The Belletristic Roots of Digital Humanities: A Retrospective Look at “The Long Way Round” (January 2020 DH Guest Lecture)

On January 16th, 2020, The Center for Digital Humanities at Vanderbilt University welcomed Professors and Digital Humanists Brian Pytlik Zillig and Stephen Ramsay of the University of Nebraska. In their public lecture “The Long Way Around: Digital Modalities and Creative Convergence,” Zillig and Ramsay sought to spark a reimagined Digital Humanities (DH), to shift the commonly-held believe that the young practice seeks to “scientize” humanistic endeavor. Instead, the pair aspires to reorient DH towards its belletristic roots, sharing various collaborative media projects that stemmed from their engagement with computational text analysis.

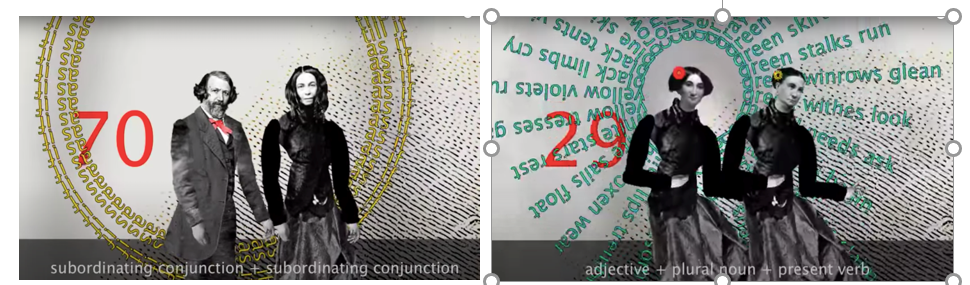

Experimenting with different modes of text analysis, Zillig developed two XML-based frameworks. The first, TokenX, allow users to manipulate and visualize words, sequences of words, and expressions. On the other hand, Indigo, a Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) XML-based application, allows one to import and transform archival photographs as well as linguistic elements. The application can also read XML-notated musical compositions. One such project, Perfect Motion, created by Zillig in collaboration with Brett Barney, features animated archival images of Walt

Whitman, Alfred Tennyson, Robert and Elizabeth Browning, Henry Longfellow, and Alice and Phoebe Cary. The dancing figures of these great English and American poets are accompanied by music and a textual analysis of their works, broken down into categories such as uses of color, phrasing patterns, and evolution of grammar in age.

A frequent collaborator of Zillig, including the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation funded Abbot Project, Ramsay’s interest in computational text analysis and visualization began 20 years ago with a mapping project based on Shakespeare’s plays. In tracking characters’ paths, Ramsay examined the visual structure of Shakespearian comedies and tragedies, and identified centralized spaces. Ultimately, Ramsay asserts that this type of text visualization can introduce humanists to new ways of seeing and, by consequence, produce new questions of humanistic inquiry. In measuring various components of literary works, the practitioner touts his collaborative projects with Zillig as “provocations born from systems of constraint.”

Despite the generative nature of their XML-based media projects that reach across disciplinary divides, Ramsay recognizes the push back against DH. Citing Matthew Kirschenbaum’s “What Is ‘Digital Humanities,’ and Why Are They Saying Such Terrible Things about It?” he concludes that the broad range of criticism is based on a vague construct of a discipline which is thought to have “physics envy.” Instead, Ramsay and Zillig celebrate and promote the tension between the belletristic and the scientific that DH scholarship cultivates. Their multi-media projects that use XML-based applications are but one example of the fertility of DH applications. At the end of their talk, both scholars emphasized the necessity of institutional recognition of DH labor, scientific and/or belletristic, looking towards studio art models for innovative ways to reconstruct tenure and promotion files in the Humanities.

Projecting an image of Jackson Pollock on all fours, paintbrush in hand, Ramsay recalled a Q&A session after one of his media-based DH presentations. A suspicious eye and a fast hand blurted out, “is this just art?” He retorted, “and what would be so bad about that?”

— Post by Meghan K. McGinley, 2019–2020 HASTAC Scholar