Digital Humanities and Pre-Modern Studies: A Review

By Samantha Rogers, Department of History and Mellon Graduate Student Fellow

Digital humanities are a dynamic and evolving field that, in my mind, serves two crucial functions. First, they offer methods of data gathering, analysis, and visualization that enable scholars to engage with new research questions and present their work in new ways. Second, they serve as a nexus between the academy and the public, and greatly increase the accessibility of information, documents, and pedagogical tools to a wider audience.

My research on early modern England has exposed me to many wonderful digital projects, a number of which have become invaluable in my own scholarship. However, I am disheartened by the fact that, for the most part, my discoveries have been entirely fortuitous. As a diverse and ever-expanding field, digital pre-modern studies have not yet developed a method of cataloguing and promoting the new and exciting projects being developed by various scholars. It is the intention of this post, therefore, to draw attention to the range of digital projects that focus on the pre-modern period as I highlight several examples that I have found particularly useful in my research or have otherwise stood out to me.

Digital Scholarly Editions

The digital scholarly edition is by far the most common and easily accessible digital humanities tool. It can take on any number of forms, which can be as simple as a hypertext edition of a single manuscript or printed work, and as complex as the collation and comparison of a text in many manuscripts (e.g., Canterbury Tales Project). Because the majority of medieval and early modern texts are not under copyright, these digital editions are often open access, and therefore serve an important role in bringing texts, documents, and information stuck behind a paywall or stored in archives to a broader audience. Moreover, digital scholarly editions present text transcribed from manuscripts and early printed sources (which are not generally OCR friendly) in a format that can be used for textual analysis. Though still improving, OCR technologies have not yet reached the ability to read most medieval manuscripts. Therefore, these scholarly editions, made possible by projects such as the Text Creation Partnership (TCP) and many thousands of hours of human labor, are essential in enabling textual and data analysis on medieval and early modern sources.

There is no end to the number of digital editions I have come across in my research. The English Broadside Ballad Archive (EBBA), for instance, offers nearly 10,000 early modern broadside ballads to the public for free, and the Early Stuart Libels project presents a text-based edition of early seventeenth-century political poetry from manuscript sources, and brings over 350 poems that have never before been published into the public domain. These are just two of the countless digital editions, many of which have been catalogued by the European Association for Digital Humanities. In what follows, I go into more detail on a few of these projects.

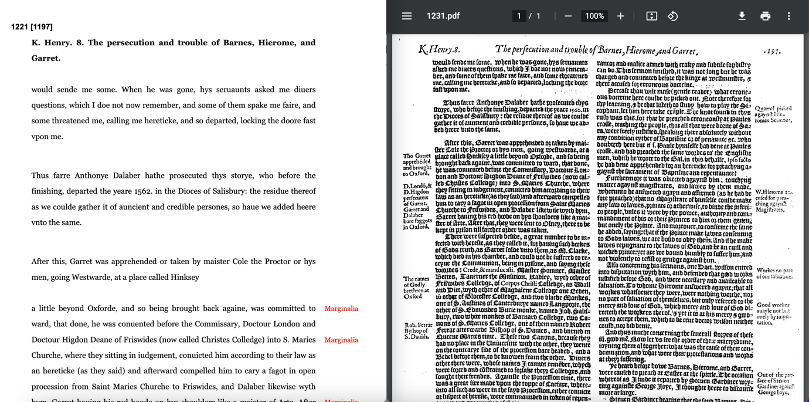

John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments Online is a digital edition that offers the transcribed text and high-quality facsimiles of woodcut illustrations from the most important martyrological text of sixteenth-century England. Not only does the project provide the text from each of the four editions in a way that allows for easy comparison, but it also offers tools to explore the textual transpositions and variations between editions. It has an extensive critical apparatus that presents commentary on the text and woodcuts, glossaries of people and places, original essays by several prominent scholars, and even a reference guide to the nineteenth-century edition of the Acts and Monuments that had hitherto stood as the definitive and much-cited edition.

The Internet Shakespeare is an ambitious digital project that bills itself as a “one-stop shop of resources in Shakespeare study.” It includes a digital edition of the works of William Shakespeare, a wealth of peer-reviewed secondary literature, and a digital archive that brings the Bard’s words to life. The digital edition of Shakespeare’s plays and poems includes the full text of each of his plays in modern and “old-spelling” transcriptions, information about the performance history, and high-quality facsimiles of early printed editions. The website provides extensive information about Shakespeare’s life and times—including biographies, maps, contemporary music, and information about the society, history, and politics of Elizabethan England. Finally, it brings the historical Shakespeare to the modern day by featuring a database of over 1000 stage and film productions (from the eighteenth century to today) and a gallery of artefacts from those productions, including playbills, scripts, photographs, and costume design. While the original intent of the website was to provide source material and related content to scholars, the secondary material and analysis are written in a way that makes it accessible to a broader audience, including students, actors, and directors.

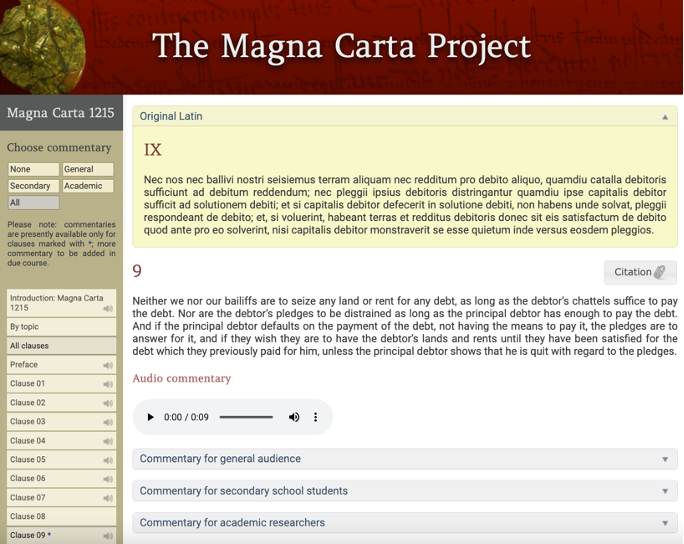

A final example that I want to draw attention to is the Magna Carta Project, which does an excellent job of presenting a project that is at once geared towards scholars, teachers, and the general public. The transcribed text of the Magna Carta (which can be viewed in the original Latin as well as a modern English translation) is presented alongside a variety of commentaries that offer different levels of analysis—one for the general public, one for use in the classroom, and one for academics. It provides high-quality facsimiles of manuscripts of the Magna Carta, as well as related primary sources, such as the diary and itinerary of King John, which allows for a day-by-day account of the making of the Magna Carta. Notably, it includes learning packs for teachers specifically geared towards the National Curriculum in England.

Historical GIS and Spatial Humanities

Mapping tools such as GIS have facilitated a spatial turn in the humanities. Modern, urban, and environmental historians quickly saw the potential of these tools, but it has taken a little longer for them to find a place in pre-modern studies. The development of historical GIS, which allows for the overlay of historical maps onto modern maps, and georeferencing historical sites onto present-day ones, has allowed pre-modern scholars to incorporate spatial data into their own research.

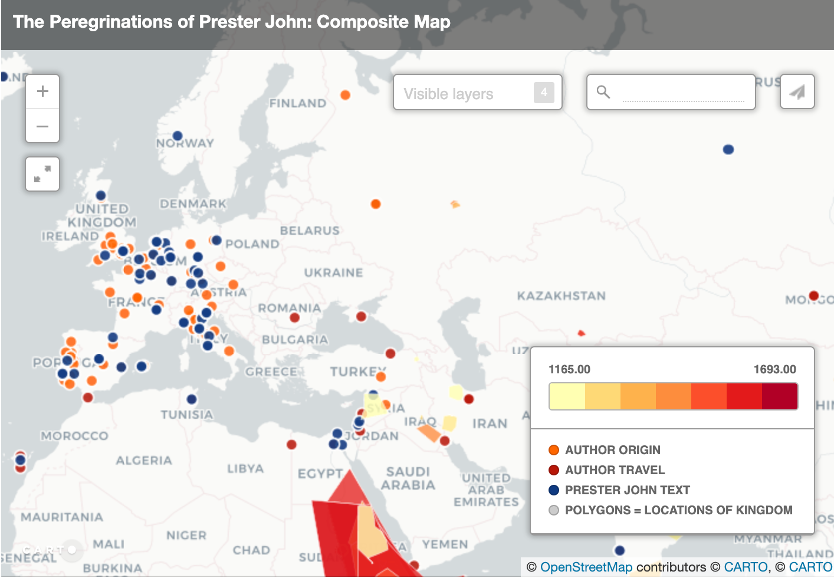

The International Prester John Project (part of the Global Middle Ages initiative) explores the way in which the legend of Prester John developed temporally and geographically over the course of six centuries (1150-1700). Prester John was a fabled Christian patriarch and king who was said to rule over a Christian nation lost among the Muslim and pagan kingdoms in the East. Over the centuries, his kingdom began to appear on maps, in travel narratives, and romance tales.

By bringing together historical texts and maps, the project traces the story of Prester John through the centuries and across the globe. The website contains a handful of dynamic maps rendered through GIS that chart the shifting locations of his kingdom and plot locations and arrivals of key texts in order to make a broader case about the significance of the Prester John legend in the European exploration of the peripheries of their known world.

Hidden Florence is a unique example of using GIS in combination with augmented reality to bring history to life. It launched as a smartphone app that allows you to experience Renaissance Florence through the eyes of five period characters who act as your guides as you walk through the city. It cleverly overlays a sixteenth-century map of Florence onto a modern map, so that visitors can go on a self-guided tour through the city while learning about Florence’s social and architectural history. This is an excellent example of the digital humanities being used in a public-facing way to bring the pre-modern period to life for a general audience.

The Virtual Paul’s Cross Project seeks to recreate the experience of worship and preaching at the churchyard of St. Paul’s Cathedral in early seventeenth-century London. It presents a visual 3D model of the Cathedral and churchyard, while simultaneously offering a spatial acoustic model that seeks to replicate the soundscape and acoustics to simulate the experience of listening to John Donne’s Gunpowder Day sermon in 1622.

Network Analysis

Several projects have drawn on network analysis to reconstruct social networks of the Renaissance and the early modern period. Drawing on primary and secondary sources such as correspondence and biographies, they illuminate relationships, networks, and communities and present the information in visual and dynamic ways that facilitate the development of new research questions.

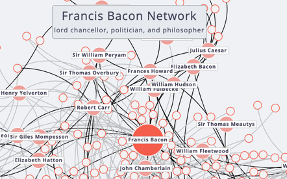

The most notable example of early modern network analysis is the Six Degrees of Francis Bacon project, which recreates social networks in early modern England. At the time of its launch, it had identified more than 13,000 individuals and 200,000 relationships, from diplomats and nobles to artists and playwrights. The wealth of structured information sheds light on networks, factions, and interest groups that shaped history. The format makes it a great example of how technology can be used to answer existing questions and create new ones. The project boasts a crowdsourcing function that grants users the ability to add their materials and make revisions, which allows for an ever-expanding network of relationships.

Increasing Awareness of Pre-Modern Digital Humanities Projects

As I hope to have shown above, the digital humanities are increasingly becoming an integral part of pre-modern studies, and there are many exciting digital projects out there with the potential to change how scholars, educators, and the public think about and engage with the Middle Ages and early modern period. The projects highlighted above are only a small handful of the hundreds of pre-modern digital projects in existence or in the works.

In reviewing these projects, and in the course of my own research, I have been repeatedly frustrated by how randomly I have stumbled across these projects. Earlier knowledge of some of these digital editions and databases may have significantly altered the course of my research. While it is unrealistic to provide anything resembling a comprehensive list or catalogue of pre-modern digital humanities projects at this point, I would like to offer an early compilation of valuable databases, catalogues, and portals that link scholars to some of these projects. While the list below focuses on resources specializing in pre-modern studies, many of the resources also touch on digital humanities projects more broadly. ▍