Vanderbilt Biologist investigates specialization and its impact on cultural evolution

By Kelly Tingle, Evolutionary Studies communications assistant

The cultural evolution of a population depends not only on size but also on the degree of specialization within a population, according to a new study published last month by a team of scientists including Biological Sciences Assistant Professor Nicole Creanza.

The study found that populations can increase their cultural repertoire by subdividing knowledge into smaller groups, but the total group must be sufficiently large for specialization to be advantageous. Specialization in smaller communities may create vulnerability to loss of cultural knowledge if dynamic events like environmental change or illness occur.

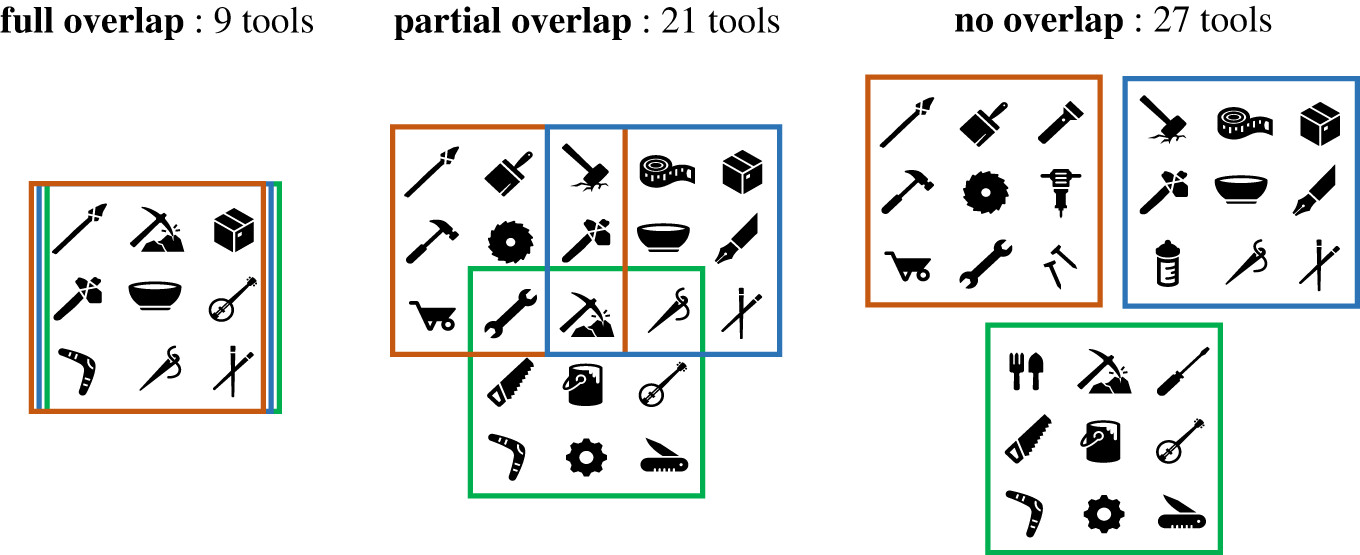

Caption: Vanderbilt Biology Professor Nicole Creanza found that subdividing skills and knowledge within a community can increase total cultural knowledge, but depending on community size, may also increase vulnerability to cultural loss. Image from Ben-Oren, Kolodny, and Creanza (2023).

The authors reached these conclusions by developing a model in which tools, which symbolized cultural traits, were divided amongst populations with varying degrees of specialization. As time increases, new tools are invented, and the rate of invention is linearly related to population size. New tools can be lost before assimilation and established tools can be lost by chance. In addition, the more tools sustained collectively within a group the higher the degree of tool loss, due to knowledge capacity limits.

“The idea is that it might be a double-edged sword to specialize, particularly if the population is too small,” explained Dr. Creanza of the main findings from the study. “We have tried through this model and a couple others to think about why you can’t always predict the repertoire size of a population. One idea is specialization.”

“If there is a divide and conquer strategy where small groups of people do apprenticeships and you have a situation where there is specialization, you can get a larger overall cultural repertoire in the population, but a lot of the knowledge is sequestered in small groups of people. It might be less resilient to disruption or susceptible to loss,” said Creanza.

Creanza described that while community size is relevant, it is important to consider other more nuanced factors in cultural evolution and the development of tool complexity, such as tool structure, cultural repertoire, and interconnectedness with other populations.

This study builds on previous studies from Creanza and co-author Dr. Oren Kolodny of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, who met while the pair were postdoctoral researchers at Stanford University, on cultural evolution and the appearance of multiple punctuated bursts of human innovation in the archaeological record. Creanza explained that previous cultural evolution models are traditionally based on population genetic models, but unlike genetic mutations, novel ideas may happen not just by chance but also by building upon and combining with other existing innovations.

“Our initial finding was all you needed to explain punctuated bursts of cultural evolution. You didn’t need to invoke environmental changes or large-scale disruptions to the human population to be able to explain why there might be a burst of innovations in the cultural record,” explained Creanza of the team’s findings from 2015. “Not that at any given point in the archaeological record there couldn’t have been some environmental change that caused humans to invent a lot more stuff or change their cultural repertoire, but there didn’t have to be. The cultural burst wasn’t necessarily evidence for a big shift.”

Creanza and her lab at Vanderbilt have applied similar models of human cultural evolution to better understand cultural evolution in bird populations. Creanza described that the extent to which a population of birds can sustain a complex repertoire may interact with the size of the population. “You can envision that if you replace tools with syllables, the most complex and hard to learn syllables might be the first that would get lost if the population size were reduced or if the population went through a big change or if there were a harsh environment.”

Funding: Funding for this study was provided by the US–Israel Binational Science Foundation (BSF) and the Israel Science Foundation (ISF; grant no. 1826/20), the National Science Foundation (NSF BCS-1918824) and the John Templeton Foundation (grant no. 62187).

Citation: Ben-Oren, Y., Kolodny, O., and Creanza, N. (2023) Cultural specialization as a double-edged sword: division into specialized guilds might promote cultural complexity at the cost of higher susceptibility to cultural loss. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 378: 20210418. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2021.0418