Vanderbilt researchers explore new science education approach to build youths’ agency amid climate anxiety

By Jenna Somers

A three-year, nearly $1.3 million grant from the National Science Foundation supports a trans-institutional research team at Vanderbilt University investigating an innovative approach to STEM education that could help young people develop STEM identities and agency amidst climate anxiety.

Children around the world experience growing levels of climate anxiety as they witness the worsening effects of climate change and governments’ inadequate responses to improve future conditions; moreover, they feel powerless to do anything themselves.

To understand how to support youth experiencing climate anxiety, Heidi Carlone, professor of teaching and learning and the Katherine Johnson Chair in Science Education, is leading a team of researchers from Peabody College of education and human development, the College of Arts and Science, and the School of Medicine Basic Sciences to investigate the potential of place-based learning and digital storytelling to nurture middle school youths’ sense of personal agency, STEM career knowledge and affiliation, and STEM identity play.

“Identity play involves exploring different aspects of oneself in creative and playful ways. The project provides youth with unique opportunities to step into new roles. They’ll engage in outdoor activities, delve into STEM, and interact with the natural world, scientists, and the public in ways that may differ from how they see themselves, or how others typically see them,” Carlone said.

The research team is collaborating with community partners, such as the Mill Creek Watershed Association, Cumberland River Compact, Tennessee Nature Academy, Unearthing Joy, and Conexión Américas, members of which serve on the project’s advisory boards. They also are working with Antioch Middle School, Valor Collegiate Academy, and the Day of Discovery Program, a partnership between the Vanderbilt Collaborative for STEM Education and Outreach and Metro Nashville Public Schools.

Place-based learning

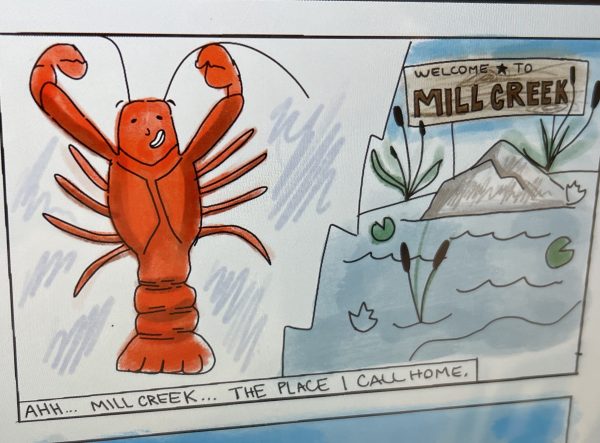

Carlone and her team are engaging Nashville middle school students in environmental science fieldwork and restoration of Mill Creek, a watershed that flows 28 miles through one of the most diverse zip codes in Tennessee, from Nolensville to the Cumberland River near Shelby Bottoms. Carlone has dubbed the project T-ReCS (Teens Re-Storying the Creek with STEM).

“Mill Creek is a rich context for youth who live in the community to learn about the complexities of nature and cultural relations, the potential of science, engineering, and technology in exacerbating and mitigating climate disasters, and the disproportionate effects of climate events on vulnerable human and more-than-human populations,” Carlone said.

The Mill Creek streamside environment is the exclusive home to the federally endangered Nashville crayfish and supports more than 240 additional at-risk species. According to Kathleen Dennis, director of the Mill Creek Watershed Association and an advisor to T-ReCs, development around Mill Creek has impaired its ecosystem through sedimentation, stream erosion, elevated pathogens and, in several areas, low oxygen levels. Multiple floods have destroyed homes and polluted the creek. In 2021, a flood swept abundant amounts of plastic litter from a restaurant supply company’s storage facility into the creek.

Lily Claiborne, assistant professor of the practice of earth and environmental sciences, and Chris Vanags, director of the Peabody Research Office and research assistant professor of earth and environmental sciences, are co-investigators on T-ReCS, advising the middle school students on their scientific fieldwork and helping them understand Mill Creek’s ecological history and challenges. They also plan to connect the middle school students with Vanderbilt STEM students who have conducted research projects at Mill Creek and can serve as mentors.

“Through their fieldwork at Mill Creek, I hope students develop an understanding of how dynamic ecosystems are and how easily they are affected by environmental problems, pollution, and development, but also that they can rebound rapidly,” Claiborne said. “We call places like Mill Creek ‘systems’ because critters are connected to the water, which is connected to the sediment, which is connected to the weather. A change in any one of those affects all the others.”

Claiborne lives in a historically neglected and under-resourced neighborhood near Mill Creek. When the plastic spill occurred, she recognized it as an immediate environmental disaster and organized teams of students and faculty members who work on water-related issues to collaborate on research projects measuring the effects of pollution in the ecosystem.

“…critters are connected to the water, which is connected to the sediment, which is connected to the weather. A change in any one of those affects all the others.”

Having collaborated extensively with Nashville environmental organizations, Vanags connected the T-ReCS team with several community partners.

“I want students to understand the cumulative impacts on local watersheds—and even what a watershed is,” Vanags said. “A lot of people don’t think about how collectively we contribute to water quality. Even if you’re away from a stream, anything you do in that whole watershed impacts the waterway.”

Vanags plans to introduce the middle school students to the work of Sarah Habeck, BS’22, who performed the Environmental Protection Agency’s rapid bio assessment protocol for her honors thesis on Mill Creek. “This protocol is great because it’s a very accessible assay, just like the canary in the coal mine,” Vanags said. “You can look at the assemblage of macro-invertebrates within a creek and categorize them based on how sensitive they are to pollution and then create an index that shows how the macro-invertebrate assemblage reflects water quality. So, the more sensitive organisms present in a stream, the higher the water quality is.”

Kenn Cabrera, Madonna Decena, and Parvin Atroshi, three Fulbright DAI Fellows in the Department of Teaching and Learning, also are a part of the project team. Atroshi is from Uganda. Cabrera and Decena are both from the Philippines and have worked with students in their home country to care for and learn from local environments. At Mill Creek, the Fulbright Fellows and Vanags taught students at the water chemistry station, and they also have mentored students in their fieldwork and storytelling projects.

In addition to the environmental concerns, the middle school students are exploring Mill Creek’s connections to Indigenous people’s history. Dennis introduced Carlone and the middle school students to members of Indigenous groups in Nashville. They taught the students that when the Trail of Tears passed through the Nashville area, forcibly displaced members of the Cherokee Nation were required to camp near Mill Creek because they were not allowed to enter Nashville. In their digital stories, the students may weave together Indigenous people’s history and details from the more recent environmental effects on the creek.

Digital storytelling

Based on their fieldwork and restoration projects, students will create digital stories about Mill Creek’s ecological, historical, and social significance in the form of podcasts, augmented reality, and “zines” (short for magazines), a pamphlet-like publication that tells stories from unique or marginalized voices.

“Digital storytelling is a way for youth to recapture a sense of agency amidst considerable climate anxiety and encourages multiple ways of knowing and educating others about a complex socioecological system. The students’ stories of Mill Creek will exist in relational tensions—of devastation and hope, of loss and restoration—and will serve as models for the transformative, boundary-spanning potential of a technology and field science pairing,” Carlone said.

Jad Abumrad, distinguished research professor of communication of science and technology and of cinema and media arts, will consult with students on designing podcasts to tell powerful stories about the creek, focusing on aspects such as writing, voice, and technical production.

“Teaming up with young Nashvillians to tell their stories and express their creativity is one of the most exciting parts about joining Vanderbilt,” Abumrad said. “I am looking forward to working with Heidi and the team she’s leading and to sharing stories about Mill Creek that speak volumes about our place in the world.”

Kendra Oliver, associate professor of pharmacology and director of design at the School of Medicine Basic Sciences, and Hannah Ziegler, doctoral student in the Department of Teaching and Learning, plan to support students interested in creating stories with augmented reality (AR). According to Oliver, AR connects digital elements to physical places or objects and can therefore create experiences with various actors and histories that can be leveraged for place-based learning. Oliver and Ziegler are exploring ways to guide middle school students through the highly creative and technical process of designing AR.

“This is a fascinating opportunity to reflect with Hannah and others about the creative underpinning of AR production and how it can be used to tell unique stories, particularly stories of Mill Creek as interpreted by middle school students,” Oliver said.

Additionally, Blaine Smith and Liwei Zhang, associate professor of the practice and doctoral student, respectively, in the Department of Teaching and Learning, are collaborating on developing the “zines” curriculum. It was originally conceived of by Jenneh Kamara, MEd’22, who passed away this summer. For the team, her legacy and commitment to empowering student voices lives on through this project.

Other collaborators include Tessaly Jen, a doctoral student in the Department of Teaching and Learning, who helped design field science and critical geography curriculum; Jingyi Chen, MEd’23, who is creating an interactive website of historical stories of Mill Creek that illustrate devastation and community thriving; and Yelena Janumyan, PhD’05, and Zachary Conley, instructors at Day of Discovery and postdoctoral researchers working on the project’s design and research team.

Identity play

Building on current identity studies’ literature, Carlone seeks to create and refine a grounded theory of identity play throughout the T-ReCs project by emphasizing youths’ agency, imagination, and playful renderings of the future. She wants education to promote an understanding of science among young people that is expansive and that sees science as a tool for studying the symbiotic relationship between community thriving and ecological thriving.

“We anticipate that these horizon-expanding experiences will enable youth to broaden their understanding of themselves, as creative and brilliant individuals capable of communicating important insights about the geology, ecology, and social and cultural history of Mill Creek in ways that only youth can,” Carlone said.

To Carlone, traditional science education promotes a limited view of science, focusing mainly on established knowledge. She believes this approach not only fails to appeal to a diverse range of students, particularly those from minoritized backgrounds, but also inaccurately represents the nature of scientific work. Science is replete with creativity, iterative processes, and the exploration of new, sometimes unexpected paths in both personal and professional realms.

With this perspective, Carlone and her team provide youth with opportunities to engage with science in ways that more closely mirror authentic scientific identity practices, reflecting the dynamic and creative nature of scientific and identity exploration. At the same time, digital storytelling puts a youth-centric spin on science, enabling young people to experiment with different ways to communicate about and make an impact with the science they’re learning.

Importantly, identity play allows youth to see themselves as legitimate contributors to improving their communities and the environment. In a time of widespread climate hopelessness, acting on behalf of a single watershed may hold the key for future action on behalf of much wider systems.