions to problems (thereby highlighting the problems).

While Republicans have long favored a smaller national government and a shortened reach of government programs and regulation, both Republicans and Democrats embraced a loose package of management ideas starting in the 1980s and continuing into the new century that emphasized better outputs at lower cost. The so-called New Public Management emphasized a customer focus, decentralization, market competition, cost controls, performance measurement and private sector management techniques. This package of ideas was attractive because it was consistent with the belief that bureaucracy was bloated, inefficient, and needed to be controlled. It provided a mechanism for slashing administrative costs while protecting programmatic spending. Its most prominent manifestation was probably President Clinton's National Performance Review and promise to "reinvent government." At the same time new breed of Republicans, starting with Ronald Reagan has also advocated some version of "starving the beast" or the "deconstruction of the administrative state." The consequences of such beliefs on the performance of a public health bureaucracy are not hard to see.

Myths of Federal Bureaucracy

Where do underlying beliefs about bloated bureaucracies, deep state resistance, and gross inefficiencies come from? In part, they come from experience. Like any large organization, whether it is the federal government or a local cable company, federal agencies can be bureaucratic--slow, unresponsive, and impenetrable. When organizations do not get to recoup the money they save (agencies do not), there are fewer incentives to operate efficiently. Yet, some opinions about the federal bureaucracy stem from confusion about what agencies do and how the government operates.

Bloated Bureaucracy

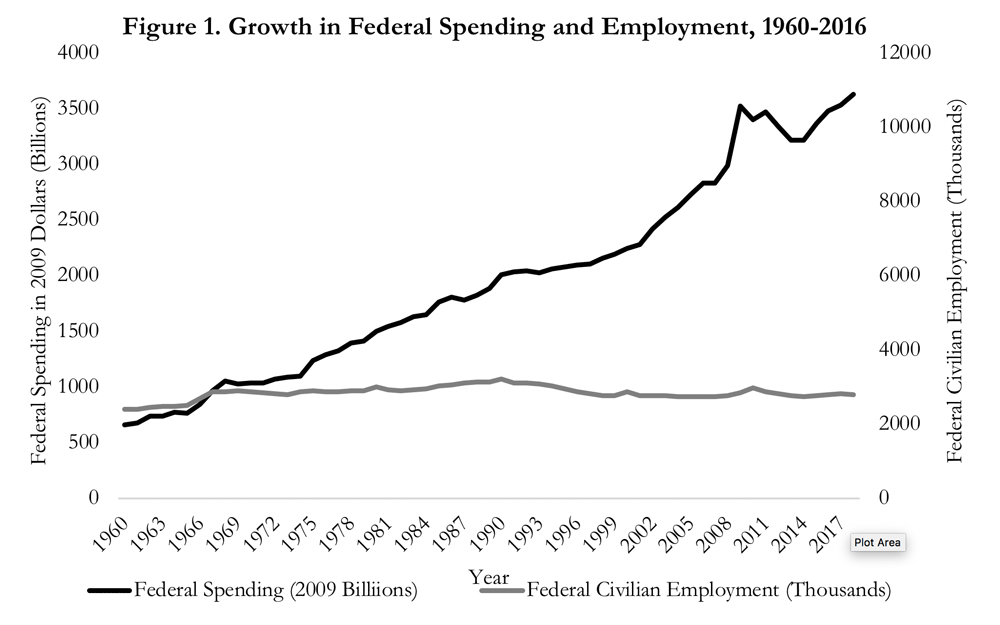

When people think about the federal government, they envision an ever-expanding set of government agencies filled with Washington, DC bureaucrats. A natural target for budget cutters is the federal workforce. This common view of the federal workforce is importantly misguided. Look at Figure 1 to see why. The figure includes data from 1960 to 2018 on inflation-adjusted federal spending and the size of the federal civilian workforce. Federal spending has increased more than 500% since 1960 while the federal workforce is only 17% larger. During the intervening period, the national government has taken on new expansive new responsibilities in civil rights, Medicare, the environment, safe workplaces, consumer protection, education, and homeland security. Government is doing more than ever before with a workforce not much larger than it was in 1960.

Note: Federal spending data come from Office of Management and Budget, Historical Tables, Table 1.1; Employment data come from Bureau of Labor Statistics, Federal Government, Including U.S. Postal Service. Federal spending is an estimate from the historical table. BLS employment data for 2018 is an average, excluding December.

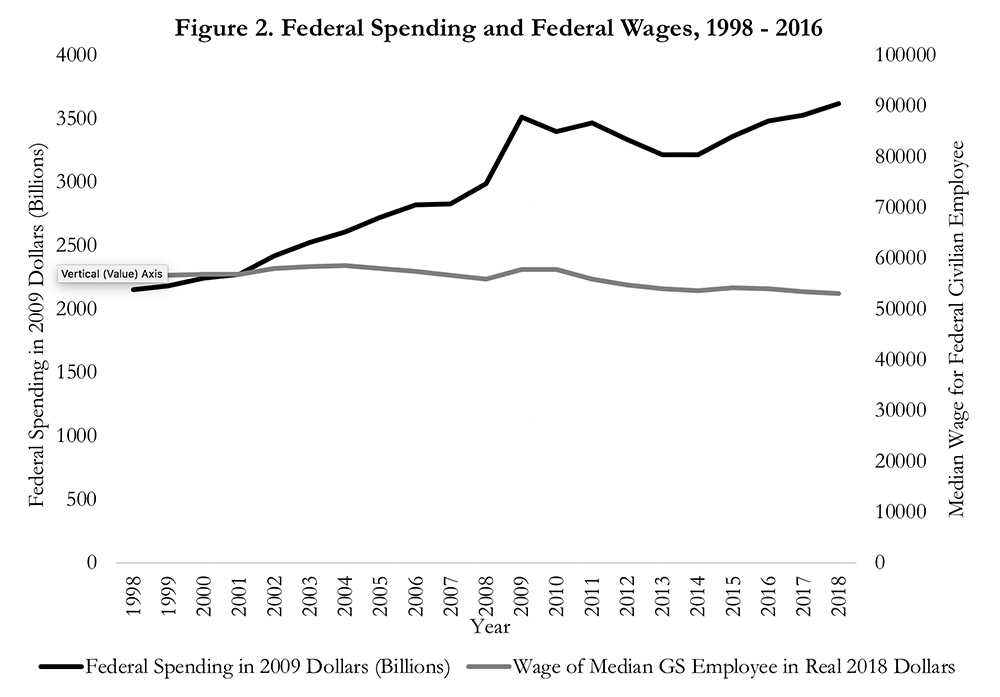

It should also be noted that only 15% of these federal employees work in the Washington, DC metropolitan area. The vast majority of federal employees work in other parts of the country or the world. They are our neighbors, the park rangers, air traffic controllers, and FBI agents that do the work we have asked them to do. They have been the target of regular pay freezes and the victims when Congress and the president cannot agree on a budget and the government shuts down. Figure 2 includes overall spending data alongside the median federal employee's income (in 2018 dollars). Spending follows the familiar pattern from Figure 1 but real wages for federal employees are actually going down. Like income for persons working in other sectors during this period, federal workers earn lower salaries now than they did 20 years ago even though government work is growing in volume and complexity and the work is increasingly managerial, professional and technical.

Note: Wages are first step of median federal employee GS grade during this time period. Source for median grade, 1998-2018: www.fedscope.opm.gov. Source for Step 1 salaries: https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/pay-leave/salaries-wages/.

"Deep State" Resistance

President Donald Trump's supporters blamed many of his administration's difficulties on recalcitrant bureaucrats. Is there such a thing as a deep state, a coterie of left-leaning bureaucrats that have significantly resisted the policy initiatives of President Trump? In a 2014 survey of federal executives I conducted with Georgetown Professor Mark Richardson, 44% of respondents identified as liberal, 35% as moderate, and 21% as conservative. This raises the natural question of whether civil servants, particularly liberal civil servants would work with a president they disagree with.

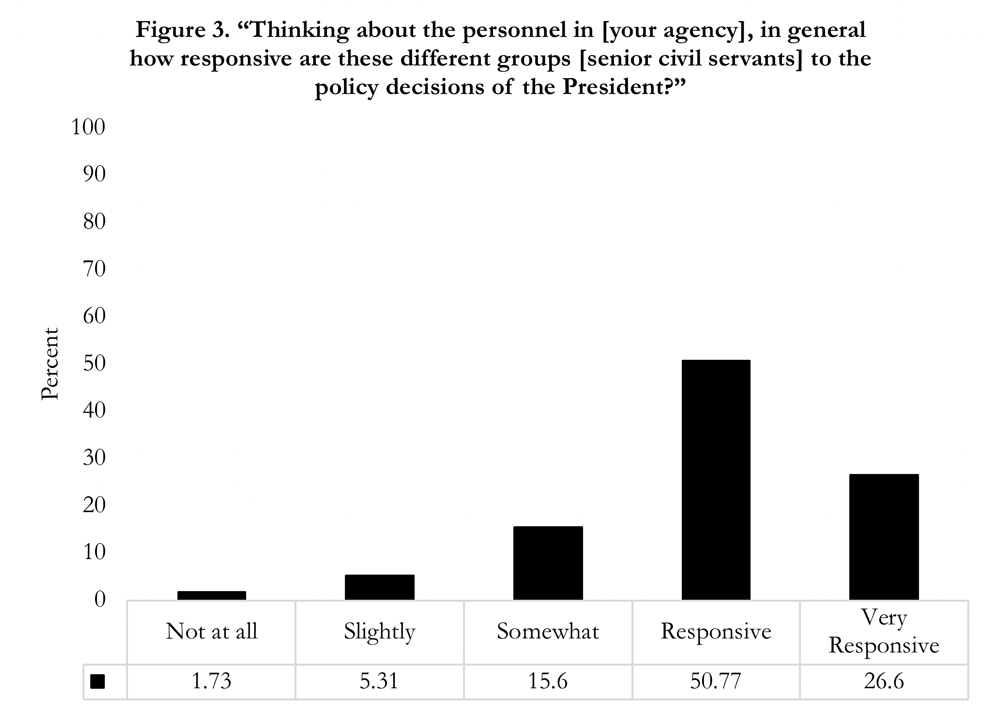

There is no easily available data yet from the Trump Administration but we do have some data from the Obama Administration. Notably, Richardson and I asked respondents, "Thinking about the personnel in [your agency], in general how responsive are these different groups to the policy decisions of the President?" We report their responses in Figure 3.

Source: 2014 Survey on the Future of Government Service (https://www.vanderbilt.edu/csdi/research/sfgs.php).

Both Democratic and Republican respondents report that senior civil servants are relatively responsive. Seventy-seven percent report that senior civil servants in their agency are responsive or very responsive to the president. This is a reasonably high number given that some agencies are designed to be unresponsive to the president (e.g., Internal Revenue Service, Federal Reserve) and agencies are also constitutionally obligated to be responsive to the law, Congress, and courts. In other words, it is unclear constitutionally how responsive agencies should be to the president.

When we disaggregate the data into the most liberal and most conservative agencies, some differences emerge but even in the places where we should expect the most resistance, the percentages are quite high. In the most liberal agencies (e.g., Department of Labor, Department of Education) close to 82% report that senior civil servants are responsive or very responsive to the president. In the most conservative agencies (e.g., Department of Defense), 74% report that senior civil servants are responsive or very responsive to the president. In the Obama Administration, the vast majority of government executives report that senior civil servants were responsive to the president.

So, was there a vast "deep state" conspiracy? Based upon what we know about the top levels of the civil service from that last administration, it is unlikely. Were there pockets of resistance to President Trump in some agencies? Probably. This is the case for all new presidents, Republican or Democrat, and it is due to both statutory responsibilities and the views of civil servants themselves.

Private Sector Superiority

One common refrain repeated by elected officials and voters is that they wish government would run more like a business. There are obvious differences between the public and private sectors, namely that we hold the public sector to higher standard than the private sector. Public sector managers, unlike most of their private sector counterparts, have rules related to buying American products, open contracting processes to limit sweetheart deals, equal treatment, veterans preference in hiring, and so forth. A lot of the restrictions on government activity come from our good intentions and as a result the context of management is quite different.

Presumably, voters longing for a government that operates like a business are not referring to the high percentage of businesses that fail. They probably also are not referring to doctors that make them linger in waiting rooms, private bill collectors, or local cable companies. Some private sector firms are arguably less responsive than government agencies. Still, we understand the sentiment that voters want high value for little money, professionalism, and good treatment. How do government agencies compare to large private sector firms?

In 2020 Mark Richardson and I fielded a survey of thousands of federal executives, asking these executives some of the same questions about their agencies that Mercer Sirota asked comparable private sector executives about their companies. In Table 1, I include a comparison of responses. A few features stand out. First, there are a number of areas where the public and private sectors are more or less comparable-innovation, work climate, management, and tools. Executives in both sectors report that their organization supports the development of new ideas. Two thirds report support for innovation. Three-quarters in each sector report that their organizations are a good place to work and that they have the right tools to do their jobs properly. In general, their views about the quality of management in the organization is the same. About 3 out of 5 in each report that there is a climate of trust in their organization and their organization is an "effectively managed, well-run organization."

Table 1. Comparison of Public and Private Sector Organizational Performance, 2020

| Question | %Agree (Government) | %Agree (US Private Sector) | Difference |

| We have enough employees where I work to do a quality job. | 45 | 58 | -13 |

| Promotions in my workgroup are based on a person's ability | 64 | 53 | 11 |

| At my agency/company we deal effectively with poor performers. | 24 | 47 | -23 |

| The work environment at my agency/company supports development of new and innovative ideas. | 69 | 66 | 3 |

| I would recommend my agency/company as a place to work. | 79 | 76 | 3 |

| My agency/company is an effectively managed, well-run organization. | 58 | 60 | -2 |

| There is a climate of trust within my agency/company. | 58 | 57 | 1 |

| I feel I have the right tools and resources (equipment, parts, supplies, hardware, software, etc.) to do my job properly. | 73 | 73 | 0 |

| My agency/company has a sense of urgency for getting things done. | 80 | 57 | 23 |

| My agency/company is investing now to enable our future success. | 58 | 69 | -11 |

| My work group makes decisions based on data. | 61 | 72 | -11 |

Source: Survey on the Future of Government Service, 2020 (sfgs.princeton.edu). Private sector data provided by Mercer-Sirota.

Government organizations come out better on a few dimensions. Notably, federal executives are more likely to report that promotions are based upon a person's ability with 64% agreeing with that statement, compared to 53 percent in the private sector. Surprisingly, 80 percent of federal executives report that "My agency has a sense of urgency for getting things done" compared to only 57 percent for private sector executives. It is hard to tell how much of this difference is due to the unique context of the pandemic but the difference is striking and contrary to what one might expect.

Where the private sector has a notable advantage is in the size of the workforce, the ability of managers to deal with poor performers, the use of data and long-term planning. Fewer than half of government executives report having enough employees where they work to do a quality job compared to 58 percent among private sector executives. This should be no surprise given the data we examined above. The largest gap between the public and private sector is in dealing with poor performers. There is a 23-percentage point gap, with private sector executives much more likely to report that "At my company we deal effectively with poor performers." It is notable, however, that even in the private sector less than half of executives agree with this statement. Private sector executives also report greater use of data and greater attention to long term planning in their organizations Federal executives operate in an uncertain and political budget environment, subject to continuing resolutions and regular shutdowns. This makes planning difficult. The federal government is also lagging behind in the collection and use of data in decision making.

Overall, the research does not support the general claim that the private sector is better or more efficient than the public sector. In fact, some of the differences between the sectors, particularly those related to the number of employees, the ease or difficulty of dealing with poor performers, and the presence of long-term planning have less to do with bureaucrats than the rules imposed and decisions made by the elected officials that supervise them. Federal executives report a greater sense of urgency and a general enthusiasm for their organization and the work they do.

Bipartisan Reform

Providing data to help dispel some common myths about the federal bureaucracy is not to suggest that there are no problems in the bureaucracy. On the contrary, given the beliefs of voters and their elected officials about the bureaucracy, it would be surprising if the departments and agencies of government were well supported and problem-free. Dispelling myths, however, is an important first step in doing the important work of administrative reform. The poor response of the CDC to the largest public health crisis in a generation illustrates the importance of this task. And, we can find other examples, including the poor performance of the Capitol Police in response to violent protesters and the apparent multi-agency failure which allowed a catastrophic Russian hack into the federal government's information technology apparatus. Republicans and Democrats may disagree about the proper scope of government, but they should agree on proper functioning of the government they have created. Necessary steps include reducing the number of politically appointed positions and improved efforts to recruit, develop, and retain a competent federal workforce, efforts I will lay out more fully in papers to come.

Further Reading:

- John J. DiIulio. 2014. Bring Back the Bureaucrats. West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Press.

- David E. Lewis, "'Deep State' Claims and Professional Government," The Regulatory Review, December 5, 2017.

- David E. Lewis. 2019. "Deconstructing the Administrative State," Journal of Politics, 81(3):767-89.

- David E. Lewis, "How to Solve the Vacancies problem that looms over federal government," The Hill, June 4, 2020.

- David E. Lewis. N.d. "Is the Failed Pandemic Response a Symptom of a Diseased Administrative State?" Daedalus, forthcoming.

- Lewis, Michael. 2018. The Fifth Risk. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.

- Light, Paul C. 2008. A Government Ill Executed: The Decline of the Federal Service and How to Reverse It. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Paul R Verkuil. 2017. Valuing Bureaucracy: The Case for Professional Government. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

[1] Eric Lipton, Abby Goodnough, Michael D. Shear, Megan Twohey, Apoorva Mandavilli, Sheri Fink and Mark Walker, "The C.D.C. Waited 'Its Entire Existence for this Moment.' What Went Wrong," New York Times, June 3, 2020 (https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/03/us/cdc-coronavirus.html); Caroline Chen, Marshall Allen and Lexi Churchill, "Internal Emails Show How Chaos at the CDC Slowed the Early Response to Coronavirus," ProPublica, March 26, 2020 (https://www.propublica.org/article/internal-emails-show-how-chaos-at-the-cdc-slowed-the-early-response-to-coronavirus, accessed July 27, 2020).

[2] See, e.g., John J. DiIulio, Bring Back the Bureaucrats. West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Press (2014); Francis Fukuyama, Political Order and Political Decay. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux (2014) 2014; Paul C. Light, A Government Ill Executed: The Decline of the Federal Service and How to Reverse It. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press (2008); Paul R. Verkuil, Valuing Bureaucracy: The Case for Professional Government. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press (2017).

[3] See Charles T. Goodsell, The New Case for Bureaucracy. Rev. 5th ed. Washington, DC: CQ Press (2015) and Susan Webb Yackee and David Lowery, "Understanding Public Support for the US Federal Bureaucracy," Public Management Review 7(4):515-36 (2005). See also Lisa Rein and Ed O'Keefe, "New Post poll finds negativity toward federal workers," Washington Post, October 18, 2010 (http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/10/17/AR2010101703866.html , accessed January 8, 2019). The public's views of the bureaucracy are nuanced, however. Their views of specific agencies can be positive even if their general perceptions of the executive bureaucracy are quite negative. See Goodsell The New Case for Bureaucracy and Verkuil Valuing Bureaucracy.

[4] See Christopher Hood, "A Public Management for All Season?" Public Administration 69(1):3-19 (1991).

[5] Al Gore, From Red Tape to Results: Creating a Government That Works Better & Costs Less. Report of the National Performance Review. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office (1993).

[6] This discussion comes more or less directly from David E. Lewis, "Deconstructing the Administrative State," Journal of Politics, 81(3):767-89 (2019).

[7] It replicates and updates a similar figure in DiIulio, Bring Back the Bureaucrats.

[8] Specifically, I calculated the median GS grade, selected the first step in this grade, and adjusted for inflation to put this amount in 2018 dollars.

[9] This section borrows heavily from David E. Lewis, "'Deep State' Claims and Professional Government," The Regulatory Review, December 5, 2017.

[10] Some articles detailing these claims include Alan Abramson, "President Trump's Allies Keep Talking About the 'Deep State.' What's That?" Time Magazine, March 8, 2017 and Devin Henry, "Federal employees step up defiance of Trump," The Hill, August 5, 2017.