Dinosaur Rainbow Monarchs

March 25, 2000: Sometimes an experience throws us off balance, and we are forced to view life from a new perspective—upside down, or from the ground. I got the phone call late at work. Somehow, I knew what I was about to hear. My parents had been divorced for two years, and the fact that they were both on the line when I answered supported my fears. My sister died. Hypothesis confirmed. After receiving the news, I hung up the receiver and diligently cleaned the tables at Mike’s Smokehouse (Eau Claire, Wisconsin) until they gleamed. I had anticipated this day, but I wasn’t ready for it; I needed more time to prepare for this. I collected myself, closed the restaurant, and went back to my efficiency college apartment to wait for my brother to arrive. I drove home with my brother, “the Kid,” to be with my mourning family and plan the funeral. The Kid is my best friend, and when we are together, we engage in epic conversations, but this three-hour drive home was unusually silent. As I gazed out of the passenger window, I noticed how dark it was that night—and then I saw a shooting star blaze across the skyline.

March 25, 2000: Sometimes an experience throws us off balance, and we are forced to view life from a new perspective—upside down, or from the ground. I got the phone call late at work. Somehow, I knew what I was about to hear. My parents had been divorced for two years, and the fact that they were both on the line when I answered supported my fears. My sister died. Hypothesis confirmed. After receiving the news, I hung up the receiver and diligently cleaned the tables at Mike’s Smokehouse (Eau Claire, Wisconsin) until they gleamed. I had anticipated this day, but I wasn’t ready for it; I needed more time to prepare for this. I collected myself, closed the restaurant, and went back to my efficiency college apartment to wait for my brother to arrive. I drove home with my brother, “the Kid,” to be with my mourning family and plan the funeral. The Kid is my best friend, and when we are together, we engage in epic conversations, but this three-hour drive home was unusually silent. As I gazed out of the passenger window, I noticed how dark it was that night—and then I saw a shooting star blaze across the skyline.

In the years that followed, March 25th became an annual day of reflection for me. As a way to cope with my pain, I started a ritual in honor of the Anniversary. Every March 25th, I pulled out her pictures, letters, and drawings. I composed a soundtrack to my grief as I re-played memories of her in my mind. The evening would begin after work. I set the scene: I lit candles, retrieved photo albums, and played “her” music—The Cure, Soundtracks from “City of Angels” and “The Crow,” Pretenders, Jars of Clay. I made sure my computer was online so that I could easily access any video that might remind me of her. Then I settled in for a ride on my emotional roller coaster. For several years after Britt died, March 25th became a personal commemorative “holiday” for me in honor of my sister. It was one day on which I allowed myself to let my guard down and release all of my pain. In the privacy and safety of my little apartment, I cried, yelled, laughed, and sobbed as much as I needed to without having to apologize. March 25th—a yearly purging of emotional vomit. After several years, I thought it would be helpful to begin to journal my annual healing lessons to document my therapeutic process.

March 25, 2007: I listened to “Radios in Heaven” by Plain White T’s. The lyrics: “Your time has already come, and I don’t know why/ Seems like just yesterday I was laughing with you/ Do they have radios in heaven? I hope they do/ ‘Cause they’re playing my song on the radio, and I’m singing it to you.” I dedicated this to my sister as I allowed myself to sink into the remembrance ritual for her.

I listened to and watched the video for “Untitled (How Could This Happen to Me)” by Simple Plan. The video depicted a family of five that was affected by the death of the youngest girl. She died in a car accident, and the “butterfly effect” (how one event can create ripples a world away) is what struck me while I watched this. In the video, it was raining, and a drunk driver collided with the youngest girl’s car. At home, her family was physically thrown against the wall at the moment of the collision—even though they did not yet know about her death. Figuratively, my sister’s death threw me against the wall and crashed me into the ground, and I reeled from the fallout in the rain of my tears.

March 25, 2008: I marked the 8th year without my sister. I listened to and watched the video “I Will Follow You into the Dark” by Death Cab for Cutie. The lyrics, “If there’s no one beside you when your soul embarks/Then I’ll follow you into the dark…” resonated. I plugged her name into Google and stumbled upon the transcript from The Middlewesterner—“The ABCs of Poetry: an Interview with Karl Elder.” Karl Elder is a professor and award-winning poet. What I read shook me:

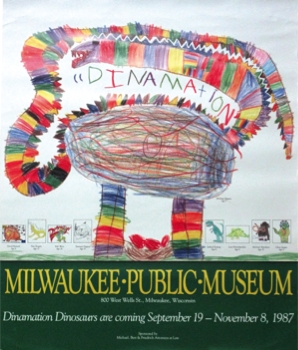

Among the stimulating works of art I’ve known in my life is a multi-colored, crayon drawing that won a poster contest for an exhibition called Dinamation at the Milwaukee County Museum, a five-year-old’s rendition of ‘dinosaur’ [Brittany Baganz, 1987]. It’s obvious that the child strayed outside of her lines; it has that look. But by God, Marc Chagall never made a creature more beautiful than that child’s.

Among the stimulating works of art I’ve known in my life is a multi-colored, crayon drawing that won a poster contest for an exhibition called Dinamation at the Milwaukee County Museum, a five-year-old’s rendition of ‘dinosaur’ [Brittany Baganz, 1987]. It’s obvious that the child strayed outside of her lines; it has that look. But by God, Marc Chagall never made a creature more beautiful than that child’s.

Time stopped. Dr. Elder was speaking of my sister…and comparing her to Marc Chagall (whom I hold in the artistic ranks of Picasso)! I remember how the Kid and I laughed at her creature with rainbow-colored flesh that bore no resemblance to Diplodocus. Brittany won the contest, and her Rainbodragosaurus was printed on thousands of posters and t-shirts to promote the new Dinamation exhibit (robotic, life-sized dinosaurs) at the Milwaukee Public Museum. In child terms, my sister had become famous, and won the ultimate jackpot (a cornucopia of dinosaur egg jawbreakers, gummies, and chocolates). It seemed her winnings continued into her afterlife; she had captured the respect of an esteemed poet and been compared to one of the most renowned painters of the 20th Century. One drawing, one creation made my sister a famous artist, and my heart ached at the thought that she never knew how she had enriched the lives of others with her color.

In the five years that followed the birth of the magical Technicolor beast in 1987, Brittany’s color slowly faded. She spiraled into despair and sickness. She dressed only in black, became addicted to drugs and alcohol, and carved scars into her skin. She was given a myriad of diagnoses by psychiatrists, including Borderline Personality Disorder, Major Depressive Disorder, Bipolar Disorder, and Addiction. Throughout my high school and college years, my family and I visited her in numerous institutions where we hoped she would be provided with help for her mental illnesses. My whole family traveled with her along her corkscrew path, and those years were excruciatingly painful because it seemed there was nothing we could do to help her escape her daily misery. My sister descended into darkness, and I wanted to follow her, and bring her back.

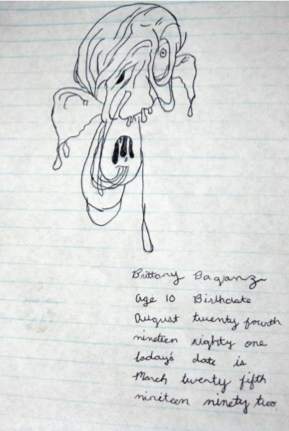

March 25, 2009: It was the 9th anniversary of my sister’s death. I was pulled back again and memories of my sister came rushing in. Among them was another drawing created by my sister the artist. A person’s face was depicted in pencil—gray. There were no rainbows. It reminded me of the character whose face melted off in “Raiders of the Lost Ark” (as a kid, I was too terrified to watch this scene). The sketch was tortured, gruesome. The artist’s signature at the bottom was familiar: “Brittany Baganz. Age 10… Today’s date is March twenty fifth, nineteen ninety two.” Again, time stopped. Exactly eight years after the melting face was sketched, the illness that shrouded my sister in gray and hid her color stole her entirely from the lives of those who love her. Brittany died on March 25, 2000—alone in a seedy hotel room in Orlando, Florida. She attempted to ease the pain of her illness with heroin, and it killed her. The “friends” that enabled her ran away when she showed signs of trouble. My sister died all alone. If only I had been there, she wouldn’t have been all alone, and maybe she would still be sharing her color with the world.

March 25, 2009: It was the 9th anniversary of my sister’s death. I was pulled back again and memories of my sister came rushing in. Among them was another drawing created by my sister the artist. A person’s face was depicted in pencil—gray. There were no rainbows. It reminded me of the character whose face melted off in “Raiders of the Lost Ark” (as a kid, I was too terrified to watch this scene). The sketch was tortured, gruesome. The artist’s signature at the bottom was familiar: “Brittany Baganz. Age 10… Today’s date is March twenty fifth, nineteen ninety two.” Again, time stopped. Exactly eight years after the melting face was sketched, the illness that shrouded my sister in gray and hid her color stole her entirely from the lives of those who love her. Brittany died on March 25, 2000—alone in a seedy hotel room in Orlando, Florida. She attempted to ease the pain of her illness with heroin, and it killed her. The “friends” that enabled her ran away when she showed signs of trouble. My sister died all alone. If only I had been there, she wouldn’t have been all alone, and maybe she would still be sharing her color with the world.

I listened to and watched the video for “Artist in the Ambulance” by Thrice. This reminded me how much I appreciate those whose career is to fight for the life of another. My sister died of an overdose, but dedicated medical personnel fought to revive her. The ambulance company that transported her on March 25th, 2000, contacted my mom a few months after that day and inquired about the bill for that service. Brittany had caused my family enough pain, and the thought that now we again had to pay for her poor choices left me seething with anger. I adamantly advised my mom against paying the balance, but she sent out a check. She said, “Nicole, her friends left her there alone to suffer; these strangers fought for her to live.” I immediately realized that I had much to learn. The lyrics “My world goes black before I feel/ An angel steal me from the greedy jaws of death and chance/ And pull me in with steady hands. Giving me a second chance/ The artist in the ambulance/ I hope that I will never let you down/ I know that this could be more than just flashing lights and sound/ Can we pick you off the ground” echoed in my mind.

March 25, 2010: I had a long day at work in the lab. I finally made my way to my car and thought about my sister. Suddenly, an enormous, beautiful monarch butterfly narrowly missed colliding with my nose. It settled on a branch next to me. I stopped. My trek home was interrupted—and I was thankful. I thought of my favorite magnet on the refrigerator in my kitchen: “Just when the caterpillar thought the world was over, it became a butterfly.” My sister went from butterfly to caterpillar—her illness of despair crushed her brilliant wings and crashed her into the ground. But my sister provided the reverse metamorphosis in my own life, caterpillar to butterfly. Because of Brittany and the numerous others in my life afflicted by mental illnesses, I was motivated to become a scientist to try to uncover the fundamental causes of psychiatric disease and develop ways to alleviate the pain that so many bear. Having recently defended my Ph.D. in San Antonio, I was ready to take a new position as postdoctoral fellow at Vanderbilt, where I could expand on my current knowledge, continue my research, and find new treatments for mental illness. My sister remained a primary motivation for my career choice. As Dr. Elder said, Brittany strayed out of the lines, and he was right—in so many ways. For me, my sister threw me out of my line of balance. I will never be the same. If it had not been for her, my life path might have been drastically different. I trained in classical dance for more than 20 years, and when I started college, I had dreams of dancing professionally. Sometimes I imagine what my life would be like if I had become a dancer instead of a scientist. But then when the experiments work, and we find another potential target for treatments for mental illness, I am reminded why I chose the science road.

I kept the butterfly experience in my heart and traveled home. I listened to and watched the video for “Stand” by Rascal Flatts. The lyrics, “On your knees you look up and decide you’ve had enough/Then you stand” reminded me that every March 25th, I wanted to lie there in the ruin of my own self-pity and defeat. I realized that I could have stayed there in the rubble of my own selfishness and sorrow. But I chose to get up and fight for something bigger than me. As painful as it was, I got back up, and now I keep getting up. My work, doing my research, remembering Brittany and making peace with her life is exhausting, but there is a powerful strength in standing.

March 25, 2011: It was the 11th Anniversary. I reflected on my recent relocation to Nashville. On April 30, 2010, I moved to Nashville to start a new position as postdoctoral fellow at Vanderbilt. Historic flooding occurred the day after I moved in. I didn’t have internet or cable service yet, so I relied on my FM radio to keep me updated on what was going on in my new world. It sounded like the Apocalypse out there, and while I was afraid to venture outside of my 3rd floor apartment, I wanted to reach out and assist my new Bellevue neighbors who were suffering. Again, I found myself in a position of feeling helpless and useless to people who were in need of relief. I watched and was impressed by the city of Nashville as it banded together and recovered swiftly from the terrible disaster. Since that day, I’ve gotten to know Nashville and its residents. From what I witnessed in the wake of the flood, I now think of Nashville as a collective group of artists in ambulances. I saw strangers on street corners offering water and food, neighbors helping to rebuild houses, acquaintances consoling strangers who had lost their loved family members, friends, pets, and material possessions.

In July, as Nashville was recovering from the flood and I was leaving the lab, an Eastern Tiger Swallowtail butterfly narrowly missed colliding with my head. Déjà vu. But again, I was thankful. I paused, to take a snapshot this time. My thoughts returned to the butterfly effect and my sister. This reminded me of a Native American proverb: The soul would have no rainbow if the eyes had no tears. This idea projected me into scientist mode. An electron is a negatively charged particle that has the remarkable ability to “jump” to a higher energy orbital (“plane” or “line”) if it receives (and accepts) light energy. Light energy = color. I realized that Nashville and I had a lot in common. We decided not to drown in our own tears but to allow them to be a prism for the light inside. And then I listened to “Beautiful Day” by U2. The lyrics “After the flood all the colors came out…” lifted my spirit. My love for Brittany has been a light through my tears and has taught me to fly in search of redemption for her and all Dinosaur Rainbow Monarchs. My sister illuminated life for me, and the vision is painted with hues from an expansive palette. And I know that right now, from her perspective, she’d look at me on the ground and say the same.

In July, as Nashville was recovering from the flood and I was leaving the lab, an Eastern Tiger Swallowtail butterfly narrowly missed colliding with my head. Déjà vu. But again, I was thankful. I paused, to take a snapshot this time. My thoughts returned to the butterfly effect and my sister. This reminded me of a Native American proverb: The soul would have no rainbow if the eyes had no tears. This idea projected me into scientist mode. An electron is a negatively charged particle that has the remarkable ability to “jump” to a higher energy orbital (“plane” or “line”) if it receives (and accepts) light energy. Light energy = color. I realized that Nashville and I had a lot in common. We decided not to drown in our own tears but to allow them to be a prism for the light inside. And then I listened to “Beautiful Day” by U2. The lyrics “After the flood all the colors came out…” lifted my spirit. My love for Brittany has been a light through my tears and has taught me to fly in search of redemption for her and all Dinosaur Rainbow Monarchs. My sister illuminated life for me, and the vision is painted with hues from an expansive palette. And I know that right now, from her perspective, she’d look at me on the ground and say the same.

August 17th, 2011

What a beautiful and heartfelt story. It is so sad how Brittany left the world, but the fact that you have made some sense of peace and purpose from it reminds us of the innate goodness in the world. I hope that you make a difference in some other family’s life-and touch another Brittany-so they will never know youru00a0pain. You are the butterfly.