The Changing Spaces of Dating Apps since COVID-19

By Abigail Trozenski, German, Russian & East European Studies & CMAP

With the annual celebration of Valentine’s Day recently passed, let us examine modern celebrations of romance forming in the world of online dating services. Turning to digital media for all things love has been on the rise since the early 2000s, and we’re living in a time of swipe left-swipe right-matching immediacy. Today, studies in all shapes and sizes explore the implications of dating apps.[1] In the last few months, I’ve been drawing from these studies and collecting interviews for my podcast, the Happs with the Apps, discussing all things dating apps. Not only have I learned much about how users navigate virtual spaces in search of friendship, love, and intimacy, but I’ve also found that online dating has made immense strides since the COVID pandemic.

Online dating services are systems that provide websites or software applications enabling people to introduce themselves to potential connections through the internet with the goal of developing friendly, romantic, or sexual relationships. These services allow users to become members through a profile by uploading information including age, gender, sexual orientation, location, often along with photos or videos. Members can view other members’ profiles and decide whether to initiate contact. If so, this contact takes place in an online space through chatting services where arrangements to meet in person may be possible.

Since the advent of Match.com (now Match) in 1993, online dating services expanded through the early 2000s allowing more accessibility after partnerships with internet service providers like AOL and MSN. In 2009, IAC (an American holding company owning 100+ brands mostly in media and the Internet) formed Match Group as a conglomerate of Match.com and other online dating sites, including Meetic (launched 2001), PlentyOfFish (2003), OkCupid (2004), Tinder (2012), Hinge (2012), Ship (2019) and more, totaling to over 45 global dating companies and becoming a separate, global company in 2020.

In competition with Match Group are apps like Badoo and Bumble. Founded in 2006 by Russian entrepreneur Andrey Andreev, Badoo rivals Tinder as the largest worldwide platform with Bumble rising in the ranks. Tinder co-founder Whitney Wolfe Heard launched Bumble in 2014 shortly after leaving Tinder.

Revenue from online dating in the United States stood at 602 million U.S. dollars in 2020.[2] Some sites, like Match and eHarmony, rely solely on paid membership subscriptions. Many sites are completely free to users, relying on advertising for revenue, while others, like Badoo, Tinder, Hinge, Bumble and more, use a freemium revenue model. The latter offer registration and a basic product free of charge with the option of additional features or services at a cost. While paying for additional features often allows users to filter matches through profile controls, some online dating services target specific demographics based on various features like religion, sexual orientation, location, shared interests, or most recently- vaccination status.

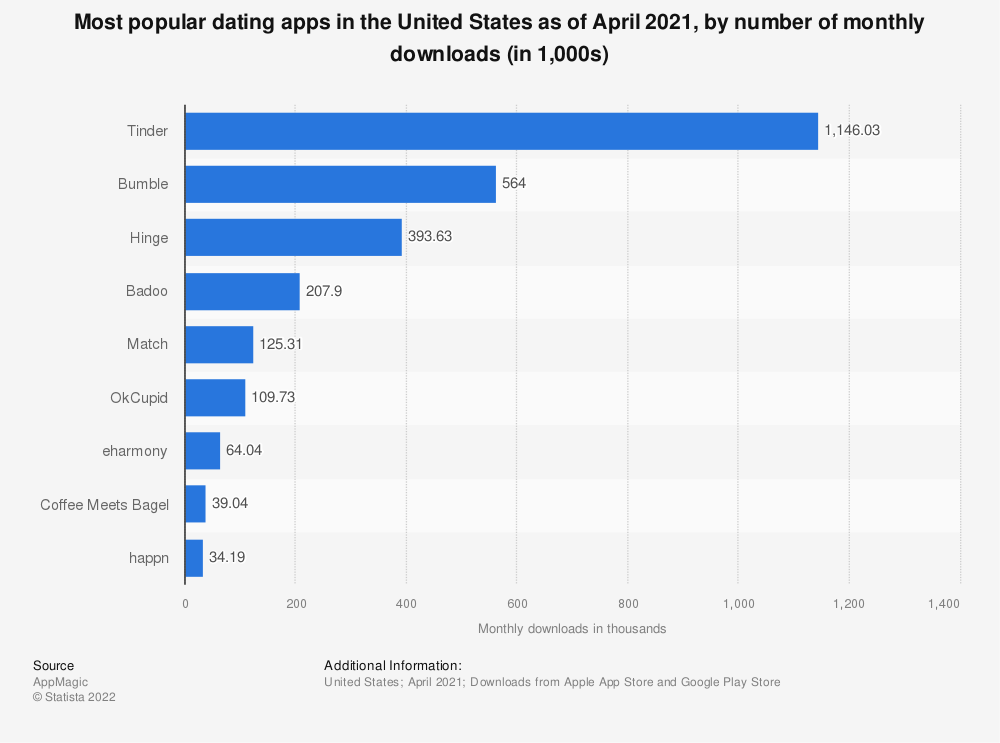

In 2021, Tinder ranked first by downloads in the United States generating 15 million users, followed by Bumble with 8.5 million downloads, and Plenty of Fish with 7.4 million downloads. As evident in the graph below, the aforementioned apps saw a significant rise in downloads and membership.

A 2020 systematic review on dating app studies from 2016-2020 concludes with the following statement:

Dating apps have come to stay and constitute an unstoppable social phenomenon, as evidenced by the usage and published literature on the subject over the past five years. These apps have become a new way to meet and interact with potential partners, changing the rules of the game and romantic and sexual relationships for millions of people all over the world. Thus, it is important to understand them and integrate them into the relational and sexual life of users… Finally and unavoidably, knowledge about the phenomenon of dating apps collected in this systematic review can have positive implications for users, who may have at their disposal the necessary tools to make a healthy and responsible use of these applications, maximizing their advantages and reducing the risks posed by this new form of communication present in the daily life of so many people.[3]

Not long after Castro and Barrada published their research, “Dating Apps and Their Sociodemographic and Psychosocial Correlates: A Systematic Review,” the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic struck. Online dating services were put to the test to make healthy and responsible decisions for their users and work alongside the preventive measures like social distancing, quarantining, and masking implemented at the onset of the coronavirus pandemic.

An April 2020 survey of Millennial dating app users in the United States revealed that 31% of respondents were using online dating services more than prior to the pandemic.[4]

With an increase in number of users and the amount of time people spent on dating apps, one may wonder: how did dating apps take the responsibility to refine their platforms as safe spaces for users to communicate and form relationships during a global pandemic?

Tinder cited 2020 as the app’s busiest year in their publication, The Future of Dating is Fluid. In November 2020, Bumble posted a video of epidemiologist and infectious disease specialist, Dr. Ravina Kullar, discussing COVID safety when dating. Similarly, in October 2021, Hinge worked with the U.S. Surgeon General, Dr. Vivek Murthy to offer a video of dating tips for the fall.

For times of quarantining and social distancing, apps encouraged users to stop meeting in person and stick to online engagement. This led to apps hosting online events, emphasizing online activities geared towards physical distancing. Services like virtual speed dating, dating advice sessions, virtual therapy, and concerts emerged, and new tools were introduced allowing users to add videos to their profile as well as allow for users to video chat upon matching.

With in-person meetings regaining popularity since the introduction of COVID-19 vaccines, apps like Tinder, Hinge, OkCupid, and Bumble partnered with the government to add a badge to profiles indicating that users have been vaccinated. Tinder also gave away at-home COVID test kits in March 2021.

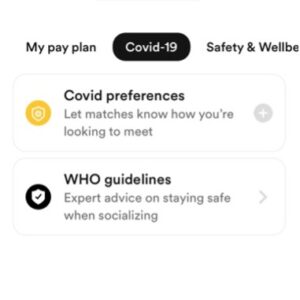

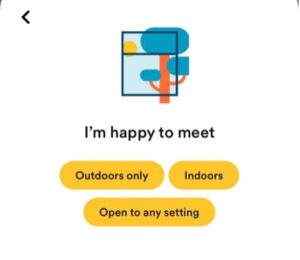

After exploring some of the highest-ranking dating apps, we found that Bumble’s features were the most in-depth by offering users ways of letting matches know their preferences. Included at the basic level of the profile is a COVID-19 tab, where users have access to WHO guidelines along with COVID-19 choices, asking the following questions to gauge comfortability with meeting other users during the pandemic:

Overall, the wide range of online dating services has taken on the pandemic with clever adaptions and digital trends perhaps forever integrated into the landscape of apps. Have you used any of the dating apps listed above in the last couple of years? Have you had any dating experiences particularly unique due to the pandemic? If you are interested in sharing and discussing some, any, or all these topics on the Happs with the Apps podcast, please don’t hesitate to reach out. Contact me at “a.trozenski [at] vanderbilt [dot] edu,” and we can coordinate a recording session. *Discretion is a priority, so upon request, your interview may be completely anonymous*

Alternative Apps NOT Owned by Match Group

If you are interested in perusing the world of online dating services and the names previously listed are too outdated, some *niche* dating services include:

Affectionately known as “the cat person’s dating app,” users who fancy themselves cat-lovers mingle with cat-owners to find their purrrfect match. Based around cats, the website is “the best way for cat-lovers and cat owners to find a purrfect match, plan a cat-focused date, and learn about new cat products and treats! Tabby is for people with cats and people who want to get cats in the future.”

Are you a dog owner feeling excluded? No worries, there is a dating app for dog people too. Much like Tabby, Dig is geared towards dog people interested in meeting other dog-lovers. Woof! Both Tabby and Dig launched in 2018 and beyond connecting pet lovers looking for love, ad materials promote adoption and share educational material about animals.

With the slogan, “city folks just don’t get it,” Farmers Only prides itself on offering a dating service not just for farmers, but for anyone interested in living a more rural lifestyle.

Think farmers only, but for those who love the ocean.

Notes

[1] See bibliography for links to recent studies/dating app literature.

[2] Statista Digital Market Outlook. (March 30, 2021). Online dating revenue in the United States from 2017 to 2024 (in million U.S. dollars) [Graph]. In Statista. Retrieved February 24, 2022, from https://www-statista-com.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/statistics/426025/revenues-us-online-dating-companies/

[3] Ángel Castro and Juan Ramón Barrada. “Dating Apps and Their Sociodemographic and Psychosocial Correlates: A Systematic Review.”

[4] Morning Consult. “Share of Millennial dating app users in the United States who are using online dating apps or services now more or less amid the coronavirus pandemic as of April 2020 .” Chart. April 27, 2020. Statista. https://www-statista-com.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/statistics/1114398/millennial-online-dating-usage-during-covid-pandemic/

Sources

Albury, Kath, Jean Burgess, Ben Light, Kane Race, and Rowan Wilken. “Data Cultures of Mobile Dating and Hook-up Apps: Emerging Issues for Critical Social Science Research.” Big Data & Society, (December 2017). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951717720950.

Albury, Kath, and Paul Byron. “Safe on My Phone? Same-Sex Attracted Young People’s Negotiations of Intimacy, Visibility, and Risk on Digital Hook-Up Apps.” Social Media + Society, (October 2016). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116672887.

“Leading dating apps in the United States in 2021, by downloads (in millions).” Chart. December 27, 2021. Statista. https://www-statista-com.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/statistics/1284747/us-top-dating-apps-by-downloads/

Castro, Ángel, and Juan Ramón Barrada. “Dating Apps and Their Sociodemographic and Psychosocial Correlates: A Systematic Review.” International journal of environmental research and public health, vol. 17, no. 18 (2020): 6500. doi:10.3390/ijerph17186500

Curry, David. “Bumble Revenue and Usage Statistics (2022).” Business of Apps. January 11, 2022. https://www.businessofapps.com/data/bumble-statistics/

Curry, David. “Dating App Revenue and Statistics (2022).” Business of Apps. February 23, 2022. https://www.businessofapps.com/data/dating-app-market/

David, Gaby, and Carolina Cambre. “Screened Intimacies: Tinder and the Swipe Logic.” Social Media + Society, (April 2016). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116641976.

Gibbs, Jennifer L., Nicole B. Ellison, and Rebecca D. Heino. “Self-Presentation in Online Personals: The Role of Anticipated Future Interaction, Self-Disclosure, and Perceived Success in Internet Dating.” Communication Research 33, no. 2 (April 2006): 152–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650205285368.

Hjorth, Larissa. “Mobile Intimacy in an Age of Affective Mobile Media.” Feminist Media Studies. 12, no. 2 (2012): 477–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2012.741860.

“Online Dating in the United States” (Statista, 2021)

Ranzini, Giulia, and Christoph Lutz. “Love at First Swipe? Explaining Tinder Self-Presentation and Motives.” Mobile Media & Communication 5, no. 1 (January 2017): 80–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050157916664559.

“Share of Millennial dating app users in the United States who are using online dating apps or services now more or less amid the coronavirus pandemic as of April 2020 .” Chart. April 27, 2020. Statista. https://www-statista-com.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/statistics/1114398/millennial-online-dating-usage-during-covid-pandemic/.

Tran, Alvin, Suharlim, Christian, Mattie, Heather et al. “Dating app use and unhealthy weight control behaviors among a sample of U.S. adults: a cross-sectional study.” Journal of Eat Disorders vol. 7, no. 16 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-019-0244-4