The Legacy of Chancellor Kirkland: Education, Evolution, and the Scopes Trial

By: Neomi Chen, Evolutionary Studies communications assistant

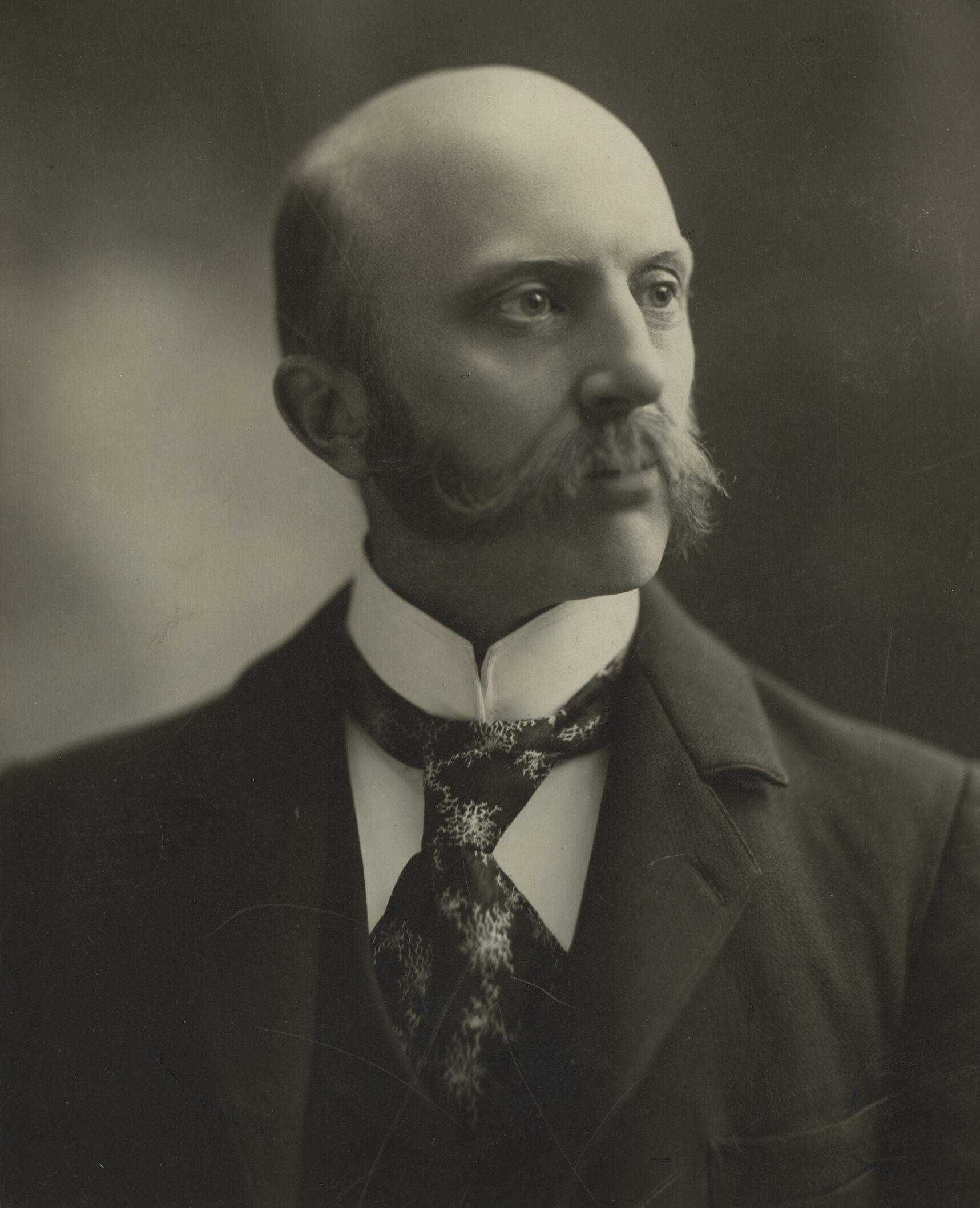

Chancellor James Hampton Kirkland was a significant figure in the education landscape of the early 20th century, particularly recognized for his leadership of Vanderbilt University after the 1925 Scopes Trial. His views on evolution and education were instrumental in shaping the discourse around these topics at Vanderbilt University and beyond. His steadfast support for academic freedom and the teaching of evolution, even in the face of widespread criticism, marked him as a forward-thinking leader committed to intellectual growth.

The Scopes Trial in Dayton, Tennessee (July 10-July 21, 1925)

On March 21, 1925, the Butler Act was signed into law and prohibited public school teachers from teaching human evolution or that “man descended from a lower order of animal” in Tennessee state. Those in support of the law believed that man did not come from a monkey and that nothing shall be taught in public schools that shall “take our Bible away from us.” Therefore, when high school teacher John T. Scopes was charged with violating Tennessee’s Butler Act by teaching evolution in a public school, his trial attracted national attention. The Scopes Trial, formally known as The State of Tennessee v. John Thomas Scopes and commonly referred to as the “Scopes Monkey Trial,” pitted modernists who believed that evolution could coexist with religious faith against fundamentalists who argued that the Bible’s teachings should take precedence over scientific theories.

The trial became a public spectacle, with prominent figures like William Jennings Bryan arguing for the prosecution––famously claiming that “The Bible is good enough to live by and to die by” ––and Chicago criminal lawyer Clarence Darrow defending Scopes. When the jury was picked, nine out of thirteen jurors were farmers, and only one juror was a non-church member. According to a July 10, 1925, Chattanooga Daily Times newspaper, evolution was a new idea to the average Tennessee citizen. Scopes was eventually found guilty and fined $100 (equivalent to $1,700 in 2023). The supreme court of Tennessee later ruled the case a mistrial and it was never retried. The trial highlighted the deep cultural divide in America over the issue of evolution and education. The case also raised questions about academic freedom, the role of science in education, and the intersection of religion and government.

Chancellor Kirkland’s Stance on Education & Evolution at Vanderbilt

Vanderbilt University is squarely positioned in the center of Tennessee, just one-mile due west from where the Butler Act became law. Chancellor Kirkland, who led Vanderbilt University during this tumultuous period, firmly believed in the importance of academic freedom and the advancement of scientific knowledge. In June 1914, Kirkland oversaw the separation of the university from the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. According to a October 16, 1925 Chattanooga Daily Times newspaper, he saw the teaching of evolution as essential to a well-rounded education, and he resisted the pressures from both religious and political groups that sought to curtail the teaching of evolution at Vanderbilt.

On October 15, 1925, Vanderbilt celebrated for 3 days its semicentennial anniversary, amid much local and national acclaim. At the start of these festivities, people highly anticipated Chancellor Kirkland’s announcement regarding the outcome of the Scopes Trial to which he proudly claimed, “The answer to the episode at Dayton is the building of new laboratories on the Vanderbilt campus for the teaching of science.” This was his attempt to offer students a cure for fundamentalism. He went on to argued that Vanderbilt needed to stimulate a broad culture, a scientific habit of thought and scholarly attainments

Kirkland’s support for evolution didn’t end there; in November 1925, he announced his plan to raise $4,000,000 for the advancement of science and arts at Vanderbilt and in Tennessee. Since VU––as a private institution––doesn’t receive funds from state or church organizations sympathetic to the Butler Bill, Kirkland ensured freedom of teaching existed at Vanderbilt. According to The New York Times, before this statement, Vanderbilt had completed a medical facility costing $3 million and procured for the medical college a special endowment of $5 million through gifts from the General Education Board and the Carnegie Corporation.

In February 1926, Kirkland made another broader call to action at a conference held at Vanderbilt. Kirkland felt that the South was lagging in education compared to other regions in America

He insisted, “we must find some way of making it spiritual and intellectual. The correction of these things lies in your hands as representatives of the press of America, as well as in ours representing educational institutions.”

Support

After Kirkland’s call for evolution education, Edwin Mims, a professor of English at Vanderbilt, praised Kirkland for his clear and eloquent articulation of the university’s mission in his paper published in the South Atlantic Quarterly in August 1924. Mims admired Kirkland’s commitment to promoting intellectual rigor and his resistance to the narrow-mindedness that sought to limit the scope of education. In August 1926, Chancellor Kirkland published a chapter titled “Evolution and Its Limits” in the Methodist Quarterly Review and the South Atlantic Quarterly. He demonstrated his liberal thinking and understanding of evolution by carefully distinguishing between Darwinism and the modern theory of evolution and pointing out evolutionary problems that have not yet been solved.

Other voices chimed in support of Kirkland’s actions. In an address at the semicentennial celebration of Vanderbilt, President R. E. Blackwell of Randolph-Macon College claimed that “the South has made a more gallant fight than the fight for democratic ideals in education.”

The Chattanooga Daily Times attributed Kirkland’s nearly-unifying statement as the “most intelligent, the most harmonizing and the most constructive statement yet made touching the issue of evolution that has divided the people of the state and that is dividing the Christian churches.”

Criticism

However, Kirkland’s stance also drew significant criticism.

In a June 26, 1925, Morristown Gazette Mail newspaper publication, Judge Henry Neil of Chicago said, “we don’t need the magnificent oratory of William Jennings Bryan to prove the truth of Genesis and the Virgin birth of Christ. Let this nation rebuke the uncalled-for demonstration that in reality places a hypothesis on the origin of Christ!”

From those that generally agreed evolution should be taught in schools, there were also critics. For example, the London press and other international observers expressed skepticism about the state of education in Tennessee, particularly in light of the Scopes Trial. William Jennings Bryan, a staunch opponent of evolution, represented the broader public sentiment that opposed the teaching of evolution in schools.

Dr. John R. Neal, the senior defense counsel in the Scopes case and an alumnus of Vanderbilt, criticized Kirkland for what he perceived as a lack of sufficient support for the defense’s cause. At the semicentennial festivities, Neal reported that he was not satisfied with Kirkland’s statements. He said, “While I found a universal condemnation of the act in their private conversation, there was the most manifest timidity displayed in their public addresses, and it was only by interference that they expressed their public disapproval.” Neal argued that Vanderbilt had abandoned those fighting for religious and educational freedom, particularly pointing out that Kirkland’s public statements were too timid and lacked the force needed to rally support against the anti-evolution law.

Despite the criticism from various spheres of academia and law, Kirkland remained resolute in his support for the teaching of evolution. He understood that the advancement of science and education required the university to embrace modern theories and methodologies, even when they were controversial. His decision to build new laboratories at Vanderbilt for the study of science was a direct response to the challenges posed by the Scopes Trial and a clear statement of the university’s commitment to scientific inquiry.

Chancellor Kirkland’s Legacy

The headline “Daring to Teach Science in Tennessee,” once emblazoned on the Nashville Banner to shame the teaching of evolution, stands in stark contrast to Vanderbilt University’s current motto of empowerment, crescere aude or “Dare to Grow.” This transformation was made possible by Chancellor James H. Kirkland’s steadfast advocacy for advancing education during the Scopes Trial era. His unwavering support for the teaching of evolution at Vanderbilt University were pivotal in shaping the university’s identity as a center for intellectual and scientific progress. Kirkland’s contributions to education extended beyond Vanderbilt. He played a major role in the organization of the Association of American Colleges and the Southern University Conference, helping to elevate the standards of higher education in the South. His influence was recognized by his contemporaries and continues to be acknowledged today as a cornerstone of Vanderbilt’s history and its ongoing commitment to academic excellence.