History of Evolution at Vanderbilt

This page is the home of the History of Evolution at Vanderbilt Project. Below, find a list of faculty and alumni that have played an important role in evolution education and research at Vanderbilt. Undergraduate students currently working on this project are Neomi Chen and Nick McCoy.

Undergraduates that worked on this project in the past are Sheila Chau, Dante Hernandez, Olivia Quiroga, Ashley Rogers, Kaitlyn Russell, Tara Stanley, Carly Stewart, and Chuyuan (Bill) Xu. In general, images are from the Vanderbilt University Media Database or in the public domain.

By: Nick McCoy, Evolutionary Studies undergraduate communications assistant

James Merrill Safford, born in Putnam, Ohio in 1822, was a pioneering geologist whose extensive contributions led to great strides in related fields over his 52-year career. Safford’s contributions to understanding Tennessee's geological and natural resources played a pivotal role in establishing Vanderbilt as the premier academic institution in the state.

Safford's career began to take off during his time at Yale, where he conducted chemistry research through the “Silliman” lab in 1847. Benjamin Silliman founded the American Journal of Science and Arts in 1818. The journal's success revolutionized scientists' interactions and idea-sharing, with Silliman and the journal fostering cohesion and purpose among urban scientists, according to Baatz. This mindset became instilled in Safford’s approach to his work. By the end of his time at Yale, he earned a Ph. D. — one of the earliest doctorates in geology. Safford left for the American South and began teaching at Cumberland University. From 1848-1873, Safford taught chemistry, mineralogy, and geology before moving to the growing city to teach chemistry at the joint University of Nashville Medical School and Vanderbilt University. During this time, Safford’s work in medicine and geology earned him an M.D. from the University of Nashville.

Safford's career began to take off during his time at Yale, where he conducted chemistry research through the “Silliman” lab in 1847. Benjamin Silliman founded the American Journal of Science and Arts in 1818. The journal's success revolutionized scientists' interactions and idea-sharing, with Silliman and the journal fostering cohesion and purpose among urban scientists, according to Baatz. This mindset became instilled in Safford’s approach to his work. By the end of his time at Yale, he earned a Ph. D. — one of the earliest doctorates in geology. Safford left for the American South and began teaching at Cumberland University. From 1848-1873, Safford taught chemistry, mineralogy, and geology before moving to the growing city to teach chemistry at the joint University of Nashville Medical School and Vanderbilt University. During this time, Safford’s work in medicine and geology earned him an M.D. from the University of Nashville.

As Vanderbilt opened in the fall of 1875, Safford was handpicked to co-chair the Natural History and Geology Department with Alexander Winchell. At the time, Safford’s respected reputation in Tennessee and impressive distinction as the only Vanderbilt professor to have obtained an M.D. and Ph.D bridged a gap between different spheres of scientific influence and inquiry between both men. Safford taught courses on lithological and economic geology, botany, and mineralogy. Winchell and Safford split paleontology into zoology and botany, with Safford teaching the latter. According to university records, from 1876 to 1878, Safford expanded his teaching responsibilities to include zoology, paleontology, lithology, historical and dynamical geology. Safford's tenure at Vanderbilt covered a broad spectrum, including post-graduate classes in specialized topics like blow-pipe analysis and field geological studies. During this period, Safford took on additional roles as Secretary of the Faculty and Professor of Chemistry.

As the pair continued to co-chair the department, one of Winchell's publications, Adamites and Pre-Adamites, sparked backlash from both Vanderbilt and Southern Methodists due to the scientific assertions made that Black people were the original humans and the White majority evolved after. By 1879, Winchell had been released from the university. Safford was left in charge, and he became the living embodiment of Vanderbilt's School of Natural History and Geology. Safford continued to teach his core subjects of natural history, geology, and botany while adding courses on zoology, including general principles, classification of animals, and paleontological studies. Such classes utilized Nicholson's Textbook of Zoology and incorporated scientific views on evolution from the Manuals of Zoology and Paleontology. The latter discusses a theory of evolution rooted in the evolution of organic types, species emergence, morphological persistence, extinction, and the absence of transitional forms, all supported by paleontological evidence. Safford eventually became the Dean of the Pharmaceutical Department from 1885 to 1900, drawing on his experience teaching pharmaceutical courses and insight into natural resource production.

Elsewhere on campus, Safford worked on sourcing and cataloging artifacts for the University’s Museum, located in Science Hall. The Museum became the home of the Natural History collection and Cabinets of Geology. The Museum’s purpose was to use its archives for instructional purposes and prestige. According to course catalogs, the collection included fossil remains, a variety of Paleozoic forms, and mammalian and reptilian skeletons of impressive numbers. In addition, there was a large amount of minerals and rocks — an almost full collection of Dana’s System of Mineralogy, which included close to the total 352 mineral species categorized by chemical compounds. These artifacts were sources from Tennessee, nearby states, and even Europe. Safford's collection also found its way into the museum in the form of nickel and iron ore.

Elsewhere on campus, Safford worked on sourcing and cataloging artifacts for the University’s Museum, located in Science Hall. The Museum became the home of the Natural History collection and Cabinets of Geology. The Museum’s purpose was to use its archives for instructional purposes and prestige. According to course catalogs, the collection included fossil remains, a variety of Paleozoic forms, and mammalian and reptilian skeletons of impressive numbers. In addition, there was a large amount of minerals and rocks — an almost full collection of Dana’s System of Mineralogy, which included close to the total 352 mineral species categorized by chemical compounds. These artifacts were sources from Tennessee, nearby states, and even Europe. Safford's collection also found its way into the museum in the form of nickel and iron ore.

But perhaps, Safford’s most enduring legacy lies in his commitment to fieldwork and exploration. Beyond the confines of the classroom, Safford devoted himself to cataloging geographical features underneath the “Nashville Dome.” This geological undertaking, initiated before the Civil War and completed in 1869, proved monumental in differentiating and classifying the three major geologic zones in Tennessee. Furthermore, Safford conducted extensive investigations into mineral deposits, particularly in the Wells Creek Basin in Cumberland, Tennessee, believed to be a meteor crater. From 1889-1891, he meticulously detailed the composition of these deposits. For example, one of Safford’s field notebooks depicts the location and presence of chert, Niagara marble, and Heldenberg rocks in one bluff wall. Collaborating with his student, W.T. Lander, Safford produced a manuscript titled Circumferential Faulting Around Wells Creek Basin, Houston, and Stewart Counties, Tennessee. These field expeditions not only imparted valuable methodologies to others in the field but also laid the foundation for scientists to unravel Earth's geologic history and understand the environmental factors shaping life over millions of years.

Concurrently, amidst his teaching commitments, Safford shouldered significant responsibilities on the Board of Health. His multifaceted roles included membership on the Executive Committee and addressing issues with the water supply, the smoke nuisance, and topography. Moreover, he undertook the task of monitoring the sanitary conditions of the state penitentiary. He also was appointed Census Assistant to Prof. F. W. Hildegard, tasked with compiling a comprehensive report on cotton production in Tennessee. In 1888, Safford studied gas deposits and the efficacy of oil wells predicting their potential advantages for Nashville's future. During this tour, he and his team also discovered iron ore deposits and their utility similar to that of Sequatchie ore. Through this endeavor, Safford's insights extended beyond agriculture, illuminating the intricate connections between topographic changes, public health, water supply, and mineral resources.

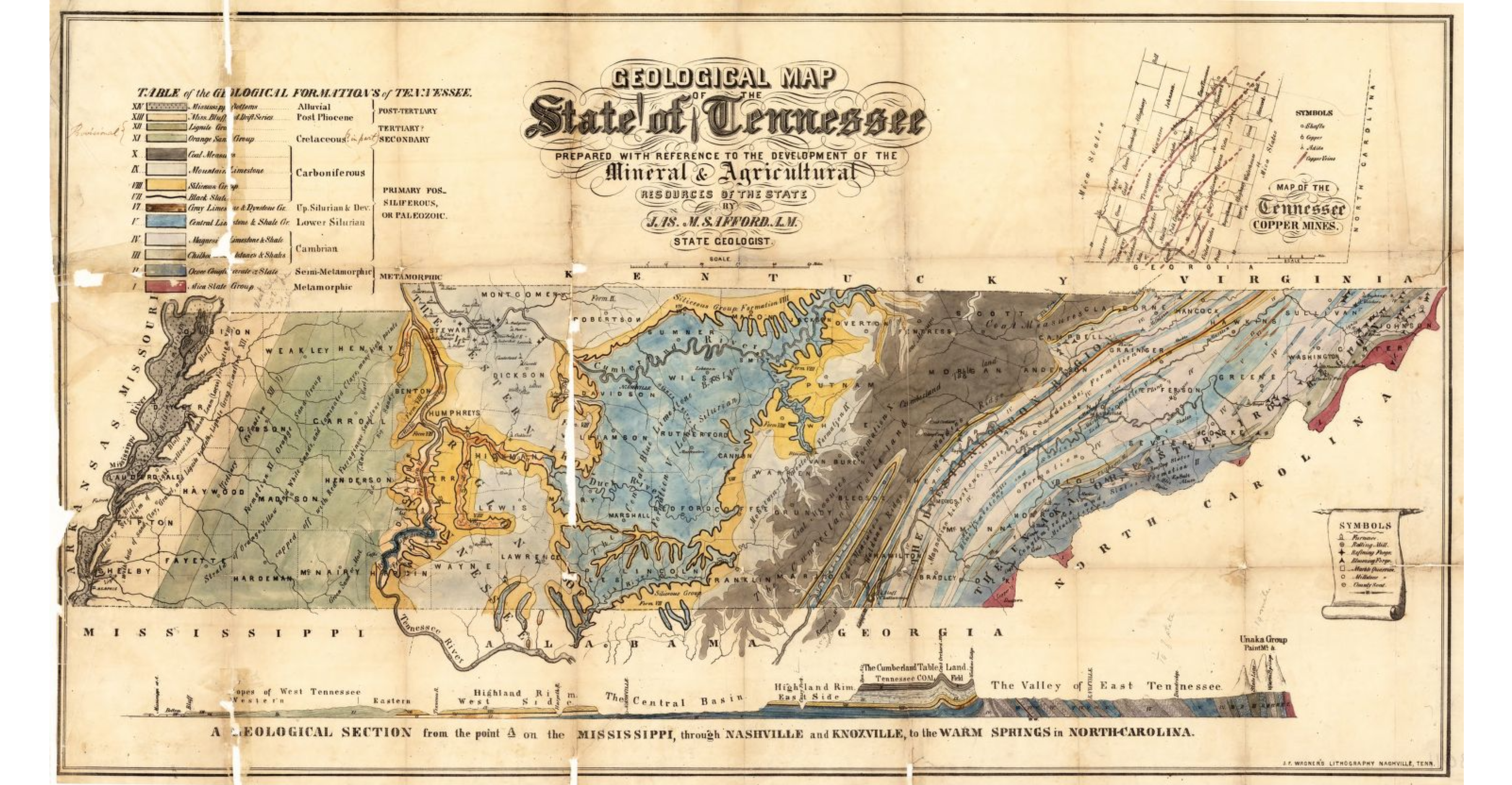

Upon reviewing historical records, the full extent of Safford’s influence became evident. Safford's influence extended far beyond the confines of Vanderbilt. His most notable works, The Resources of Tennessee and The Elementary Geology of Tennessee served as foundational texts for generations of students and researchers, while his tireless efforts as State Geologist, Board of Health member, and his Geographical Map of the State of Tennessee, Prepared with Reference to the Development of the Mineral & Agricultural Resources of the State for the Tennessee Centennial Exhibition in 1897, laid the groundwork for understanding Tennessee's topographical, mineral, and agricultural inner workings. So much so that a Nashville Banner article from 1895, summarized Professor Safford’s contributions as such, “He took hold of the state when nobody knew its resources.”

In 1889, in an article for The American (now The Tennessean), researcher A.T. Ramp commended Safford's geological insights, advocating for better support for his work. Ramp highlighted Safford's expertise and emphasized the importance of adequately funding geological surveys for future progress. Safford’s legacy cemented the importance of geology in league with other scientific fields of the time. Such a legacy was found in two doctoral students in the field of geology — Paul McConnell Jones and Calvin Smith Brown — both of whom earned their degrees under Safford in 1892. Jones’s notable work, The Geology of Nashville, included a geological map of Nashville and connected thesis, which Safford supervised.

Shortly after, on June 6th, 1900, Safford resigned from Vanderbilt University due to old age after teaching there for twenty-five years. Yet, his retirement was marked not by accolades but by the profound respect and admiration of his peers. Chancellor Kirkland praised Safford's contributions, citing his long-standing service, scientific eminence, teaching success, and admirable character, which earned him esteemed recognition among his fellow professors upon retirement. Notably, Safford became the final original Vanderbilt faculty member to resign in 1900, subsequently becoming the first professor to receive the honor of Professor Emeritus from Kirkland.

In his final letter, sent on May 20th, 1905, Safford mentioned his list of publications and wrote, “If I live long enough and have the strength I expand to add to this. But I am not strong and may fall away any day.” By the time he died in 1907, Safford had completed 100 books, publications, and reports — all geared toward enriching the future generation of geologists. He was 84 years old.

By: Ashley Rogers, Evolutionary Studies research assistant

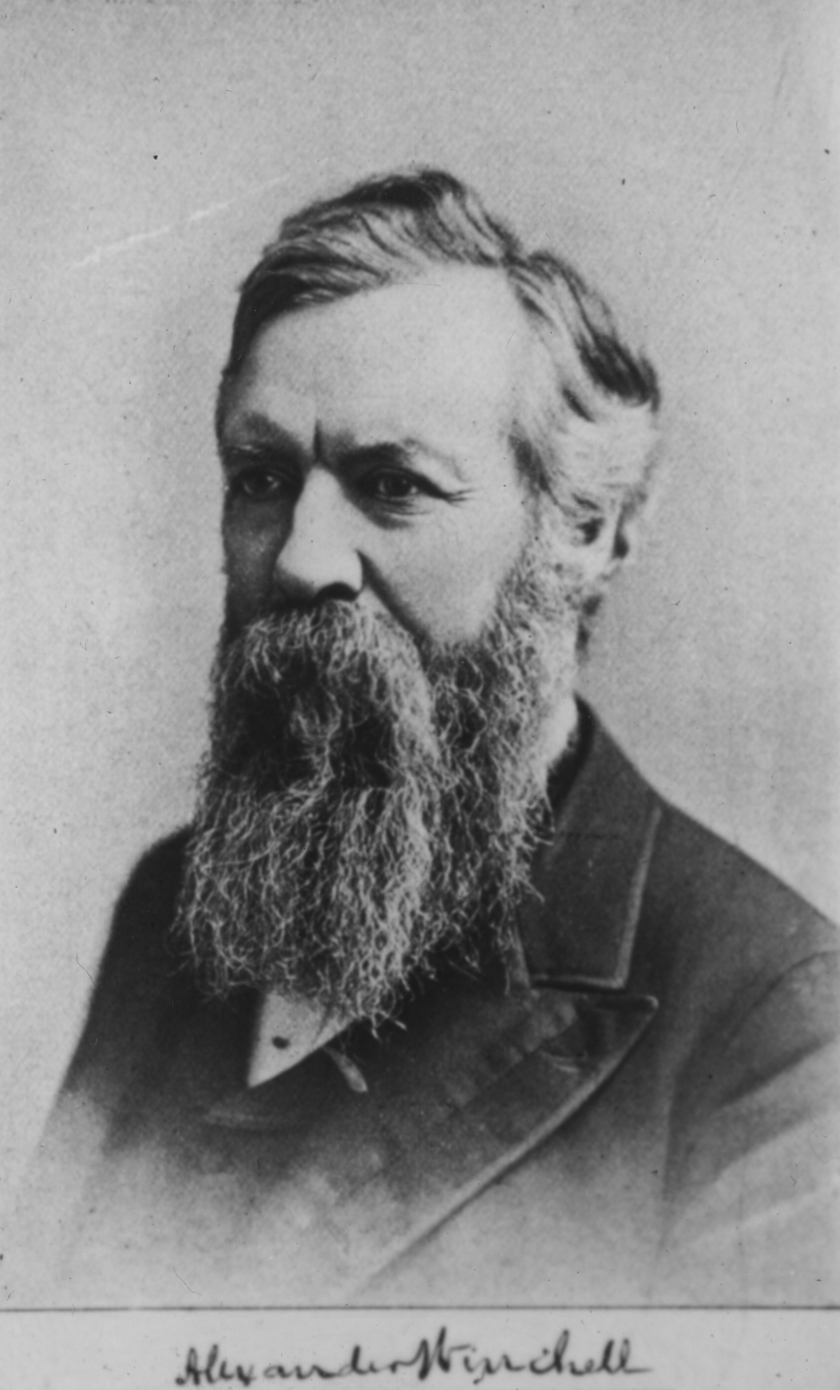

Alexander Winchell, also commonly referred to as the “Great American Geologist,” was a well renowned geologist in the late 19th century. Winchell was born on December 31, 1824 in North East, New York. He attended Wesleyan University and graduated in 1847. Also, in 1850, he earned a M.A. degree. He taught at various universities including in Selma, Alabama, at the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor, Syracuse University, and Vanderbilt University. At the University of Michigan, he was initially a professor of Physics and Civil Engineering. He later switched to teaching Geology, Zoology, Botany and Paleontology and continued to teach these subjects at Syracuse and Vanderbilt.

Winchell was a Geology professor at Vanderbilt University from 1875 to 1878. He was heavily sought after by Bishop Holland McTyiere who was very familiar with Winchell’s reputation at other universities. After finally agreeing to teach at Vanderbilt, Winchell obtained the position of the Chair of Natural History and Geology alongside James M. Safford. Many of Winchell’s teachings were influenced by evolutionary thought and theories. Though his work was heavily influenced by evolutionary principles, he opposed Darwin’s theory of evolution by the means of natural selection. He believed that natural selection could only work as a mechanism to refine and make species better adapt to their environment as opposed to having the ability to create new species.

Theories of evolution at the time opposed those of the Southern Methodists; however, written records indicate Winchell was allowed to speak on the subject in his courses. It was not until Winchell wrote a booklet titled “Adamites and Pre-Adamites” that Winchell’s relationship with Southern Methodists at the time became tense. This booklet implied that Black people were the first on this Earth, the Pre-Adamites, and the white majority evolved after the Pre-Adamites were already established on Earth. At the time that this was written, Black people were viewed as inferior humans who were stripped of their humanity by the white majority. As a result, this booklet received a lot of backlash, as it implied that Black people paved the way for the white majority and were the first to establish life on Earth. It was also viewed in a negative light because it conflicted with the Biblical story and identity of Adam and Eve in the Bible, as argued by the Southern Methodist majority.

Consequently, after writing this booklet, Winchell was dismissed from Vanderbilt and his full responsibilities were transferred to his co-chair James Safford. Though Winchell created this booklet and was beloved by a lot of different universities at the time, he was not absent of racist beliefs and teachings. He commonly referred to Black people as people who “could not be held to the same standard as the white man” and described the ways in which Black people were “phenotypically inferior” to the white man. These views were accepted at Vanderbilt as they aligned with many of the ideals that the Southern Methodists of the time preached and were heavily ingrained in societal norms of the time. However, as soon as Winchell implied that Black people in some way were superior to the white majority (like, by evolving first), he was no longer in alignment with the Southern Methodists’ thought, and his science as well as reputation at Vanderbilt were at stake.

We wrote a short story with images from the VU Media Database and cartoons created in Magic Media AI. Check it out here!

From the Nashville American, July 2nd, 1899, the day after Dr. Jones drowned off the coast at Woods Hole.

Dr. Jones was an Alabamian by birth, the son of Col. John A. Jones, of the Confederate Army. He was born near Camden, Wilcox County, in 1867, and his early boyhood was spent near this town. His mother was Miss Mary Scott, of Tuscaloosa, a sister of Mrs. W. J. Vaughn and Mrs. R. K. Hargrove. When 16 years of age Dr. Jones come to Nashville to live with Dr. Vaughn, and two years later, in 1885, he entered Vanderbilt. As a student he was of indomitable energy, and when he graduated in 1889 his scholarship record was second only to that of Dr. Merriam, his bosom friend and companion, who was drowned several years ago in Lake Cayuga, near Cornell university. Dr. Jones took an active part in athletics in the university, and held several records in field sports for a number of years. He was a member of the Phi Delta Theta Fraternity.

After graduation, Dr. Jones continued his studies in the university, making a specialty in mineralogy and biology. He received his degree of M. S. in 1891 and was elected to sub-professor of mineralogy and biology at Vanderbilt, which position he held until last year, when he was elected adjunct professor of biology and lecturer on embryology in the medical department. In 1892 he took the degree of D. Sc. At the time of his death he was a member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and of the Engineering Association of the South. He was also an assistant geologist in the United States Geological Survey from 1890 to 1891, and was connected with the Marine Biological Laboratory from 1891 to 1895.

While an indefatigable worker in the performance of his university duties Dr. Jones was an ardent patron of college athletics and devoted considerable time to the promotion of clean athletics. He has been Secretary of the Vanderbilt Athletic Association for a number of years and was also Secretary of the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association. He was of a quiet, companionable disposition and won friends in every work with which he was connected. he has been a leading spirit in the college life of Vanderbilt and was known more widely, perhaps, than any other man who was ever connected with the university. He was also well-known in Nashville, and was a general favorite in all circles in which he moved.

It is a remarkable coincidence that Dr. Jones should have met the same fate which befell his classmate and chum, Dr. Merriam. The latter’s sad end made a profound impression on him which he was never able to overcome. It was recalled by members of Dr. Vaughn’s family that just before his departure for Woods Hole Dr. Jones remarked half jocularly that if he should be drowned on the trip he had made all arrangements for the disposition of his effects. The premonition, though indirectly expressed, showed the trend of his mind on the subject.

At Woods Hole, where Dr. Jones was drowned, there is located a United States marine biological station, and for two summers past he has been attending the summer school conducted there by Dr. C. A. Whitman, of Chicago University. As Dr. Jones was a man of fine physique and a good swimmer it is presumed that he was seized with a cramp and so drowned.

Besides the legion of friends who will mourn his untimely end, Dr. Jones leaves a mother, who lives at Asheville, N.C., and four brothers, including E.S. Jones, who graduated at Vanderbilt last month, and Herbert Jones, who is still a student at Vanderbilt.

By: Kaitlyn Russell, Library Buchanan Fellow

Early Life

Early Life

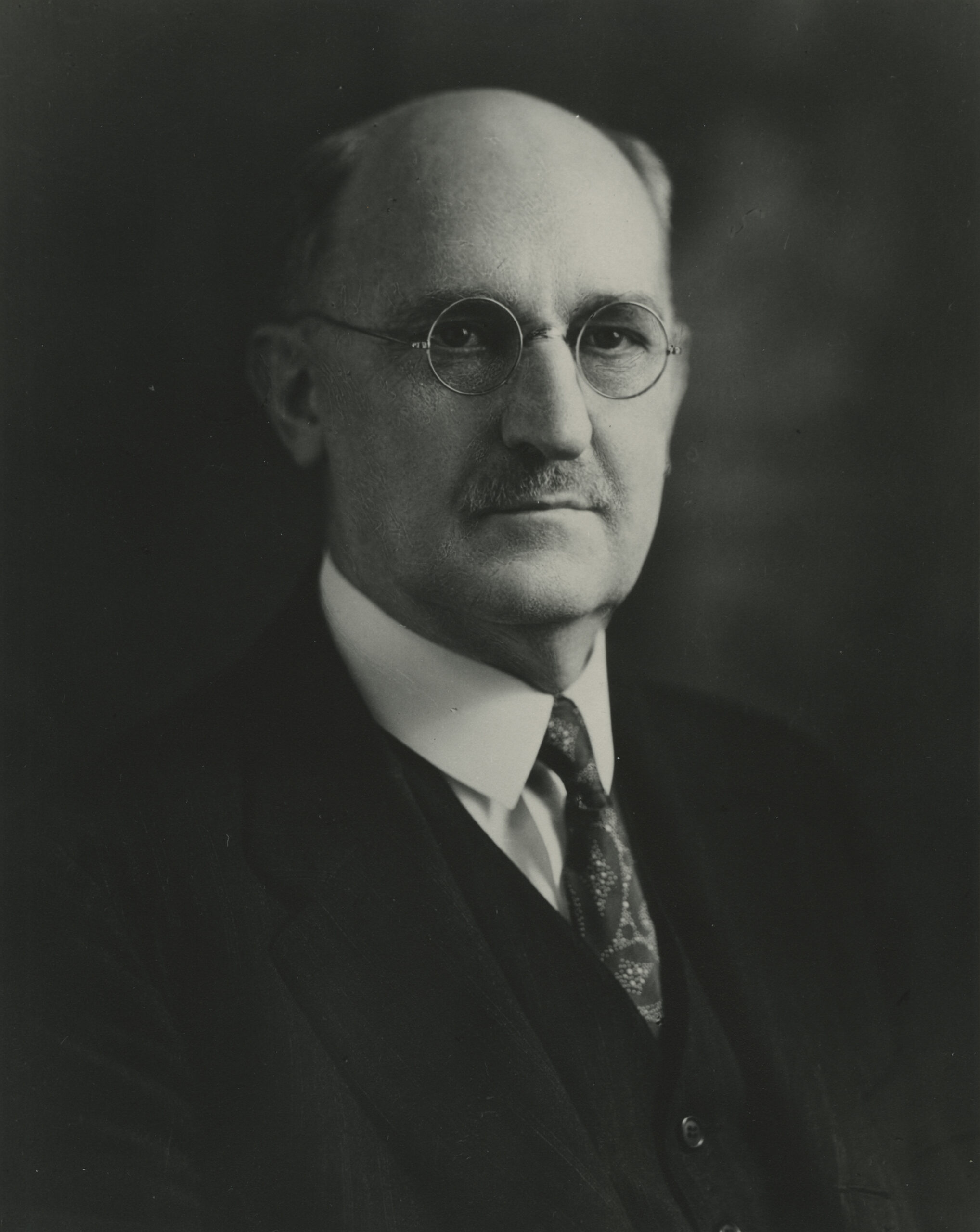

Dr. Leonidas “L.C.” Chalmers Glenn was born in North Carolina on September 9 th , 1871. He earned his bachelor's degree at the University of South Carolina in 1889 and he went on to be the superintendent of grade schools in South Carolina while earning his Ph.D. in geology at Johns Hopkins University. In 1896 he took on advanced work in stratigraphy and paleontology of the Tertiary deposits of the Atlantic Coastal Plain, which earned him his Ph.D. in 1899.

Career

Glenn joined Vanderbilt as an assistant professor in geology in 1900 and became chair of the department in 1903. In 1900, he married Nellie Louise McCullough and the pair had two sons. At Vanderbilt he was the lone geology faculty member for 22 years. He would go on to teach General Geology, Mineralogy, Economic Geology regularly while teaching Invertebrate Paleontology, Advanced Paleontology, and Optical Mineralogy and Petrology occasionally. In 1912, Tennessee was one of the first states to maintain any considerable geological survey due to the work of Dr. Glenn. He went on to publish numerous papers such as The Growth of Our Knowledge of Tennessee Geology in 1912. It was the first comprehensive work of its time for geology in Tennessee. The paper gives the history of all the geology work that has been conducted in Tennessee up to 1910. In 1910 Dr. Glenn also conducted and wrote a paper on the deconstruction of South Carolina forests and in 1904 his work on Miocene pelecypods for his Ph.D. was published by Maryland Geological Society. He published many papers on water resources in Tennessee and coal deposits. In total Glenn published 49 papers, 35 of which were printed before 1918. He was a founder of the Tennessee Academy of Science and served as its president on three occasions. He also served a short time as the Tennessee state geologist. He did field work in geology for the states of Kentucky, North Carolina, and Tennessee along with the United States Geological Survey and the United States Forest Service, including working on coal steams. One place that he investigated was the Appalachian Mountains which showed great erosion. In 1926 he published the geology of the proposed Great Smoky Mountain National Park and due to his extensive knowledge of erosive processes and steam dynamics he was hired in 1919 as an expert witness for the United States Justice Department on the Red River boundary dispute between Texas and Oklamahma. The dispute went to the Supreme Court in 1921. In 1923 Physiography was introduced, which became his largest and primary class. In his later career his teaching loads were heavy, including teaching cadets geography during World War II.

Museum and Other Organizations

He was instrumental in founding organizations such as the Tennessee Academy of Science in 1912 and the Vanderbilt Scientific Research Society and was one of the first presidents. In 1925, Glenn and his colleagues at Tennessee Academy of Science were in support of John Scopes in the Scopes v. Tennessee trial and took a public stand against the Anti-Evolution Act. He was chairman of numerous committees, including the Library Committees, Athletic Committee, Peabody Affiliation Committee, and the Heath Services Committee. In 1935 he was a member of the Board of Consultants of Tennessee Valley Authority. Some other organizations he was a part of include, being the chairman of the boys work department for the Y.M.C.A. and a member at the Old Oak Club. He was also the representative of Vanderbilt in the Tennessee College Association, and the official curator of the museum at Vanderbily. Glenn made enormous contributions to the museum. He added several mastodon bones from and arranged one of the large contributions to Vanderbilt from Gates Phillaps Thurston, who gave the museum Native American artifacts, gems, and minerals. Some artifacts came from the ruins of Pompeii, amongst other places.

Retirement

Glenn retired at 70 years old in 1942, but still continued to come into the department spending his time on collections, especially the Thruston collection for the museum. He worked at Vanderbilt for 42 years. The Alumnus published an article stating that it was one of the greatest and largest geology libraries in the South. At 79, Glenn died in January of 1951.

By: Nick McCoy, Evolutionary Studies undergraduate communications assistant

According to Edward Eustace Reinke, a celebrated biologist, “Everywhere runs the thread of evolution, a unifying principle which explains and leads to new truths and fuller understanding.”

This philosophy guided Reinke’s teachings, including his 30-year career at Vanderbilt University in the mid-1900s and scientific research publications. Reinke frequently advocated for teaching evolution in the classroom and made significant contributions to enhancing the reputation, opportunities, and instruction of biology, natural sciences, and pre-medical courses at Vanderbilt.

This philosophy guided Reinke’s teachings, including his 30-year career at Vanderbilt University in the mid-1900s and scientific research publications. Reinke frequently advocated for teaching evolution in the classroom and made significant contributions to enhancing the reputation, opportunities, and instruction of biology, natural sciences, and pre-medical courses at Vanderbilt.

Education and Contributions at Vanderbilt

Reinke was born on June 27th, 1887 in Jamaica, West Indies. Reinke’s educational journey began at Moravian Preparatory School. He then attended Lehigh University and received a B.A. degree in 1908, and later a M.A. degree. After leaving Lehigh, Reinke obtained a Ph.D. in philosophy from Princeton in 1913. Reinke remained a Biology fellow there from 1909-1913. Reinke became a biology instructor for 1 year at Rice Institute in Texas while also serving as a Research Associate at the Department of Marine Biology at Carnegie Institute from 1912-1915.

Starting out at Vanderbilt University in 1915, Reinke was an assistant biology professor until he became a full-time Professor of Biology in 1922. He taught courses like Biology 1 and 12, with some of these courses focusing on Zoology. In addition he taught Vert. Anst. & C. (lecture and lab), General Embryology & History, and Dietetics. Eventually, Reinke became the Head of the Biology Department. Courses across the department utilized Bayliss’ General Physiology for at least 8 years. In addition, Reinke emphasized the importance of this text in pre-medical student learning and the development of an “analytical mindset” in both the natural sciences and in pre-medical education.

Transforming the Vanderbilt Biology Department

By the time Reinke took the reins, The Department of Biology had evolved from the Department of Natural History and Geology. This department was formerly headed by James M. Safford, followed by Paul M. Jones, until Natural History and Geology separated in 1898. While Reinke served in this role, other professors ignited discourse on the further separation of the Biology Department to become the Department of Botany and the Department of Zoology, respectively. At the onset of this debate, Reinke asked himself if “biology shall be divided?” However, Reinke ultimately voiced opinions against this change due to several reasons: there was a low interest in botany, Vanderbilt was not an agricultural school, and the division would lead to many shifts in faculty, courses, and resources. Reinke’s list of eventual compromises to this decision included — “adding ecology, bacteriology, and genetics to the zoology curriculum,” a further discussion on plant and animal life across all courses, and Reinke wanted to ensure that if the department were to split he would remain the Head of the Biology Department. Reinke would later become The Director of the Biological Sciences.

The Building of Buttrick Hall & Campus Involvement

Reinke was also the driving force behind moving the department and overseeing the construction of Buttrick Hall. The purpose was to create a biological laboratory that was suited to the size of Vanderbilt. Starting in 1925, Reinke and other collaborators planned to have a Department of Botany and a Department of Zoology, where 64 students could be a part of the botany laboratories and 96 students in geology could learn inside Buttrick Hall on Vanderbilt’s campus.

Elsewhere on campus, Reinke assumed the role of Secretary of the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences in 1923, where he took on many responsibilities in carrying out administrative and organizational duties of the department. The role included a great deal of work: reordering the sequence of classes for students in the department and making sure students had a variety of academic experience and understandings. By 1941, Chancellor O. C. Carmichael had also appointed Reinke to the Curriculum Committee and to serve as a member of the Committee on Educational Policies. Reinke also worked as the Chairman of the Division of Natural Sciences and Mathematics to provide more opportunities and clearer requirements for transfer students and current undergraduates to enter the School of Medicine. For example, Reinke campaigned for a petition to provide financial scholarships to Davidson County students who had excelled at Vanderbilt and were in need of financial aid. Due to Reinke’s investment in students like Ray Womack ‘93, Womack was able to return to campus to finish out his degree. Womack went on to receive his M.D. from Vanderbilt in 1945 and served as a Resident Physician at Vanderbilt Hospital. Additionally, Reinke received funds from the General Education Board of the Rockefeller Foundation for research and scholarships in the natural sciences.

Elsewhere on campus, Reinke assumed the role of Secretary of the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences in 1923, where he took on many responsibilities in carrying out administrative and organizational duties of the department. The role included a great deal of work: reordering the sequence of classes for students in the department and making sure students had a variety of academic experience and understandings. By 1941, Chancellor O. C. Carmichael had also appointed Reinke to the Curriculum Committee and to serve as a member of the Committee on Educational Policies. Reinke also worked as the Chairman of the Division of Natural Sciences and Mathematics to provide more opportunities and clearer requirements for transfer students and current undergraduates to enter the School of Medicine. For example, Reinke campaigned for a petition to provide financial scholarships to Davidson County students who had excelled at Vanderbilt and were in need of financial aid. Due to Reinke’s investment in students like Ray Womack ‘93, Womack was able to return to campus to finish out his degree. Womack went on to receive his M.D. from Vanderbilt in 1945 and served as a Resident Physician at Vanderbilt Hospital. Additionally, Reinke received funds from the General Education Board of the Rockefeller Foundation for research and scholarships in the natural sciences.

Throughout his tenure, Reinke had to navigate the complex challenges of leading students and staff amidst the turmoil of world wars. Reflecting on World War 1, Reinke noted, “I have been as busy as can be of course. I’ve lost time with my class (influenza attack). Ordinarily I have an instructor and a graduate assistant but neither could be obtained this year. The Government gave us a unit of the Student Army Training Corps or SATC (...) boys below twenty-one entered college.” This turned parts of campus into learning centers for the SATC. During the 1940s, Reinke often had to find replacements for professors and colleagues. For instance, when Dean Pomfret joined World War II, Reinke had to find a replacement in Vanderbilt’s Senior College of Arts and Science Graduate School. Reinke eventually came to serve on the Executive Council for the Graduate School as well, where he continued to campaign for educational access and research grants for graduate students.

Advocacy for the Teaching of Evolution

During Reinke’s teaching career, the primary challenge he faced was the national and Tennessee-specific debate and legislation banning the teaching of evolution in schools. The teaching of evolution — as outlined by Charles Darwin — was sought to be banned by the anti-evolutionist movement enacted by the Tennessee House of Representatives member John W. Butler. The Tennessee Legislature on March 13th, 1925 passed The Butler Act or alternatively — the The Evolution Bill — “an act prohibiting the teaching of the evolution theory in all the universities, normals, and other public schools of Tennessee (...) where any teacher found guilty of a violation of this act, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon conviction shall be fined not less than $100 nor more than $500 for each offense.” Although Vanderbilt was relatively protected under the new legislation due to their private status, Reinke wanted to ensure his stance on the issue was not misconstrued regarding the restrictions of teaching evolution and surrounding the foundation of religious or moral trust on campus.

In one speaking engagement with many Vanderbilt Alumni in attendance, Reinke openly responded to these recent laws, by saying the current state of evolutionary discourse is in “intellectual mire” where there is an entanglement of sorts surrounding the understandings and teachings of evolution, particularly within the state of Tennessee. In a newspaper clipping, Reinke addressed organic evolution and stated that evolution was not present in a standalone course offered at Vanderbilt. According to course catalogs, 4 total (Biology 1, 11, 12, and 18) courses, at the time, taught it explicitly. Reinke succinctly states that “The test of Christianity comes from (...) truth in the hearts and minds of men, truth revealed by the microscope and the telescope.” This sentiment echoed Reinke’s belief that the teaching of evolution is a necessary component of all students’ education.

In one speaking engagement with many Vanderbilt Alumni in attendance, Reinke openly responded to these recent laws, by saying the current state of evolutionary discourse is in “intellectual mire” where there is an entanglement of sorts surrounding the understandings and teachings of evolution, particularly within the state of Tennessee. In a newspaper clipping, Reinke addressed organic evolution and stated that evolution was not present in a standalone course offered at Vanderbilt. According to course catalogs, 4 total (Biology 1, 11, 12, and 18) courses, at the time, taught it explicitly. Reinke succinctly states that “The test of Christianity comes from (...) truth in the hearts and minds of men, truth revealed by the microscope and the telescope.” This sentiment echoed Reinke’s belief that the teaching of evolution is a necessary component of all students’ education.

Reinke was a champion of evolutionary educational rights. At this event and at many others, Reinke shared his ideas and confidence in science. Reinke continued to make intentional changes about how evolution was placed into courses and curriculum at Vanderbilt. Based on archival correspondence with Dr. G. Canby Robinson, Dean of the Vanderbilt Medical School throughout the 1920s and chairman of the Department of Medicine, Reinke suggested that Biology XIII should cover mammalian anatomy, avian, and mammalian embryology, and then bacteriology in the third term to better prepare pre-medical students for future coursework. Using many of the administrative and scientific resources at his disposal, Reinke urged many to continue the teaching of evolution in schools, his beliefs could be summarized by a question asked at that Vanderbilt Alumni meeting — “march down the highway of intellectual progress or wade around in the slog of ignorance?” Reinke's rhetorical efforts did not lead to an immediate overturn of the legislation. Although the Butler Act was passed in 1925 and led to the notable Scopes trial that same year, bringing national attention to the debate over teaching evolution, the act was not repealed until 1967.

Research Contributions and Publications

Not only did Reinke serve in the multifaceted roles listed above at Vanderbilt, but he also contributed to many scientific publications related to hormones, cytology, and vertebrate embryology evolution. Research occurred when Reinke became Director of the Highlands Museum and Biology Laboratory beginning in 1929 in North Carolina and later, during his work as a research associate at the Dry Tortugas Laboratory. In April 1925, a large volume of publications titled Cytology which entails the understanding of the special problems connected with the life and growth of the cell. Reinke’s work The Development of Apyrene Spermatozoa of Strombus Bitubercula investigated sperm dimorphism in the prosobranch sea snails.

According to the Journal of Experimental Zoology, Reinke’s work on Triturus viridescens, a U.S. newt species, spends part of its life cycle in water and then transition to living land. These newts called ‘red efts’ shed the red skin during their terrestrial phase as they mature, transitioning to a green coloration in adolescence — as mentioned in Time magazine. Reinke and Claude Simpson Chadwick of Vanderbilt and Highlands Laboratory wanted to answer the question: What impels them, after so long a time on land, to go back to the water? In this venture, the duo implanted bits of adult pituitary gland in their muscles, and the North Carolina newts went into the water and quickly assumed their adult form. Their findings indicated that “the pituitary provided not only the necessary physiological changes for aquatic life but also the ‘water drive’ or impulse to seek water.” Sex glands and thyroid removal also occurred to test their ability to influence newts' evolution back into the water. The results proved that only the pituitary gland could influence this development for adolescent newts.

At one of the meetings of the Southeastern Biologists, Reinke presented this research on the relation of hormones to the amphibian life cycle. The next meeting was held at Vanderbilt in April of 1939. During the conference Reinke additionally campaigned for the establishment of a summer laboratory in the southern Appalachians that would greatly improve a variety of biological investigations. A mountain station would offer splendid opportunities in taxonomy, in ecology and in studies on adaptation of organisms.

Legacy and Impact on Evolutionary Studies

Dr. Reinke held several notable positions, including being a member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the American Society of Zoologists, the Association of Southeastern Biologists (where he served as president from 1933 to 1939), and the American Association of Anatomists; all while being a dedicated member of the Vanderbilt community since 1913. Dr. Reinke resigned in 1935. Reinke’s work cemented him as a crucial figure in the history of evolution at Vanderbilt, his philosophies led the way for how evolution was taught across the college. Based on a 1925 newspaper clipping, Reinke declared that educators should “Teach evolution with heart.” Reinke’s body of work was a testament to that message. At 57 years old, Reinke died on Jan. 25th, 1945.

By: Bill Xu, Library Buchanan Fellow

Willard Brownell Jewell was born in Little Compton, Rhode Island on April 4, 1899. He graduated from Mount Harmon School for Boys in 1918. He served as a seaman in U.S. Navy from September to December in 1918 and Ships Carpenter in U.S. Merchant Marine from February to August in 1919.

Willard Brownell Jewell was born in Little Compton, Rhode Island on April 4, 1899. He graduated from Mount Harmon School for Boys in 1918. He served as a seaman in U.S. Navy from September to December in 1918 and Ships Carpenter in U.S. Merchant Marine from February to August in 1919.

He finished his degree at Brown University in 1923. A few days before his graduation from Brown, he was told about an opening in the geological field, so he went to Canada and became a geologist. Jewell finished his Ph.D. at Princeton University in 1925.

After his graduation, he moved to Vanderbilt to become an assistant professor. He was promoted to associate professor in 1938. He also worked as a visiting professor of geology at Colorado College in the summer of 1935, and director of the Vanderbilt Summer Field Trip in Geology in 1929, 1930, and 1936. He remained at Vanderbilt, where he was promoted to full professor and chairman of the Department of Geology in 1942. He eventually became dean of the Geology department.

Jewell focused his research on the mineral deposits and geology of Alaska, British Columbia, Tennessee, and Newfoundland. During World War II, he volunteered to learn meteorology so that he could teach the subject to cadets in the Army, according to Professor Emeritus Leonard Alberstadt. Jewell died in 1969.

By: Carly Stewart, Library Buchanan Fellow

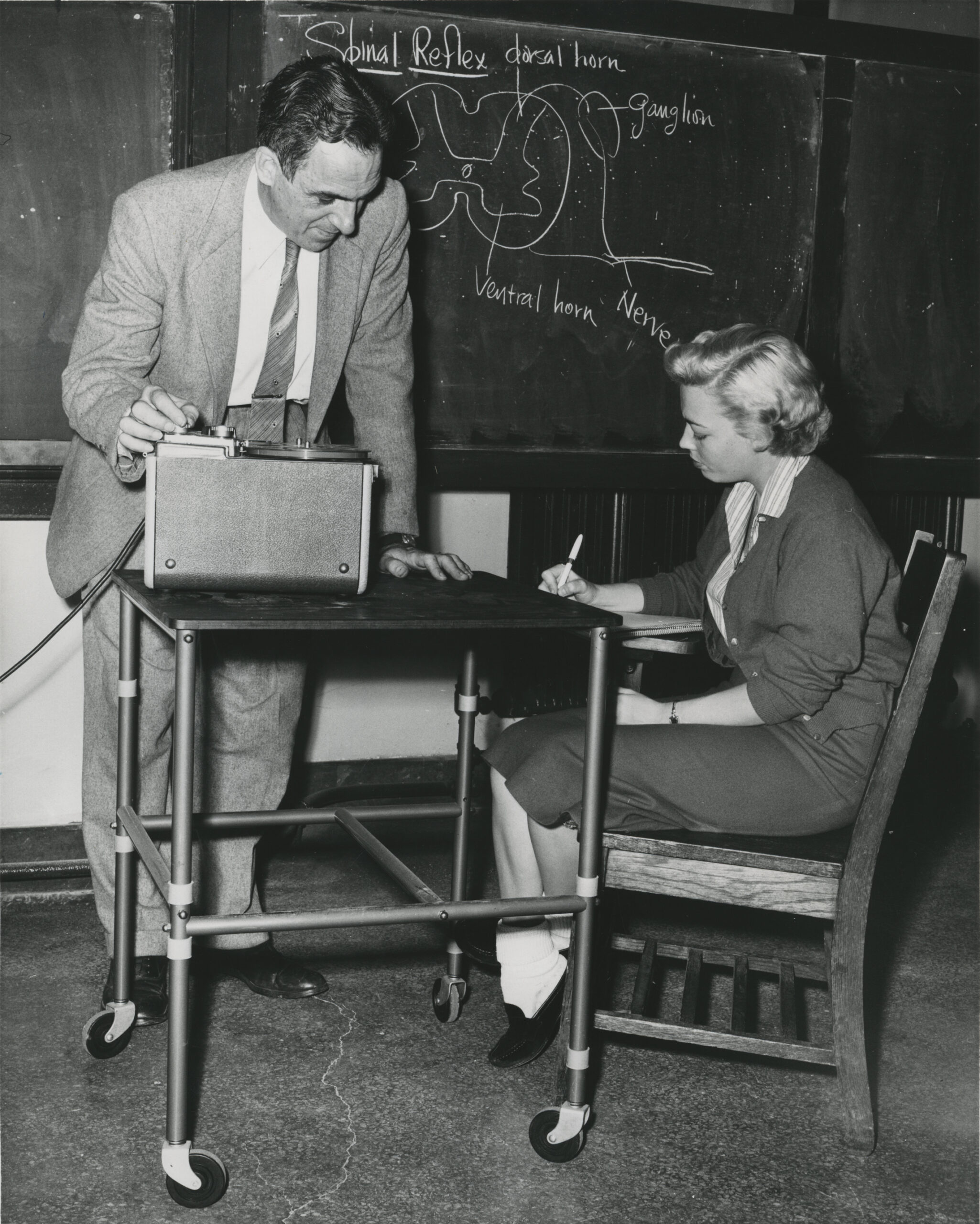

Dr. Claude S. Chadwick was born in 1907 and is originally from Carthage, Texas. He received a B.S. degree from Centenary College in Louisiana, and an M.S. degree at Vanderbilt University. After graduating, he spent some time working at the University of Michigan, before joining the Vanderbilt biology department in 1927 as a teaching fellow and instructor while he worked toward his Ph.D. under Dr. Edward Reinke. He became an assistant professor in 1939. He was subsequently sworn in as a lieutenant in the US Naval Reserve in 1944, serving on the SS Thomas during World War II. Upon his return to Vanderbilt in 1946, he became an associate professor, and a full professor at Peabody College in 1951. In 1963, he left for Emory and Henry College.

Dr. Claude S. Chadwick was born in 1907 and is originally from Carthage, Texas. He received a B.S. degree from Centenary College in Louisiana, and an M.S. degree at Vanderbilt University. After graduating, he spent some time working at the University of Michigan, before joining the Vanderbilt biology department in 1927 as a teaching fellow and instructor while he worked toward his Ph.D. under Dr. Edward Reinke. He became an assistant professor in 1939. He was subsequently sworn in as a lieutenant in the US Naval Reserve in 1944, serving on the SS Thomas during World War II. Upon his return to Vanderbilt in 1946, he became an associate professor, and a full professor at Peabody College in 1951. In 1963, he left for Emory and Henry College.

Chadwick researched hormones using newts as a model organism, studying aspects such as their life cycle. He published at least four scientific articles while at Vanderbilt. One of his experiments, which determined that the pituitary gland is responsible for a newt’s impulse to seek water, was featured in Time Magazine in 1940. Chadwick was a member of professional organizations including the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine, the Association of Southeastern Biologists, and the Tennessee Academy of Science. He gave a variety of lectures, including “Man, the Becoming Species,” “Time’s Arrow and the Genes,” and “In His Image,” the latter of which was likely part of a church speaker series titled the Lenten Forum Series.

He also presented a lecture during the series “Great Human Issues of our Times” in 1953. The lecture series was reportedly the first integrated event at Peabody College. However, his beliefs on race were complicated, as he also made uncomfortable remarks about overpopulation in the Nashville Banner. In 1961, he wrote that while he believed the US could support a population up to one billion people, China and India were overcrowded. He also stated that birth control was not the answer, and that modern sanitation prevented the natural order of biology whereby certain conditions and mutations were not meant for survival. By 2026, he said, the world’s population “will be approaching infinity” with too many people being “of the yellow race.” Thus, though Chadwick was a supporter of integration at Peabody, it seems that his views were complicated and still reflected an uncomfortable view of other cultures.

Outside of his scientific career, Chadwick had a rich personal life. He was involved in campus life at Vanderbilt, heading the Camera Club unit of the Vanderbilt Outdoor Club as well as the Vanderbilt University square dance team. He even directed the Vanderbilt Pre-Med Club’s square-dancing team and wrote an illustrated book called “Let’s Square Dance.” He also judged several science fairs in his spare time, belonged to the West End Methodist Church, and was president of the Brotherhood Bible Class.

By: Dante Hernandez, Library Buchanan Fellow

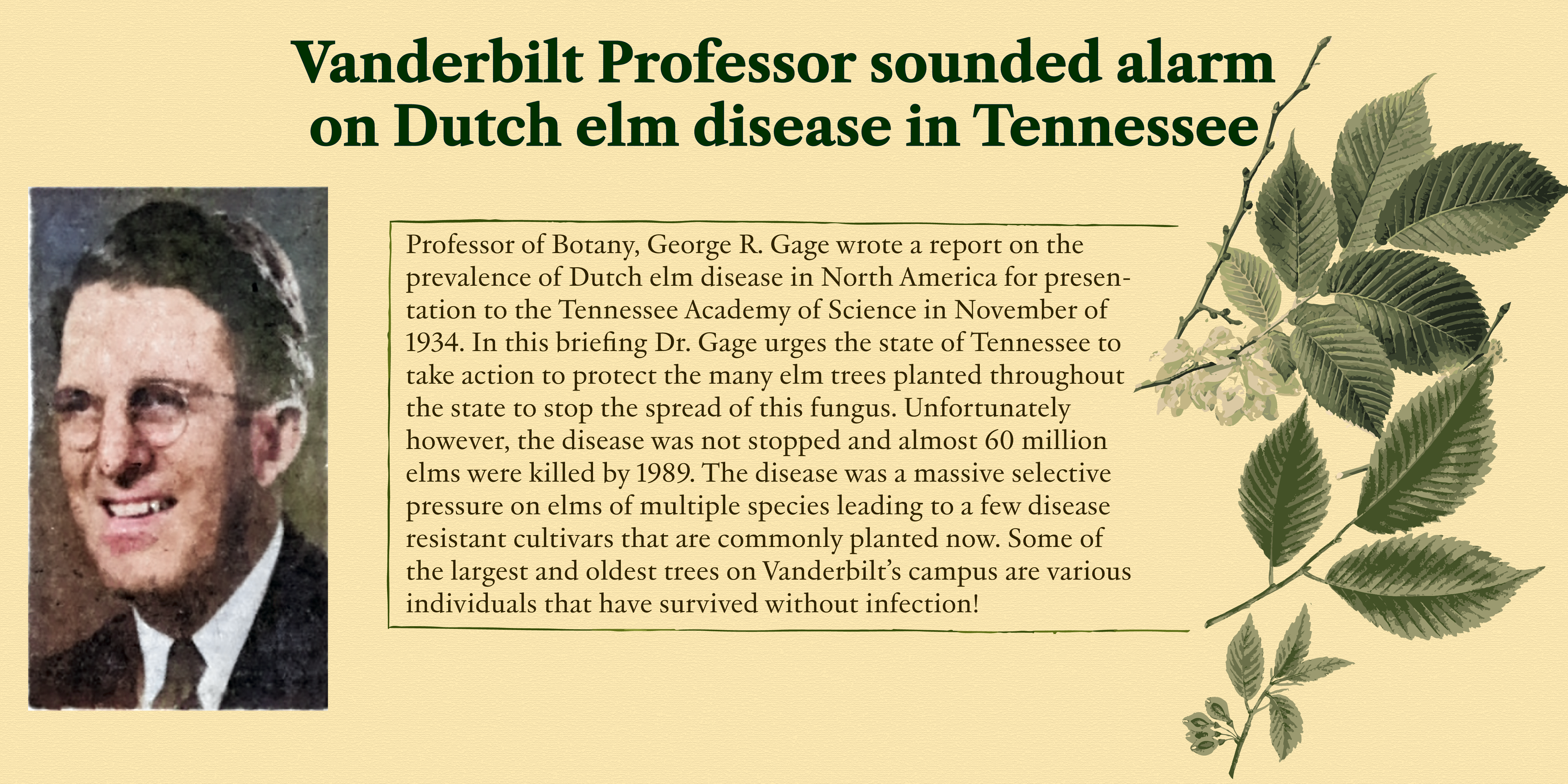

Dr. George R. Gage was a professor of botany born on August 6, 1890, in Atlantic City, New Jersey.

Dr. George R. Gage was a professor of botany born on August 6, 1890, in Atlantic City, New Jersey.

He graduated Pennsylvania State College (now Pennsylvania State University) with a B.S. in 1914, an M.S. from Michigan State College (now Michigan State University) in 1915, and a Ph.D. from Cornell University in 1926, he served in the military during World War II in the Army Air Corps. After teaching at Michigan State College, Cornell University, and DePauw University, he joined Vanderbilt University in 1928. He died in his home of a heart attack on August 18, 1945.

Gage was a plant pathologist who worked on semiloose smut disease of oats for a considerable part of his career with published papers by the Agricultural Experiment Station at Cornell University. While at Vanderbilt, he was one of the few people concerned about the danger that Dutch Elm disease posed to the North American elm tree populations. He warned colleagues of the looming threat in a presentation to the Tennessee Academy of Science in 1934. In this presentation he discussed how the problem could be mitigated but that it would require money that the USDA did not have. Eventually, the disease would go on to wipe out 40 million trees across the North American continent.

Gage also helped found the Vanderbilt University herbarium collection in 1935 with Dr. Harold Bold. The Vanderbilt University collection housed 20,000 specimens before being sent to the Botanical Research Institute of Texas in 1996 for preservation. Currently, the collection is being digitized for use in botanical research across the world.

Gage was also an important advisor to the Vanderbilt Garden Club, students who were interested in learning more about plants and plant improvement. Before professional landscaping was done around the university, the garden club was in charge of all the plantings done on campus. He gave numerous talks to the members on a variety of topics, including the life cycle of pea plants and strategies for improving plant growth and yield.

Gage was also in charge of managing many of the trees during the summer. He spoke many times about how trees should be managed when they are damaged and when tree “surgery” is necessary. He was all around a supporter of ensuring trees are not cut down when possible.

By: Olivia Quiroga, Buchanan Library Fellow

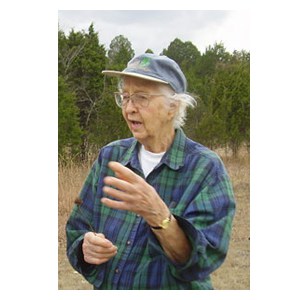

Dr. Elsie Quarterman was a researcher, biologist, botanist, and professor at Vanderbilt University. She joined the Vanderbilt faculty in 1943, teaching during World War II. and eventually became the university’s first female academic department chair.

Dr. Elsie Quarterman was a researcher, biologist, botanist, and professor at Vanderbilt University. She joined the Vanderbilt faculty in 1943, teaching during World War II. and eventually became the university’s first female academic department chair.

Born November 28, 1910, in Valdosta Georgia, Quarterman attended Valdosta High School and earned the A.B. degree in English from Georgia State Women’s College (now Valdosta State University). Quarterman earned her M.A. degree in botany at Duke University in 1941. She completed her Ph.D. under Dr. Henry Oosting in Duke’s botany department, where she focused on plant ecology and wrote her dissertation on the cedar glades of middle Tennessee. She remained close with her advisor throughout her years at Vanderbilt, often leaning on him for professional advice.

Oosting said of her in a letter of recommendation, “Dr. Quarterman is a dedicated and superior teacher. She speaks well under any circumstances, has given much thought to methods and objectives in modern beginning science courses, works conscientiously at improving her courses, and always has the student in mind. That she has attracted several graduate students to continue work with her is certainly indicative of her stimulating influence and the regard with which they hold her.”

She taught systematic botany, plant anatomy, and the year-long series in general botany. She would go on to develop her own plant ecology class and teach evolution as well.

After WW2 ended, the university sought to end the teaching responsibilities of many newly employed women. The chair of the department, however, fought to keep Quarterman on the faculty due to her outstanding botany teaching capabilities. Quarterman became the first woman to serve as an academic department chair at Vanderbilt University in General Biology in 1961. In a 1961 NSF application, she wrote, “the problem of evolution represents one of the great opportunities jointly facing taxonomy and ecology; accordingly, the program at Vanderbilt has been designed to utilize the appropriate concepts and methods of these two disciplines, and indeed any pertinent disciplines, as means of elucidating evolutionary problems.

After WW2 ended, the university sought to end the teaching responsibilities of many newly employed women. The chair of the department, however, fought to keep Quarterman on the faculty due to her outstanding botany teaching capabilities. Quarterman became the first woman to serve as an academic department chair at Vanderbilt University in General Biology in 1961. In a 1961 NSF application, she wrote, “the problem of evolution represents one of the great opportunities jointly facing taxonomy and ecology; accordingly, the program at Vanderbilt has been designed to utilize the appropriate concepts and methods of these two disciplines, and indeed any pertinent disciplines, as means of elucidating evolutionary problems.

Quarterman earned emeritus status in 1976 and died at the age of 103 on June 9, 2014.

The university featured her on vanderbilt.edu/150 as part of their sesquicentennial

celebrations.

By: Andy Flick, Evolutionary Studies scientific coordinator

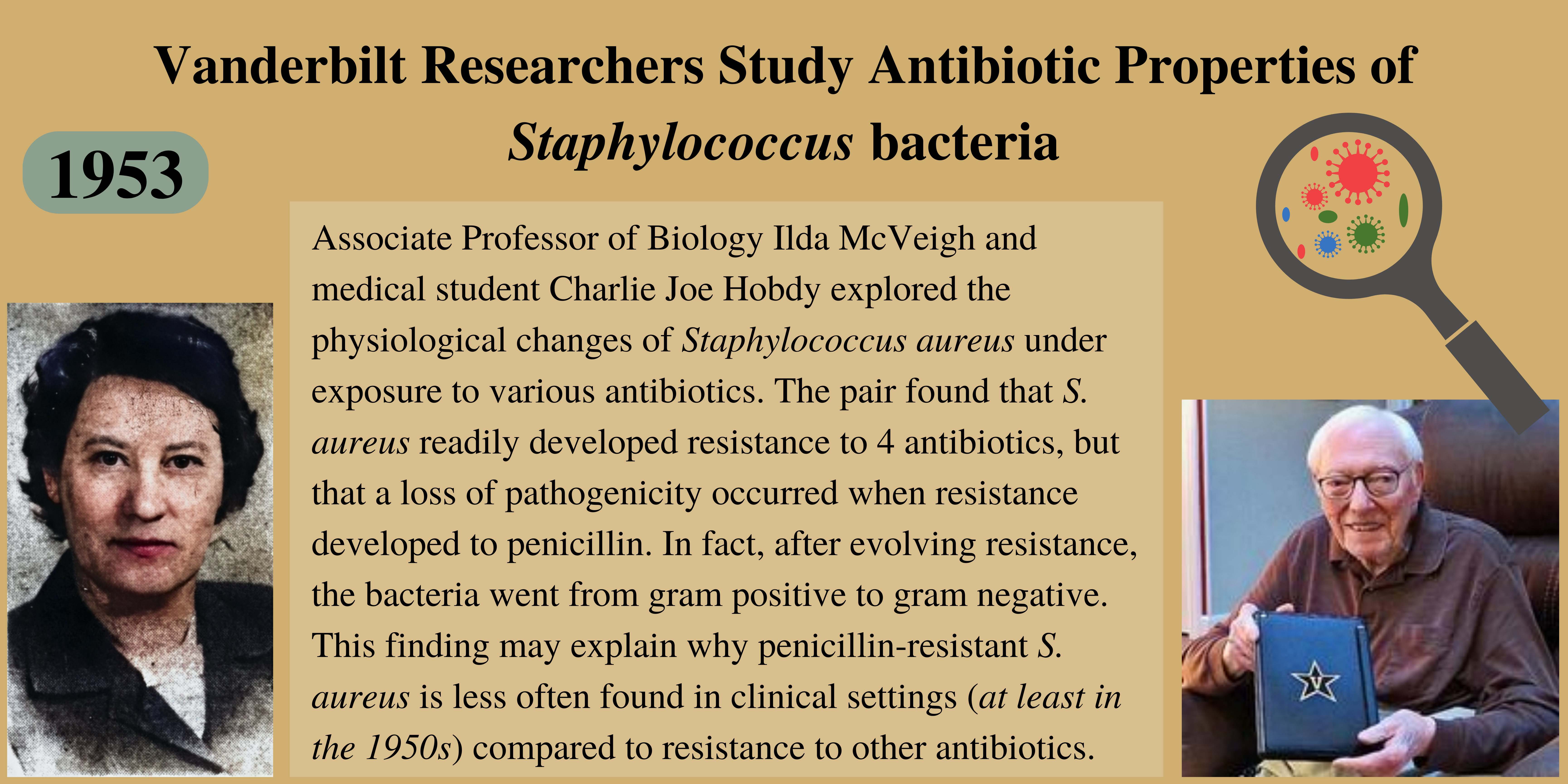

Ilda McVeigh was a biologist at Vanderbilt University from 1948 until her retirement in 1968.

By: Neomi Chen, Evolutionary Studies undergraduate communications assistant

Born on Independence Day in Gallman, Mississippi, Dr. Robert Ben Channell's academic accomplishments were nothing short of extraordinary. As a botanist, Channell's pioneering contributions to the field of evolution, particularly his taxonomic revision of the 'Eu-Rhynchospora' portion of the genus Rhynchospora and groundbreaking research on the genus Trillium, cemented his legacy. At Vanderbilt University, he tirelessly secured grants to enhance the educational experience for both undergraduate and graduate students, advocating for a diverse curriculum in General Biology. His tenure was marked by collaborative research projects, including a significant study on Trillium with Japanese botanists, which not only advanced scientific understanding but also strengthened international scientific cooperation.

Channell received hisB.S. degree in botany in 1947 and his M.S. degree in 1949 at Mississippi State College (now Mississippi State University). During his time there, he was also an instructor in botany from 1949 to 1951. Channell was a graduate assistant in the Department of Botany at Duke University, where he ultimately received his Ph.D. in 1955. He spent the next two years at Harvard University as a botanist on the staff of the Gray Herbarium–Arnold Arboretum.

Channell joined Vanderbilt in 1957 as an Assistant Professor of Biology. In 1963, he became the chairman of the newly established Department of General Biology and co-directed the Summer Institute of Evolution of Vascular Plants with his good friend and botanist Dr. Elsie Quarterman –– Vanderbilt’s “first female academic department chair.” Some classes Channell taught often had evolution themes such as ecological genetics, seminars in plant evolution, experimental taxonomy, biosystematics, and plant diversity.

Channell joined Vanderbilt in 1957 as an Assistant Professor of Biology. In 1963, he became the chairman of the newly established Department of General Biology and co-directed the Summer Institute of Evolution of Vascular Plants with his good friend and botanist Dr. Elsie Quarterman –– Vanderbilt’s “first female academic department chair.” Some classes Channell taught often had evolution themes such as ecological genetics, seminars in plant evolution, experimental taxonomy, biosystematics, and plant diversity.

During Channell’s time at Vanderbilt, he was also the director of 3 projects: 1) Vanderbilt’s Institute in Plant Evolution for college teachers of botany which the National Science Foundation (NSF) funded, 2) Vanderbilt’s graduate training program in plant evolution which was provided under the National Defense Education Act, and 3) a research project in which Vanderbilt botanists and Japanese botanists at Kyushu University made comparative studies of the evolutionary and migrational history of Trillium.

However, Channell’s most significant grant that he received from the NSF was titled “Cytotaxonomic and Biochemical Studies of the Origin, Distribution and Relationships of Species of Trillium (Liliaceae).” Through the use of staining to determine the chromosomes of the eastern North American Trillium individuals within and across species, Channell aimed to better understand the natural taxonomic units comprising this genus. He had originally intended for this research to last 2 years (July 1, 1963-July 1, 1965), but he requested an extension of 3 more years to July 1, 1968.

The NSF explained their rationale behind funding Channell’s research in the following manner: “We feel that this project will not only permit important studies to be made which would not have been possible otherwise, but will also contribute substantially to the strengthening of cooperative endeavors in science between the United States and Japan.”

The NSF explained their rationale behind funding Channell’s research in the following manner: “We feel that this project will not only permit important studies to be made which would not have been possible otherwise, but will also contribute substantially to the strengthening of cooperative endeavors in science between the United States and Japan.”

Due to pre-existing Japanese Trillium research that Channell relied on and referenced, there were political undertones to his work. In several of Channell’s proposals for extensions to the NSF, he often cited the U.S.-Japan Cooperation Program as the main reason why he should continue his research on Trillium. When Channell discovered that Mr. Yoshimichi Kozuka––a Japanese research associate in his lab with extensive knowledge of Trillium research––would have to leave the U.S. soon due to his visa expiration, Channell advocated for Kozuka’s stay and salary support. Similarly, Channell filed considerable paperwork to hire Mr. Masaaki Ihara from the National Institute of Genetics in Mishima, Japan as a research associate to gain his expertise in this subject matter.

In September 1973, Channell co-published a paper “Distribution and Evolutionary Significance of Chromosome Variation in Trillium ovatum” with Dr. Ichiro Fukuda of Tokyo Woman’s Christian College -- the first paper published in the journal Evolution from Vanderbilt University. The paper discussed the primary distributions of this genus in the Pacific coast region of western North America and the Rocky Mountain region as well as analyzed the chromosomal variation among Trillium species.

Channell’s collaborations with hisJapanese colleagues to further his research eventually were proven successful and effective; in 1996, Trillium channellii (Trilliaceae)––a new tetraploid species from eastern Hokkaido (northern Japan)––was chosen to honor Channell.

As Novon––a journal for botanical nomenclature––highlighted, Channell’s “interest in Trillium and support of research on taxonomy, cytogenetics, chemistry, and ecology of this genus during the early 1960s account (directly or indirectly) for much new information published about these plants since that time by us as well as many others. He challenged and encouraged those with whom he worked, often without receiving due credit for original ideas.”

Channell’s selflessness and altruism permeated beyond his lab and to the greater Vanderbilt community. Because Channell also served on the Vanderbilt Planning Study’s Committee on Graduate and Postgraduate Studies, he applied for grants intended to improve undergraduate and graduate equipment for courses in General Biology. Channell argued that more consistent education on topics such as Embryology, Parasitology, Plant Physiology, and Cytology would provide an avenue for undergraduates to further explore these subjects in the research setting if they wished to pursue graduate studies. He also led many plant identification field trips and workshops at the Cheekwood Botanical Garden.

Channell’s selflessness and altruism permeated beyond his lab and to the greater Vanderbilt community. Because Channell also served on the Vanderbilt Planning Study’s Committee on Graduate and Postgraduate Studies, he applied for grants intended to improve undergraduate and graduate equipment for courses in General Biology. Channell argued that more consistent education on topics such as Embryology, Parasitology, Plant Physiology, and Cytology would provide an avenue for undergraduates to further explore these subjects in the research setting if they wished to pursue graduate studies. He also led many plant identification field trips and workshops at the Cheekwood Botanical Garden.

In a progress report to the NSF, Channell confidently stated that “the undergraduate program in biology at Vanderbilt has been markedly improved through the use of equipment purchased under this grant, and that, in general, the grant has had the intended results.”

In July 1973, Channell co-authored the paper “Fragrance Analyses of Trillium luteum and Trillium cuneatum (Liliaceae)” with his student James T. Murrell in the Journal of the Tennessee Academy of Science. The paper determined 12 different compounds responsible for the fragrances of the titular species using gas chromatography, a lab technique that separates different components of a mixture. The only compound whose identity was determined was terpene alcohol linalool, the major fragrance component of T. luteum responsible for its lemon-like odor. After receiving his Ph.D. at Vanderbilt, Murrell became a professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at Mississippi University for Women, and he continued researching various floral fragrances.

In 1977, Channell’s study titled “Perilla Ketone: A Potent Lung Toxin from the Mint Plant, Perilla frutescens Britton” was published in the journal Science. The researchers first synthesized the compound perilla ketone, an essential oil of the Asia-imported and “garden escapee.” Perilla frutescens––more commonly known in the U.S. as “purple mint plant,” “beefsteak plant,” “perilla mint,” and “perilla.” Then, after determining the specific toxic reactions and minimal lethal dose value of perilla ketone in lab mice, the researchers concluded that perilla ketone demonstrated lung toxicity for lab animals. Therefore, the researchers used this finding to explain the outbreaks of pulmonary emphysema among cattle and livestock that grazed the plant. The paper also analyzed the potential toxic hazards of Perilla frutescens when consumed and the health risks associated with humans eating primarily Asian cuisine or medicine containing perilla.

Another student Channell supervised was Robert L. Beckmann, Jr., who researched the genus Hydrophyllum L. (Hydrophyllaceae). Beckmann’s study published in American Journal of Botany called “Biosystematics of the Genus Hydrophyllum L. (Hydrophyllaceae)” analyzed the interrelationships of various Hydrophyllum species, a group of mesophytic herbs capable of growing in moderate temperatures and levels of moisture on the east and west coasts of North America. Beckmann continued research at North Carolina State University.

Channell also conducted research on the Buxaceae or the Boxwood family, which consists of monoecious evergreen shrubs, subshrubs, and rhizomatous herbs. In one section of his paper “The Buxaceae in the Southeastern United States” which was published in Journal of Arnold Arboretum, Channell suggested the possibility of phylogenic relationships among the Buxaceae, the Stylocerataceae, and the Didymeleaceae due to their close geographic presence to one another on the major continental land masses of the world. This study also analyzed the chemical components of a liquid wax derived from the seeds of Simmondsia chinesis, a long-lived, low shrub indigenous to the Sonoran Desert of California, Arizona, and northern Mexico. Because this wax is used in many cosmetics or substituted for other waxes such as beewax or spermaceti (sperm-whale oil), Channell concluded his paper by emphasizing the strong economic interest of Simmondsia. After the publication of this paper in 1987, one of Channell’s students Herbert C. Robbins studied the genus Pachysandra. After completing his studies at Vanderbilt, Robbins went on to teach at Belmont College (now Belmont University) and Baylor University. Robbins eventually became an Assistant Professor and Chairman of the Department of Biology at Kentucky Southern College.

Channell spent his time at Vanderbilt contributing to research and academia that was greater than himself. Even after his death on August 10, 2001, Channell left behind a legacy scholarship to students studying the sciences at his alma mater Copiah-Lincoln Community College.

By Sheila Chau, Library Buchanan Fellow

Dr. Mary Voigt was a professor in Vanderbilt’s Anthropology department from 1971 to 1978. She was also a lecturer at University of Pennsylvania, Bryn Marw College, and College of William and Mary. She holds degrees from Marquette University (B.A. in History and English) and the University of Pennsylvania (Ph.D. in Anthropology).

Dr. Mary Voigt was a professor in Vanderbilt’s Anthropology department from 1971 to 1978. She was also a lecturer at University of Pennsylvania, Bryn Marw College, and College of William and Mary. She holds degrees from Marquette University (B.A. in History and English) and the University of Pennsylvania (Ph.D. in Anthropology).

At Vanderbilt, specifically, one of the main classes she taught was human evolution. Other interesting courses she taught at different institutions include human origins, the cells in archaeology and history, and seminars on problems in anthropological theory.

One of Voigt’s accomplishments was finding the Neolithic vino, the oldest bottle of wine on record. Voigt has done some archaeological work in Iran, and during exactions at Haji Firuz Tepe (northern Zagros Mountains near the city of Urmia, six wine bottles were discovered in what was thought to be the kitchen of a neolithic home. The wine bottles that were found were found to be roughly 7,000 to 7,400 years old. Voigt analyzed a yellowish residue on the pottery, and she found that the material had calcium tartrate and terebinth, a resin, from a tree.

Tartaric acid is often found in grapes. Voigt and her team found that the tartaric acid was converted into the calcium salt by interacting with soil. The finding of ancient retsina made the origins of wine 2,000 years earlier.

Voigt was passionate about archaeology, and she thought archaeology as pertinent to unearthing stories from the past. Each artifact that is found is not an isolated instrument. Rather, she thought of each artifact as something that was a part of a larger story.

Photo credit wm.edu news release

By: Neomi Chen, Evolutionary Studies undergraduate communications assistant

Early Life & Education

Born on June 19, 1957, Dr. Nils Olof “Olle” Pellmyr spent much of his childhood exploring and studying the insects and bugs around him in Stockholm, Sweden. In high school, he was a finalist in the 27th International Science and Engineering Fair and traveled to Denver, Colorado to present his project on the largely-unstudied measuring worms of the Nordic countries. As highlighted in his obituary, this was Pellmyr’s first encounter with the United States, where he eventually settled. After Pellmyr earned his Ph.D. in 1985 at Uppsala University in Sweden, he began his postdoctoral fellowship with Dr. John Thompson at Washington State University where he studied Greya moths. From 1994 to 2002, Pellmyr was a researcher and full-time evolutionary biology professor in the Department of Biology at Vanderbilt University while his wife completed her medical residency at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. During his time at Vanderbilt, Pellmyr served as the Director of Graduate Studies and taught various “Special Topics” courses within the department. In the fall semester of 1998, Pellmyr taught a class titled “Plant-Animal Interactions” that focused on the ecology and evolution of various species, communities, and individuals. With two half-day Saturday field trips offered, Pellmyr ensured his students would have plenty of hands-on experience. In 2002, Pellmyr obtained a faculty position in the biology department at the University of Idaho and moved to Moscow, Idaho with his family to continue teaching and researching the interactions between yuccas and yucca moths.

Born on June 19, 1957, Dr. Nils Olof “Olle” Pellmyr spent much of his childhood exploring and studying the insects and bugs around him in Stockholm, Sweden. In high school, he was a finalist in the 27th International Science and Engineering Fair and traveled to Denver, Colorado to present his project on the largely-unstudied measuring worms of the Nordic countries. As highlighted in his obituary, this was Pellmyr’s first encounter with the United States, where he eventually settled. After Pellmyr earned his Ph.D. in 1985 at Uppsala University in Sweden, he began his postdoctoral fellowship with Dr. John Thompson at Washington State University where he studied Greya moths. From 1994 to 2002, Pellmyr was a researcher and full-time evolutionary biology professor in the Department of Biology at Vanderbilt University while his wife completed her medical residency at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. During his time at Vanderbilt, Pellmyr served as the Director of Graduate Studies and taught various “Special Topics” courses within the department. In the fall semester of 1998, Pellmyr taught a class titled “Plant-Animal Interactions” that focused on the ecology and evolution of various species, communities, and individuals. With two half-day Saturday field trips offered, Pellmyr ensured his students would have plenty of hands-on experience. In 2002, Pellmyr obtained a faculty position in the biology department at the University of Idaho and moved to Moscow, Idaho with his family to continue teaching and researching the interactions between yuccas and yucca moths.

Yucca and Yucca Moths Research

The Selective-Abortion Hypothesis

In 1994, Pellmyr co-authored the paper “Evolutionary Stability of Mutualism between Yuccas and Yucca Moths” in Nature with his graduate student Dr. Chad J. Huth. They first described the mutualistic relationship between yuccas and yucca moths: yucca flowers attract female moths that lay eggs in the flowers, the moths then deliberately pack pollen into place to fertilize the flowers, and the flowers produce fruit containing seeds for newly hatched moth larvae to eat. The paper then presents the first evidence that a cryptic mechanism exists in the yucca/yucca moth relationship to stabilize these interactions. The mechanism that they suggested was the selective abortion of flowers with heavy egg loads to promote evolutionary stability. By using Yucca filamentosa (Agavaceae) and its exclusive moth pollinator, Tegeticula yuccasella (Lepidoptera: Prodoxidae), Pellmyr and Huth tested for the presence of moth-induced selective abortion and observed that Y. filamentosa aborted flowers that held large numbers of larvae to prevent larval damage to their flowers and excessive exploitation from the moths.

In 1994, Pellmyr co-authored the paper “Evolutionary Stability of Mutualism between Yuccas and Yucca Moths” in Nature with his graduate student Dr. Chad J. Huth. They first described the mutualistic relationship between yuccas and yucca moths: yucca flowers attract female moths that lay eggs in the flowers, the moths then deliberately pack pollen into place to fertilize the flowers, and the flowers produce fruit containing seeds for newly hatched moth larvae to eat. The paper then presents the first evidence that a cryptic mechanism exists in the yucca/yucca moth relationship to stabilize these interactions. The mechanism that they suggested was the selective abortion of flowers with heavy egg loads to promote evolutionary stability. By using Yucca filamentosa (Agavaceae) and its exclusive moth pollinator, Tegeticula yuccasella (Lepidoptera: Prodoxidae), Pellmyr and Huth tested for the presence of moth-induced selective abortion and observed that Y. filamentosa aborted flowers that held large numbers of larvae to prevent larval damage to their flowers and excessive exploitation from the moths.

After the Nature publication, Pellmyr’s written documents to the National Science Foundation (NSF) about the project titled “Coevolution and Selective Abscission/Abortion in the Yucca-Yucca Moth Interaction” revealed their plans for future research spanning from 1995 to 1999. They wanted to determine whether the selective abortion mechanism evolved through novel traits or the result of preadaptations in the interacting organisms. In a budget justification document to the NSF, Pellmyr indicated that he would lead the work in Tennessee while Huth would have full responsibility for the pollination-effect experiment at Spring Grove in Cincinnati given his three years of experience with this system. On April 1, 2000, Huth and Pellmyr’s research on this new dimension of yucca/yucca moth interaction was published in the journal Ecology. Their paper “Pollen-Mediated Selective Abortion in Yuccas and Its Consequences for the Plant-Pollinator Mutualism” detailed how they created pollination experiments in two Y. filamentosa populations and found that a pollen load larger than that typically provided by T. yuccasella moths increased fruit retention of the flowers. Through this study, Pellmyr and Huth were able to define more specifically the correlation between pollen loads and selective abortion of moth eggs.

After the Nature publication, Pellmyr’s written documents to the National Science Foundation (NSF) about the project titled “Coevolution and Selective Abscission/Abortion in the Yucca-Yucca Moth Interaction” revealed their plans for future research spanning from 1995 to 1999. They wanted to determine whether the selective abortion mechanism evolved through novel traits or the result of preadaptations in the interacting organisms. In a budget justification document to the NSF, Pellmyr indicated that he would lead the work in Tennessee while Huth would have full responsibility for the pollination-effect experiment at Spring Grove in Cincinnati given his three years of experience with this system. On April 1, 2000, Huth and Pellmyr’s research on this new dimension of yucca/yucca moth interaction was published in the journal Ecology. Their paper “Pollen-Mediated Selective Abortion in Yuccas and Its Consequences for the Plant-Pollinator Mutualism” detailed how they created pollination experiments in two Y. filamentosa populations and found that a pollen load larger than that typically provided by T. yuccasella moths increased fruit retention of the flowers. Through this study, Pellmyr and Huth were able to define more specifically the correlation between pollen loads and selective abortion of moth eggs.

Cheater Moth Species

As Pellmyr and Huth collaborated on the NSF project, they discovered two species of cheater yucca moths. Cheater moths, they explained, were non-pollinating species, but they still maintained the habit of seed consumption. Because T. intermedia and T. corruptrix––the two cheater species that Pellmyr and Huth found––didn’t pollinate the yucca flowers, they disrupted the mutualistic interaction. These non-pollinating moths decreased plant benefit by dramatically increasing the proportion of destroyed yucca seeds. By depositing their eggs when the fruits were full-sized, the larvae of both cheater species fed on seeds together with coexisting pollinator larvae. With this finding, Pellmyr and Huth expanded their project to include the phylogenetic origins of cheating and the dynamics of pollinator-cheater-plant interactions.

As Pellmyr and Huth collaborated on the NSF project, they discovered two species of cheater yucca moths. Cheater moths, they explained, were non-pollinating species, but they still maintained the habit of seed consumption. Because T. intermedia and T. corruptrix––the two cheater species that Pellmyr and Huth found––didn’t pollinate the yucca flowers, they disrupted the mutualistic interaction. These non-pollinating moths decreased plant benefit by dramatically increasing the proportion of destroyed yucca seeds. By depositing their eggs when the fruits were full-sized, the larvae of both cheater species fed on seeds together with coexisting pollinator larvae. With this finding, Pellmyr and Huth expanded their project to include the phylogenetic origins of cheating and the dynamics of pollinator-cheater-plant interactions.

In July 2000, Pellmyr embarked on another NSF-funded project titled “Evolution of a Cheater Yucca Moth: An Experimental Approach” with his graduate student Dr. Kari Segraves, now a biology professor at Syracuse University. They aimed to use a recently evolved cheater yucca moth and its pollinating sister species in Florida and adjacent areas to test the first explicit scenario for any obligate mutualism of how it can evolve. Obligate mutualism describes a relationship between two completely co-dependent species such as the yucca moths and yucca plant. Pellmyr and Segraves experimentally tested the hypothesis that the pollinator that gave rise to the cheater moth had the behavioral plasticity and ovipositor morphology to make the shift from pollinator to cheater habit comparatively easily. This project was a part of Segraves’ dissertation research, and she sought to address the following questions: Is the pollinator T. cassandra preadapted for cheating? Has ecological overlap of the pollinators T. cassandra and T. yuccasella facilitated mutualism reversal? How do yuccas avoid excessive exploitation by a superficially-ovipositing moth? In 2002, Pellmyr’s 3 NSF grants were transferred to the University of Idaho to continue this research at his new institution.

Collaborative Research with Leebens-Mack Lab at Colgate University

In April 1999, Pellmyr submitted a proposal titled “Collaborative Research: Molecular Phylogenetics and Coevolution in Yuccas and Yucca Moths” to the NSF. In his proposal, Pellmyr stated, “Funds are requested to use multi-gene sequencing to complete robust organismal phylogenies for both yuccas (Agavaceae) and yucca moths (Prodoxidae: Lepidoptera). The phylogenies will then be used to test hypotheses of coevolution, cospeciation, and host shifts in diversification.”

His proposal was rejected despite Pellmyr’s asserting that this research would open a venue for analyzing how coevolutionary processes interact at the trait level to contribute to the generation of biodiversity. However, Pellmyr resubmitted the proposal on September 1, 2000, and successfully received funding.

His new project “Molecular Systematics and Coevolution in Yucca Moths” listed 3 goals: 1) use morphological and molecular tools to perform a systematic and phylogenetic revision of the yucca moths, 2) test hypotheses about the evolution of non-pollinating yucca moths and moth host specificity, and 3) test hypotheses about ecological tracking in life history diversification among “bogus” yucca moths. By collaborating with Dr. James H. Leebens-Mack’s lab at Colgate University to do most of the yucca work, Pellmyr hoped to make a first paradigm for studies of coevolving mutualisms with Leebens-Mack’s expertise. Prior to moving to Colgate, Leebens-Mack was a postdoctoral associate in Pellmyr’s Lab, working together on several studies that were published in journals such as Nature, Evolution, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, American Journal of Botany, and American Naturalist. Therefore, Pellmyr and Leebens-Mack were already familiar with collaborating with one another, and this phylogenetic study represented the second and final part of their project to establish a robust phylogenetic framework for yuccas and yucca moths. At the end of their collaborative research on this topic, Pellmyr and Leebens-Mack systematically revised the T. yuccasella complex and identified the phylogenetic origins of the 2 biologically distinct types of non-pollinating “cheater” yucca moths. Leebens-Mack is now a professor of plant biology within the Department of Plant Biology at the University of Georgia.

His new project “Molecular Systematics and Coevolution in Yucca Moths” listed 3 goals: 1) use morphological and molecular tools to perform a systematic and phylogenetic revision of the yucca moths, 2) test hypotheses about the evolution of non-pollinating yucca moths and moth host specificity, and 3) test hypotheses about ecological tracking in life history diversification among “bogus” yucca moths. By collaborating with Dr. James H. Leebens-Mack’s lab at Colgate University to do most of the yucca work, Pellmyr hoped to make a first paradigm for studies of coevolving mutualisms with Leebens-Mack’s expertise. Prior to moving to Colgate, Leebens-Mack was a postdoctoral associate in Pellmyr’s Lab, working together on several studies that were published in journals such as Nature, Evolution, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, American Journal of Botany, and American Naturalist. Therefore, Pellmyr and Leebens-Mack were already familiar with collaborating with one another, and this phylogenetic study represented the second and final part of their project to establish a robust phylogenetic framework for yuccas and yucca moths. At the end of their collaborative research on this topic, Pellmyr and Leebens-Mack systematically revised the T. yuccasella complex and identified the phylogenetic origins of the 2 biologically distinct types of non-pollinating “cheater” yucca moths. Leebens-Mack is now a professor of plant biology within the Department of Plant Biology at the University of Georgia.

Legacy

Pellmyr died on December 4, 2017, but he trained many students to follow in his footsteps as scientists. After Leebens-Mack left Pellmyr’s lab, Pellmyr began mentoring Dr. David Althoff, a postdoctoral associate. Althoff is now an Associate Professor and Associate Chair in the Biology Department at Syracuse University, and his research interests lie in the evolutionary ecology of species interactions, insect community ecology, molecular ecology, and phylogenetics.