Vanderbilt researchers bring paleoecology into the 21st century

By Andy Flick, Evolutionary Studies scientific coordinator

Science is an inherently collaborative endeavor. When a respected colleague courteously disagrees with your point of view, it can lead to great new papers, perspectives and collaborations.

In that same vein, feedback from editors and reviewers of academic journals is an often-understated driver of new research directions. Assistant Professor of Earth and environmental sciences Simon Darroch, found this to be the case for his new paper examining the differences between geographic ranges of species historic and living.

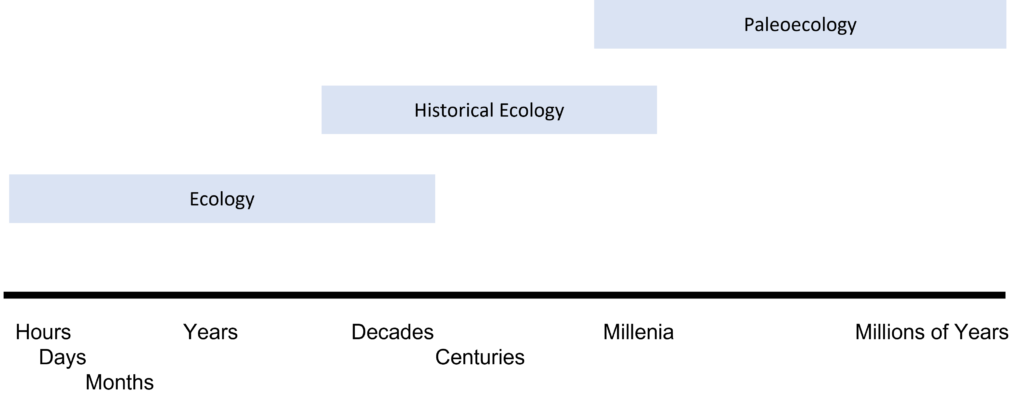

In a precursor to the current paper, “Integrating geographic ranges across temporal scales”, an editor was hesitant that historic ranges and modern ranges could be defined as equivalent, since historic ranges are created using “time-averaged” records.

“This rankled us, so we’re hoping that this new framework will bring paleontologists and ecologists closer together and put us on a common conceptual footing, so that we can work towards answering bigger questions in ecology and evolution,” said Darroch, also Evolutionary Studies seminar series committee member.

The current paper was published in June 2022 in the journal Trends in Ecology and Evolution. Darroch and Associate Professor of EES Malu Jorge published this manuscript with colleagues from Oxford and Towson Universities.

Darroch explained that the concerns did not take into account that current ranges are also time-averaged. It is easy to imagine a species range of buffalo in Yellowstone National Park. The range of those buffalo is the entire park. While an individual buffalo does not cover the entire park, it does not mean that all of Yellowstone National Park is not the range of buffalo. It means that the range is time-averaged over the course of several buffalos’ lives–or even several generations of buffalo.

Understanding how geographic ranges of extinct species can be related to geographic ranges of living species can wield great insights. “We’re hoping to use the fossil record to understand how geographic range size correlates with extinction and speciation and how geographic ranges of species change in the aftermath of mass extinction events,” Darroch said. “This will help us understand the deep-time processes that are responsible for present-day patterns in biogeography.”

“Historical geographic range studies offer a deep time perspective and can tell us [for example] which species are most at risk over extinction events,” Darroch said. “I’m hoping that this framework encourages more collaboration between people who work with modern versus fossil organisms to answer these questions.”

To inspire future collaborations across the field, Darroch worked with Jorge, a conservationist who studies neotropical mammals, a set of animals including llamas, tapirs, deer species, pigs, jaguars, pumas, a variety of opossums, many rodents and fishes and extremely rich insect and bird populations.

“Professor Malu Jorge was crucial to putting these ideas together–she’s a modern ecologist and one who is learning to love the fossil record!”

The feelings were mutual, according to Jorge. “Professor Simon Darroch was an incredible leader and was able to identify how each participant can provide valuable and unique information and insights to the project,” said Jorge. “He made me feel at ease working with paleontologists, even though I am a present-day ecologist. He was great at seeing the big picture and bringing complementary and unique knowledge together to advance the fields of paleo and modern ecology, to bring them closer together.”

This research was made possible by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, which is sponsored by the Federal Ministry for Education and Research in Germany. The work was also supported by the Leverhulme Trust Prize and grant #DGR01020 and Natural Environment Research Council (NE/V011405/1).