Rediscovering the Lost Plesiosaur (Cast): Restoring Vanderbilt’s Natural History Museum

By: Andy Flick, Evolutionary Studies scientific coordinator

Embarking on a new research project often brings unexpected discoveries—some intriguing, some novel, but rarely a find of a lifetime. Such a remarkable discovery occurred when university archivist and associate director Kathy Smith stumbled upon a pile of plaster, hidden away for 60 years in a dim, cluttered closet of the Branscomb Quad basement. This plaster turned out to be the long-lost Crampton’s Plesiosaur Cast from the 1870s, missing for nearly six decades.

The Museum’s Glory Years

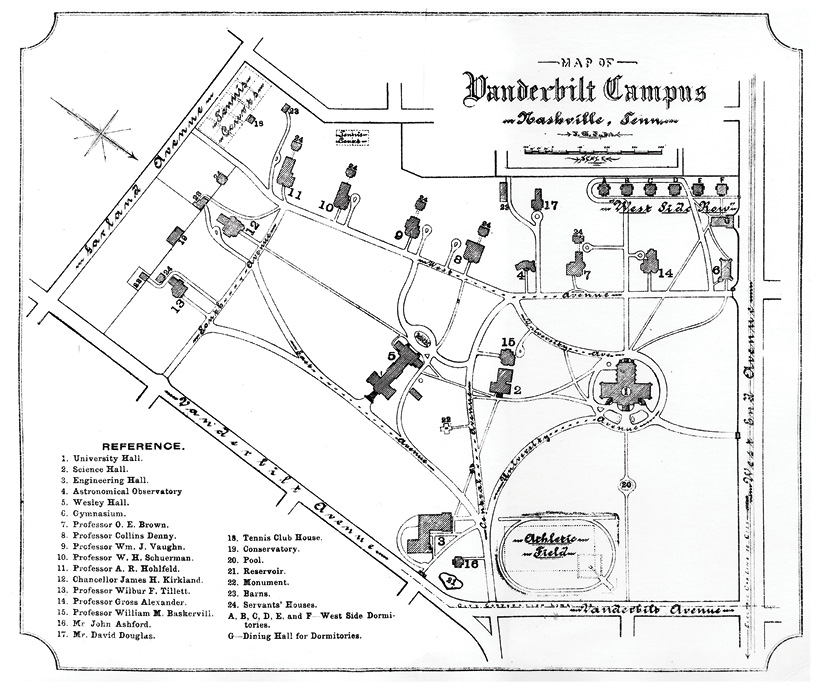

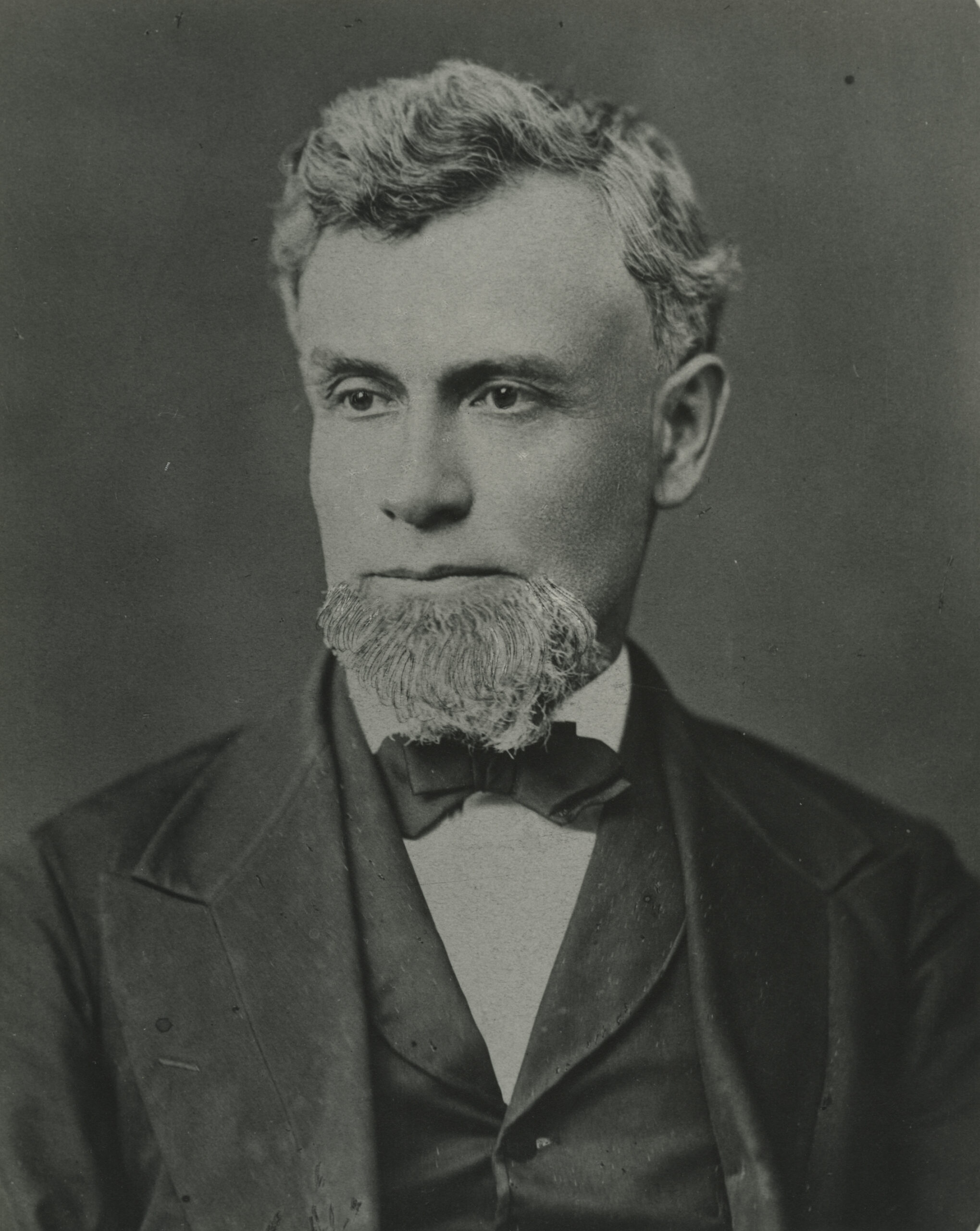

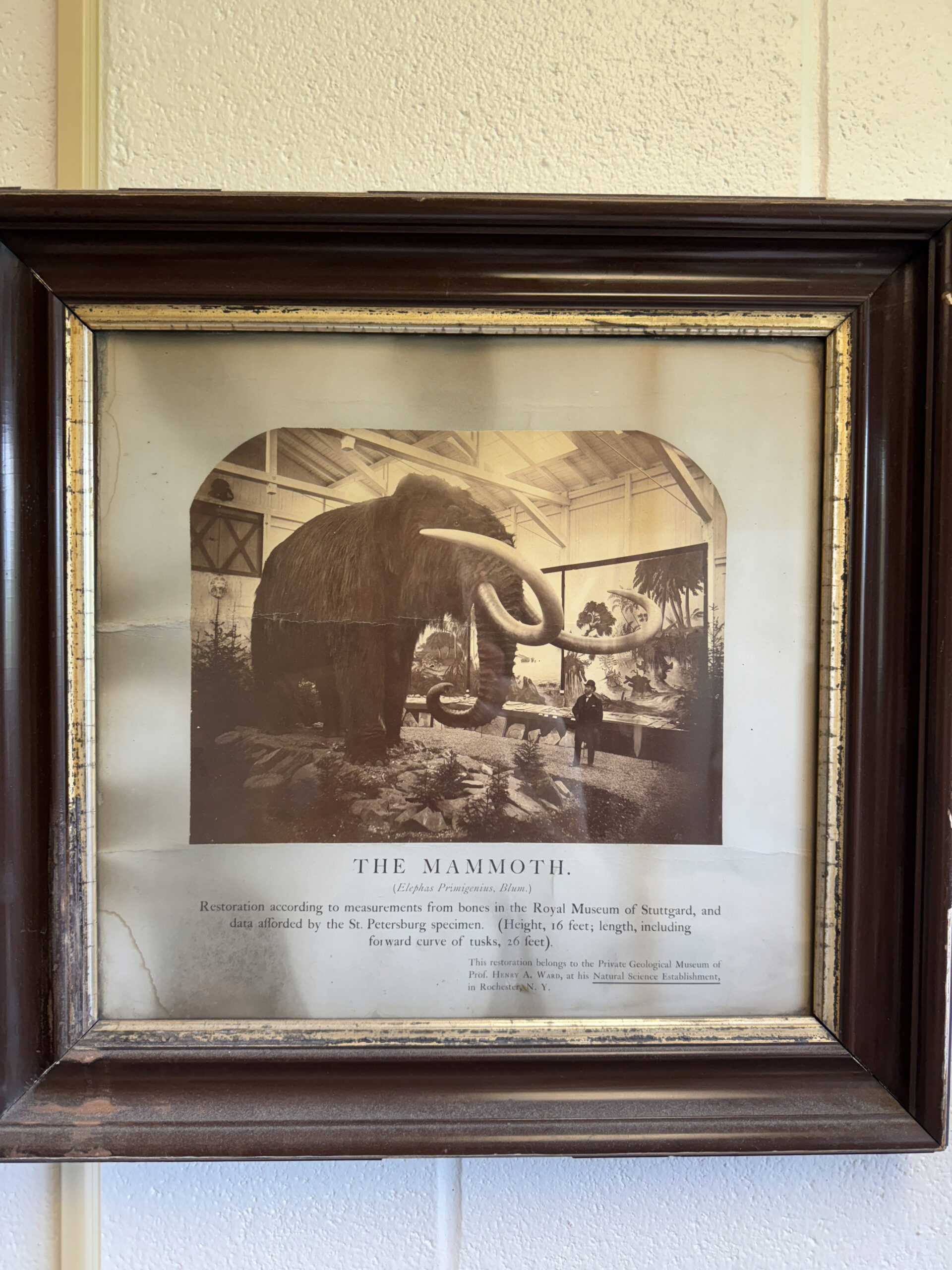

To get the full story, it’s necessary to go back to the beginning. The university was founded in 1873 and the tools necessary for teaching and learning needed to be acquired. James Safford, a local Tennessee educator, was selected as co-chair of the School of Natural History and Geology and was tasked with tracking down geological and natural history resources to outfit a museum. Bringing his own fossil and geology collection, the state of Tennessee was well represented; however, he dreamt bigger and truly lived up to Vanderbilt’s motto of daring to grow. With about $2,000 (~$57,000 today) from Bishop McTyiere at his disposal, he went after the biggest and best fossil casts available – those of the renowned geologist, Henry A. Ward.

Thanks to sleuthing by emeritus Geology professor, Leonard Alberstadt and the Special Collections of the Jean and Alexander Heard Libraries, we know that in May 1875, Safford was on the hunt for minerals and fossils. In June, a plan was hatched with co-chair Alexander Winchell to purchase many of the needed materials from Ward’s Catalogue. While Safford did not have access to the catalogue, a downloadable version is available to see here. By December 1875, Professor Ward’s team had installed the marvelous fossils and casts. This appears to have been just in time as well, for in September of 1876, Professor T. H. Huxley dropped by for a visit to the museum, then on the 3rd floor of Science Hall. Huxley was one of the staunchest advocates of Darwin’s new theory of evolution by natural selection, even known at the time as “Darwin’s Bulldog.” He noted that the marvelously beautiful specimens rival that of much older institutions across Europe.

Here is, indeed a magnificent collection – some of them pronounced by Prof. Huxley to be marvelously beautiful specimens. In this department, himself and Prof. Safford seemed to enjoy a protracted colloquy in a language comparatively unknown to the rest of the company. Of this collection, Prof. Huxley says that while it is not fair to institute comparisons between so young a University and the older institutions of Europe, yet the museum and general appointments of Vanderbilt are remarkably fine and the arrangement excellent. – The Daily American, Nashville, Sept. 4, 1876

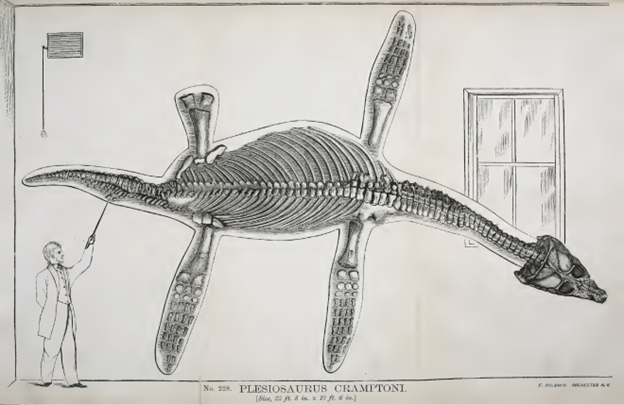

In those early years, every university course register shared the story of the venerable museum. Within the museum descriptions lay the following sentences, “these collections are supplemented by Professor Ward’s celebrated series of Casts. Among these are casts of mammalian and reptilian skeletons, skulls, and bones, the originals of which are rare, or unique, and only to be seen in the British and other foreign museums.”

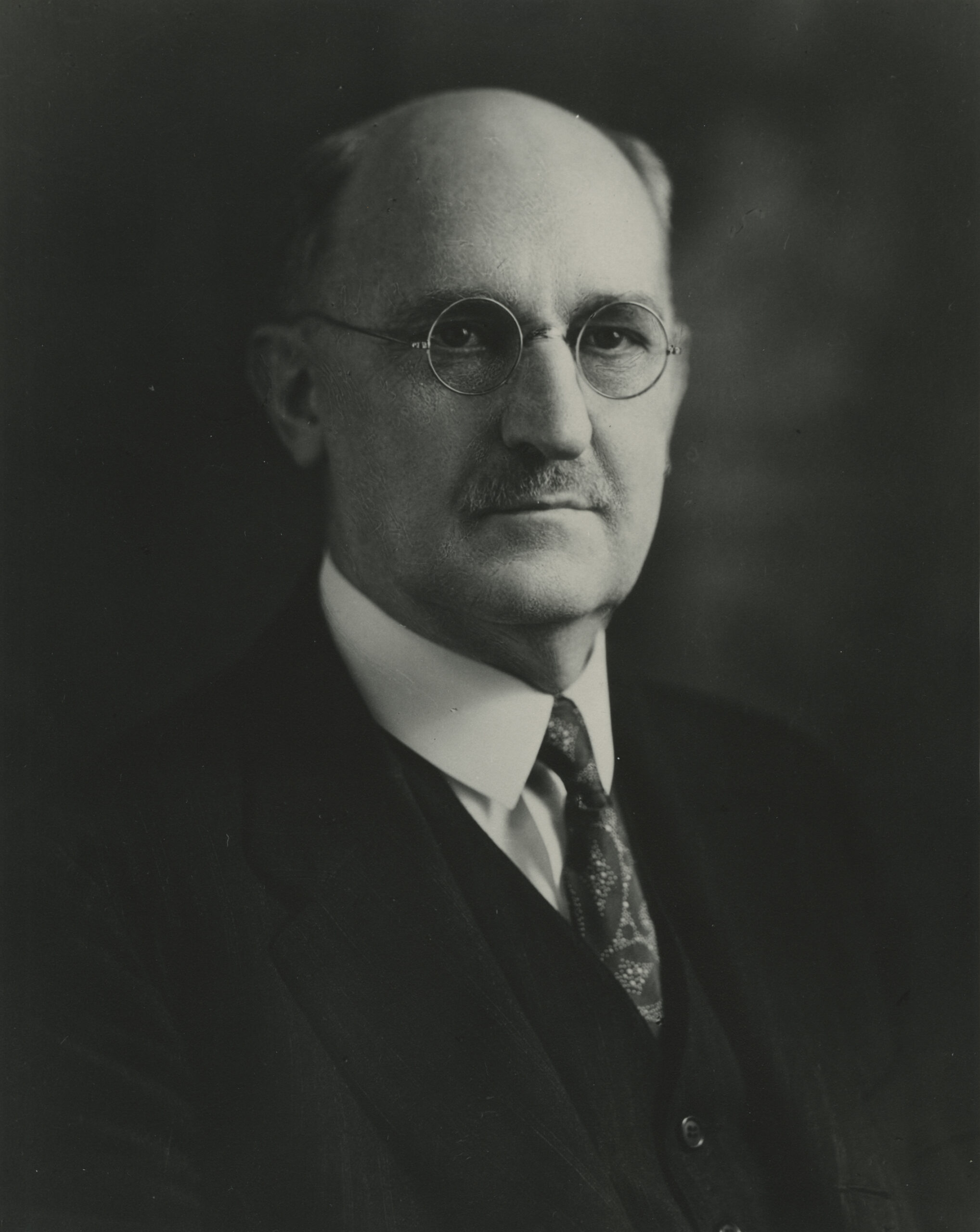

Records of those early years are sparse; Winchell was dismissed in 1878 and Safford destroyed most of his records, but we know the museum was an important part of the university. In 1900, Safford retired and was replaced by L.C. Glenn.

Starting in 1902, Glenn began expanding the museum’s collection of fossils – a few mastodon teeth, bones, and tusks from North Nashville and Mt. Pleasant, shells and sponges from Florida, and a $500 gift from an estate. Glenn put the new fossils to work immediately giving a talk in 1903 titled, “Mastodons in North America.”

Beginning as early as 1907, students looking to pursue a degree in science at Vanderbilt had to write a short essay on the evidence of relationships suggesting evolution. The essay requirement ended, “a few facts indicating the struggle for existence, adaptation to environment, variations of individuals and man’s selective influence [sic] should be pointed out.” Surely, the fossils and casts in the museum would have been of the utmost excitement for a student that could succinctly describe the forces behind evolution.

The Museum’s Downfall

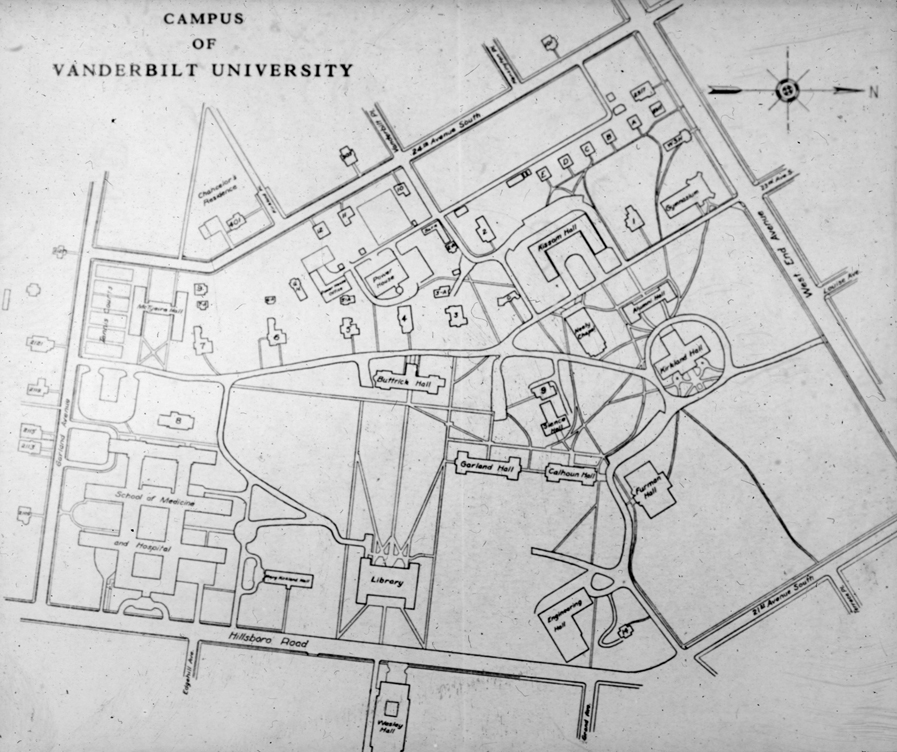

At about the same time – 1907 – 1908, the museum was moved from Science Hall to College Hall. After the move, the museum was housed in two large rooms on the first floor, though the largest of the casts had to be sawed in half to make the move. During these years, researchers from around the country were coming to Vanderbilt to use and study the fossils available. By 1926, however, the glory years were over, and the museum was moved to the basement of College Hall.

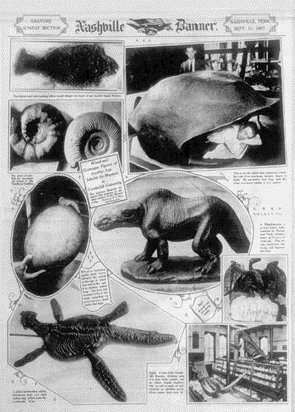

In 1927, just two short years after the infamous Scopes “Monkey” Trial and the university’s semi-centennial, graduate student of geology J. Willis Stovall made a plea in the Nashville Banner to create a proper museum. While laying out the organization of the museum, he noted that the bones (metaphorically and literally) for such a museum already existed at Vanderbilt.

With a final plea, he wrote, “[h]ere is an opportunity for the citizens of Nashville to establish in their midst an institution of inestimable value for the inspiration and education of the youth… Some day, perhaps when it is too late, we will awaken to a neglected duty, with a feeling of guilt that we have allowed invaluable evidence of the earth’s history to be taken from our midst.”

Stovall would one day get his museum at the University of Oklahoma, though Vanderbilt would not.

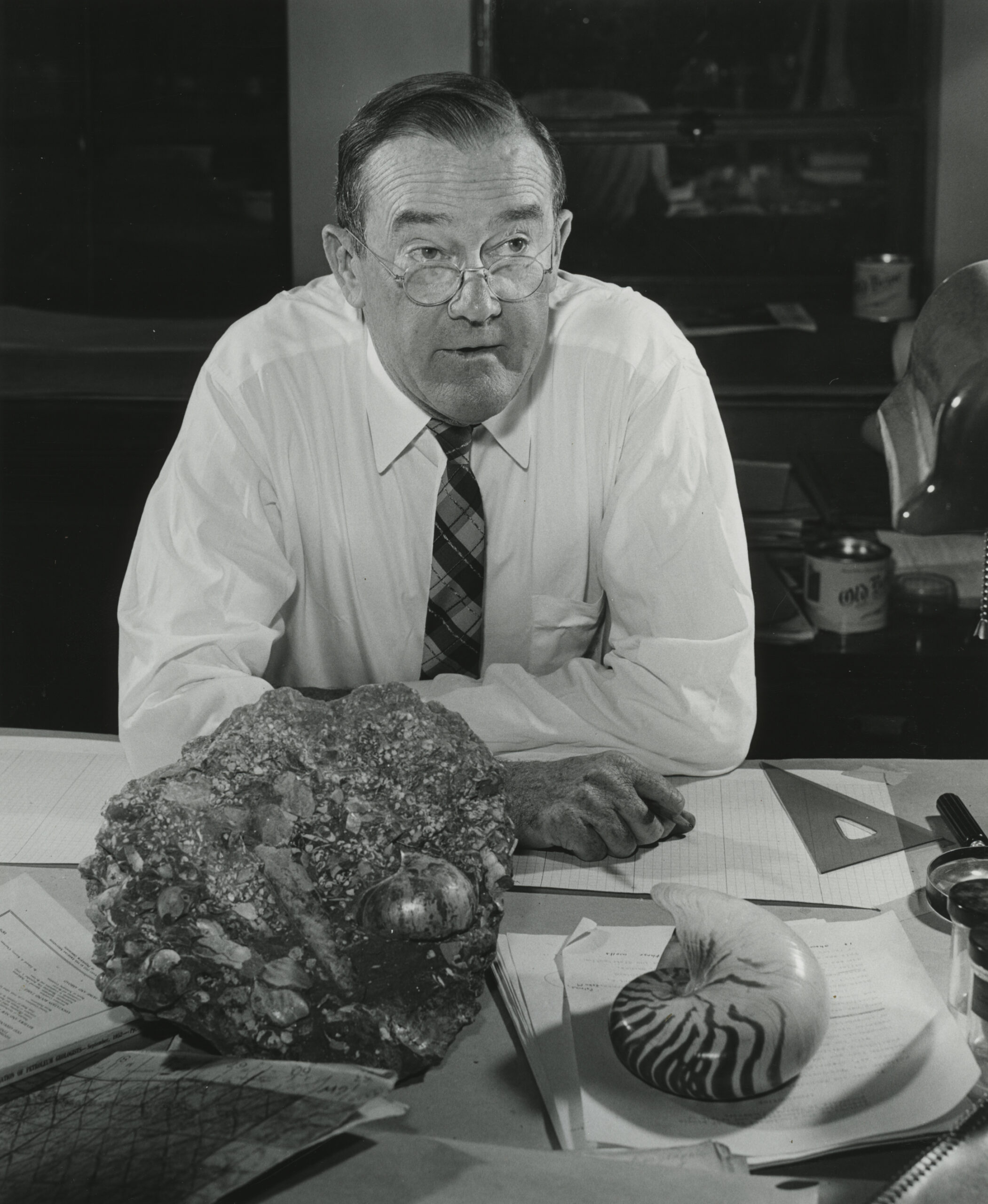

From the 1940s to the 1960s, as the museum languished in the basement, VU alumni and professor Charles Wilson, Jr. taught organic evolution and several courses on paleontology. No doubt inspired by his time at Vanderbilt as a student, Wilson leaned heavily on the natural history collections to supplement his textbook readings and lectures. In a 1965 course book on Vertebrate Paleontology, there is a note in the margins next to the description of the ancient marine reptiles. Written next to “Plesiosaur” was simply “Kirkland Hall.” This is the last evidence of the plesiosaur existing, in a note in the margins of course materials implying the plesiosaur was housed in Kirkland Hall. In 1975, what remained of the collections was moved to the basement of Stevenson Center’s math building. If you find your way down there, you can still see precious few pieces displayed.

There have always been whispers, though, of what might have happened to the once great museum collections.

The Sesquicentennial Grant and Library Team

Enter the Evolutionary Studies Initiative. Founded in 2019 by professor of Biological Sciences Antonis Rokas, ESI aims to unite the dozens of Vanderbilt’s scholars across disciplines that work in evolutionary science or its applications. This includes not just faculty in biological sciences but also folks in medicine working on antibacterial resistance, those in the law school apply natural selection to our understanding of the law and many others. In the five short years (COVID and all) since its inception, ESI has built a strong outreach program, a well-attended journal club course, and several named lecture series featuring luminaries in evolutionary science like Peter and Rosemary Grant, known for their groundbreaking work with Galapagos finches, Neil Shubin the finder of the first tetrapod to walk on land, and Scott Edwards curator of ornithology at the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology. In this new era of evolutionary studies collaboration, ESI applied for and received a sesquicentennial grant from the Chancellor’s office to investigate the history of evolution at Vanderbilt University.

Working along with the university librarians, primarily Smith, this project has already turned up interesting and important stories. Ashley Rogers (BA ’24) investigated and told the story of Alexander Winchell, a once great paleontologist and geologist – even known as the father of geology – with extremely racist views. He was dismissed from Vanderbilt three short years into his tenure. Rogers’s talk on Winchell and academic racism even received the Diversity in Evolution Award by the Society for the Study of Evolution. Of the same era, a short, cartoon story was created for Paul M. Jones, an alumnus of the natural history and geology department at Vanderbilt that single-handedly started the program in biology before his untimely death in 1899. A story on Rogers and the cartoon of Jones can both be found in the Spring 2024 version of Evolutionary Studies – the Magazine. Moving forward, one major aim of this project is to build a virtual museum rivaling that of the original natural history museum.

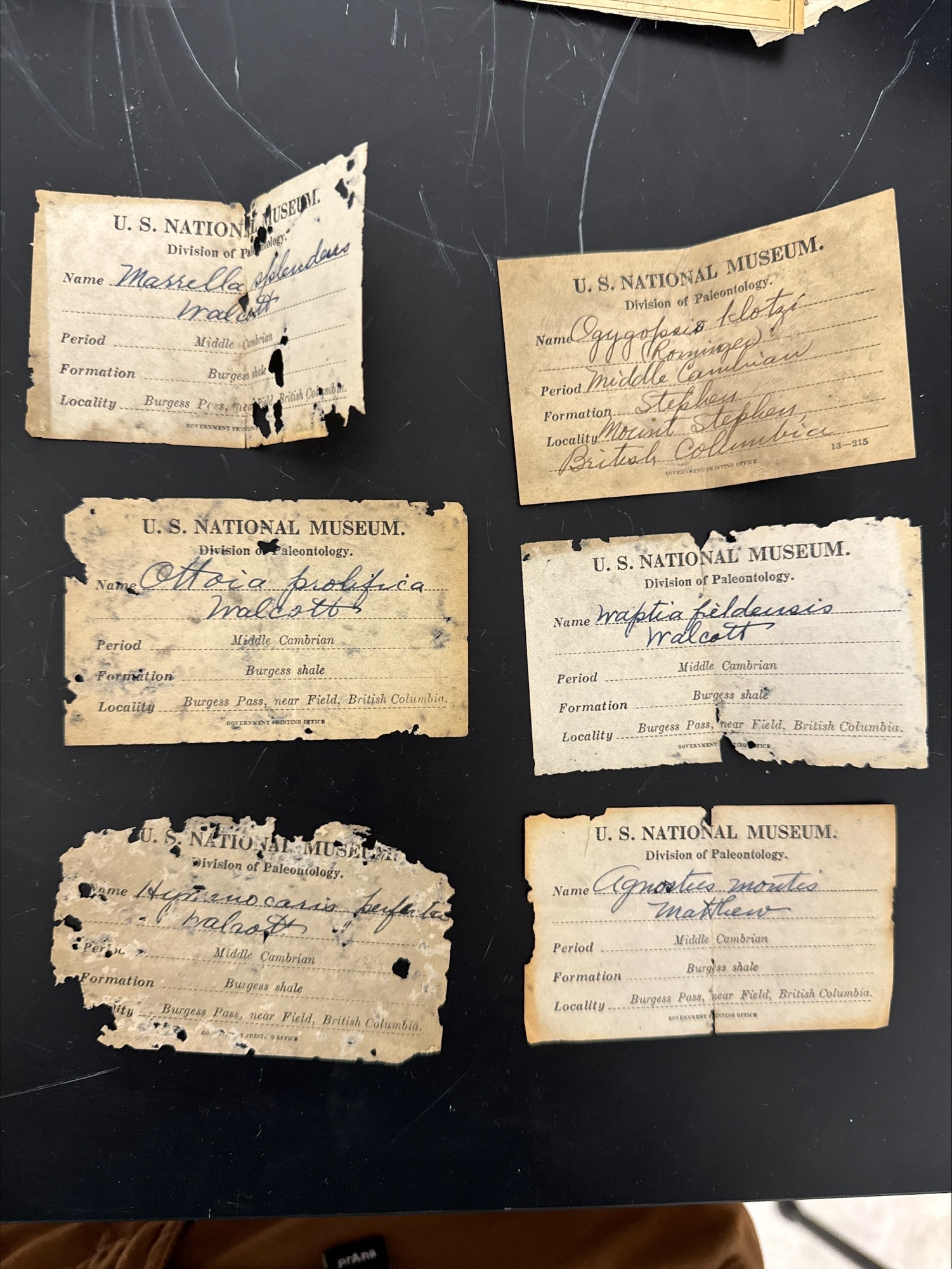

Neil Kelley, ESI member, assistant professor of Earth and environmental sciences, and Vanderbilt’s resident plesiosaur-ologist has been hard at work identifying what remains of the old museum. Aided by a team of graduate, undergraduate, and even high school students, Kelley spends long days sifting through loose fossils, misidentified fossils, and lost scraps of paper with chicken-scratch scribbles. As part of the sesquicentennial team, Kelley often helps identify old pieces of the museum. In fact, the first piece of the old museum properly identified from the colorized photo above is a small, framed picture on the back wall. As serendipity would have it (often a driver of discovery), that very image of a mammoth was hanging right on the wall in Kelley’s office. If you zoom and enhance like in a good crime drama, you can see the same stain patterns in the photo today as were on the one in the original museum.

The EES department is working on a sesquicentennial grant of their own. Their project is to create a rock garden useful for teaching with examples of the wonderful geology of Tennessee and some of the fossils of the area. In fact, the petrified wood found by none other than Wilson will be one of the centerpieces. These steps – the basement in the math building, the mammoth in Kelley’s office, the petrified wood of the rock garden, the virtual museum – are small but important for improving the natural history education, and indeed fascination, that once featured so heavily at Vanderbilt.

The Plesiosaur

One fateful spring 2024 day, Smith was called to duty to investigate a bronze bust in the basement of the Branscomb Quadrangle. Her co-worker, Scott Martin, let her know there was something lurking in a dark corner – tucked behind an old, empty filing cabinet.

“I looked around the corner to this little crypt-like area. Scott said, ‘Kathy, you’re going to want to see this!’ Behind a bunch of old filing cabinets that had been knocked down, in the back corner hidden away there was something big. I knew this was something cool, so I took out my phone and grabbed a picture to send to Andy the evolutionist,” Smith recalled.

If it hadn’t been for working with ESI, Smith said she may not have recognized it as anything more than just some old plaster. The photos were dark with bad lighting, but ESI urged Smith to keep the plaster safe. Smith agreed to have the plaster pieces moved to the storage space of Special Collections. Upon closer investigation, ESI was able to identify the cast as the missing plesiosaur of days long gone.

Smith continued, “Andy came into my office and said, ‘Kathy – do you know what you found? It’s the lost plesiosaur – missing since the 1960s!'”

The plaster is quite old and fragile, the head is missing, but this is one of only six such skeleton casts in the entire world. The original fossil, in the National Museum of Ireland, was taken apart via sledgehammer to be moved and took years to rebuild just the skull. One of the six casts has completely re-cast flippers. Another has the wrong flippers. Even without a head, this is truly the find of a lifetime and just the centerpiece needed to rebuild the once great natural history museum at Vanderbilt. When rebuilt, the cast will stretch nearly 24 feet long and be the type of world-renowned display fitting of Vanderbilt’s motto – Dare to Grow.

It’s left to wonder what other of these historic pieces remain in the dusky basements across campus. In this regard, ESI’s efforts are aimed at locating and restoring the lost gems of the university. We’ve found the plesiosaur, but what of the giant sloth? ESI is developing spaces around campus that expose students to the wonders of natural history. For example, visitors can come to the 7th floor of MRBIII and see our hallway with a coelacanth and a hominid known as “Lucy,” head down to the Stevenson Center 7’s second floor to see our display cabinet of primate skull casts or wander the university grounds and admire the living arboretum that is campus. Why should students in the 1800s be the only ones to experience the wonder of looking upon a 24-foot-long sea monster and being immersed in the time of dinosaurs?