Chancellors

-

Daniel Diermeier 2020 - Present

A visionary leader and lifelong academic, Daniel Diermeier is dedicated to advancing Vanderbilt's mission and values at every level across the university's ten schools and colleges. Born in Berlin, Germany, Diermeier is a first-generation college graduate who most recently served as the Provost at the University of Chicago. View full biography.

-

Nicholas Zeppos 2008-2019

Nicholas S. Zeppos was named Vanderbilt University's eighth chancellor in 2008. His appointment was the culmination of many years of service to the university, where he started as an assistant professor of law in 1987 and went on to serve as a professor of law, associate dean of Vanderbilt Law School, associate provost for academic affairs, vice chancellor and provost.

A distinguished legal scholar, teacher and executive, Zeppos elevated Vanderbilt's mission as a top academic research university and furthered the school's commitment to making education accessible, inclusive and immersive. Under his leadership, Vanderbilt rose from No. 19 to No. 14 on the U.S. News & World Report's ranking of best universities, and from No. 20 to No. 10 within Reuter's assessment of the world's most innovative universities.

Shortly after becoming chancellor, Zeppos implemented Opportunity Vanderbilt, a pioneering initiative that provides loan-free tuition to the nation's most talented and deserving undergraduate students, regardless of their background and financial means. Launched amid the economic uncertainty of 2008, Opportunity Vanderbilt has raised more than $400 million for scholarships and has been recognized as the nation's best financial aid program by The Princeton Review.

Zeppos was instrumental in planning and executing Vanderbilt's transformative residential college system, including The Martha Rivers Ingram Commons, Warren and Moore colleges and E. Bronson Ingram College, with three additional colleges underway and planned-all major strides toward reinventing the student residential experience to educate the whole person. His dedication to holistic living-learning programs is also reflected in Vanderbilt's FutureVU campus development plan, which aims to further position the university's campus to fully, creatively and thoughtfully advance its academic mission.

In addition, Zeppos launched the university's Academic Strategic Planning process; the development of new programs in Jewish studies, law, economics and genetics; and the effective separation of Vanderbilt University from Vanderbilt University Medical Center, a prescient restructuring that positioned both institutions for long-term success.

As a professor of law, Zeppos applied his love of teaching to his role as chancellor and champions education as the ultimate foundation for strong leadership and change for the better. An active teacher at Vanderbilt and frequent speaker throughout the Nashville area and beyond, Zeppos has received many accolades including INSIGHT Into Diversity magazine's Giving Back Award (2016), the Jack C. Massey Leadership Award from Mental Health America of Middle Tennessee (2011) and eight teaching awards, including five for "Best Professor."

During his time as chancellor, Zeppos served as the chair of the Association of American Universities Board of Directors, a role through which he further established himself as a national advocate for the importance of higher education. He was also a member of the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics and served on the boards of the Consortium on Financing Higher Education and Vanderbilt University Medical Center. He also served as president of the Southeastern Conference Executive Committee and co-chair of the United States Senate-appointed Task Force on Government Regulation of Higher Education.In August 2019, Zeppos stepped down from the role of chancellor. In November 2019, the Board of Trust voted to give Zeppos the newly-created endowed Cornelius Vanderbilt Chancellor Emeritus Chair. To honor Zeppos' commitment to the residential college model, the Board also announced that residential college opening along West End Avenue in 2020 will be named the Nicholas S. Zeppos College.

In 2020, Zeppos returned to full-time teaching and won his eighth teaching award. He currently serves as Chancellor Emeritus and Distinguished Professor of Law and Political Science Emeritus. He serves on the board of trustees of McLean Hospital, the number one-ranked psychiatric hospital in the nation and a Harvard-affiliated hospital. He also serves as a member of the Massachusetts General/Brigham Hospital Corporation.

He is married to Lydia A. Howarth, an accomplished editor. They have two sons, Benjamin and Nicholas.

Nicholas S. Zeppos

Nicholas S. Zeppos

Nicholas S. Zeppos

Nicholas S. Zeppos -

Gordon Gee 2000-2007

One of the most experienced chief executives in higher education, Gordon Gee became the seventh chancellor of Vanderbilt University on July 31, 2000, succeeding Chancellor Joe B. Wyatt. Gee previously served as president of Brown University, The Ohio State University, University of Colorado and West Virginia University. He left Vanderbilt on August 1, 2007, to return to The Ohio State University as president.

A joint-degree recipient in law and education from Columbia University, Gee completed a federal judicial clerkship, after which he served as an assistant dean for the University of Utah College of Law. After holding this position, Gee served as a judicial fellow and senior staff assistant for U. S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Warren Burger. He then became associate dean and professor at J. Reuben Clark Law School of Brigham Young University and next served as dean of law at West Virginia University. It was at West Virginia University that he made the transition from law school administrator to university president.

Upon assuming the chancellorship at Vanderbilt, Gee renewed the institution's commitment to being one of a small number of private universities that admit applicants regardless of their ability to pay and that meet the full demonstrated financial need of all students so that a Vanderbilt education is affordable to all. During his tenure, the annual budget for financial aid doubled, from $30 million to $60 million, reducing significantly the debt burden for graduating students. Applications for admission increased from 8,000 in 2000 to more than 13,000 in 2007, and Vanderbilt became one of the most selective institutions in the country, with average SAT scores rising almost 100 points and with more than 90 percent of incoming students coming from the top 10 percent of their high school classes. The university saw one of the most rapid changes in student body diversity during this time, with a 50 percent increase in minority students.

The campus landscape changed visibly under Gee's leadership, as more than $700 million in new facilities for medical research, student services, studio arts, engineering, law, children's health, diabetes care, performing arts, interdisciplinary work in arts and sciences, tennis, baseball, Jewish life and African-American culture were completed or begun. In perhaps the most dramatic development in campus life, the university began construction of The Martha Rivers Ingram Commons at Vanderbilt, a $150 million investment in the undergraduate experience that has transformed student life by creating a "campus within a campus" for first-year students beginning with the entering class of 2008.

Vanderbilt University Medical Center became the most-preferred provider of health care services in Middle Tennessee, with the opening of the most advanced children's hospital in the country and new clinical services in a number of areas.

Gee placed a special emphasis on increasing Vanderbilt's commitment to and participation within the surrounding community, specifically through the development and enhancement of world-class scholarship, teaching and mentoring, public service and patient care. While at Vanderbilt, Gee personally played an active role in the Nashville community and in Middle Tennessee. He served as a member of the advisory committee for the Nashville Alliance for Public Education and the Tennessee Campus Compact Presidents' Council. He was on the board of directors for Nashville's Montgomery Bell Academy, Harpeth Hall School, and the board of the Tennessee College Association. In conjunction with Vanderbilt, Chancellor Gee was awarded the Outstanding Promotion of Diversity Award by the Nashville branch of the NAACP. In 2004, he was a recipient of the Nashville Women's Political Caucus' Good Guy Award and the recipient of the Nashville chapter of the Public Relations Society of America's Apollo Award for Communications Leadership.

Gordon Gee

Gordon Gee

Gordon Gee

Gordon Gee -

Joe B. Wyatt 1982-2000

When Alexander Heard retired in 1982, the board named Joe B. Wyatt to succeed him. As chancellor, Wyatt sought to place Vanderbilt in the very top tier of American universities.

Wyatt, a Texan, holds degrees in mathematics from Texas Christian University and the University of Texas. He was vice president for administration at Harvard University - and father of a Vanderbilt sophomore - when he was selected as Vanderbilt's sixth chancellor. As a computer scientist and executive, he brought to the university his concept that information technology is a strategic resource of accelerating global importance in education, research and patient care.

In addition to his influence in technology, Wyatt pushed the university community to unprecedented levels of involvement in volunteer community service. Alternative Spring Break was founded in 1987 by a handful of students with Wyatt's support. It is currently the largest student-run organization on campus, sending over 400 students across the nation and abroad each March. With funding from the chancellor's discretionary fund, the non-profit Break Away: The Alternative Break Connection was founded in 1991 by Vanderbilt graduates to help colleges across the country start alternative spring breaks. Today, Break Away estimates that 350,000 students across the U.S. will participate in an alternative spring break experience.

The term "national university" took on expanded meaning under Wyatt. He led a national effort to improve elementary and secondary education in the nation's public and private schools, and made the Vanderbilt student body the most diverse in history, with minority enrollment in Vanderbilt's four undergraduate schools tripling during his tenure.

In 1989, for the first time, Vanderbilt's undergraduate programs were ranked among the top 25 national universities overall in the U.S. News & World Report survey, placing 24th. Vanderbilt continues to be ranked in the top 25.

During Wyatt's term as chancellor, the Medical Center expanded most dramatically, to account for more than 70 percent of the university's income and expenses and employing almost half of the full-time faculty, more than half of the part-time faculty and the majority of staff.

Under Wyatt, Vanderbilt acquired or built one-third of the campus - more than four million square feet of mostly new construction - and undertook one million additional square feet of renovations to existing facilities.

Wyatt spent much of the early '90s working with trustees and staff in The Campaign for Vanderbilt, which at the time was the most ambitious fund-raising effort in the institution's history. This campaign, which ended in 1995, raised $560 million. Under Wyatt's leadership, Vanderbilt's endowment grew to $1.8 billion and its operating budget grew to $1.3 billion. Sponsored research quadrupled, from $42 million to $214 million.

One of Wyatt's most significant accomplishments as chancellor was the improvement in the quality of Vanderbilt's faculty. The criteria for faculty appointment, promotion and tenure was strengthened twice during his administration, making it clear that excellence in scholarship, teaching and service are required for all members of the faculty. The number of endowed faculty chairs increased from 39 in 1982 to more than 100 when he departed, and faculty salaries continuously increased as well.

Wyatt retired as chancellor in July 2000 and was succeeded by Gordon Gee.

Joe B. Wyatt

Joe B. Wyatt

Joe B. Wyatt

Joe B. Wyatt -

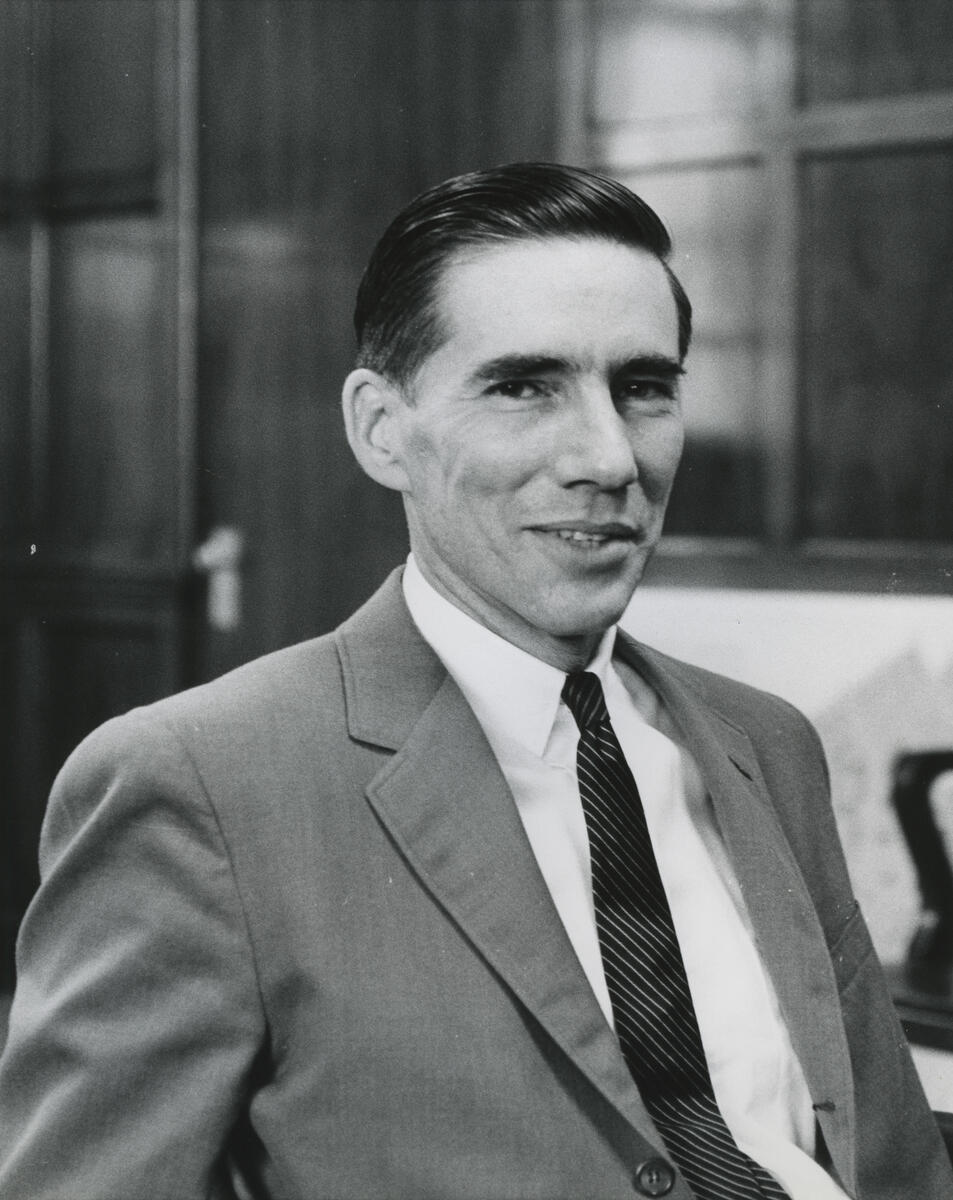

Alexander Heard 1963-1982

Before Alexander Heard was named chancellor in 1963, he was dean of the graduate school at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and had made a name for himself as a brilliant political scientist. Holding a B.A. from UNC and M.A. and Ph.D. degrees from Columbia, he had written two books, "A Two Party South?" and "The Costs of Democracy," the latter having led to his being named by President John Kennedy to serve on the Commission on Campaign Costs.

Heard guided the Vanderbilt ship through some very troubled waters. While he was at the helm, unrest engulfed many campuses across the country, at times leading to violence. Early on, Heard began holding quiet, regular meetings with student leaders, including some of the foremost campus radicals. Consequently, as far as activities on campus were concerned, Vanderbilt witnessed peaceful demonstrations, and Heard's defense of the open forum survived challenges from both ends of the political spectrum.

Another segment of the Heard legacy was his successful effort to place the first woman, Mary Jane Werthan, B.A. '29, M.A. '35, on the board. He also convinced the board to create a new class of trustees- four recent graduates-to assure a youthful perspective would be heard by the board- one of the first universities in the nation to do so.

Beginning in 1974, Heard laid careful plans to undertake a historic campaign for the university to raise $150 million. From 1977 through 1981, he stumped for contributions by traveling 117,537 miles, visiting 60 cities in 25 states. When it was over, the campaign had raised $180 million, $30 million above the goal.

Some of those funds were designated to build a home for the growing graduate school of management. The board had first discussed such a school during World War II, and the idea had grown slowly. With new funds available, Heard was able to announce that work had begun on a $6.7 million building for the Owen Graduate School of Management, named for two local benefactors, Ralph and Lulu Owen.

Finally, in 1979, after a challenging and difficult set of negotiations involving Heard and others, Vanderbilt and Peabody College merged. Two years later the Blair School of Music merged with Vanderbilt. In 1983 the board recognized Heard's work in building the university community by naming the Vanderbilt library system for Heard and his wife, Jean.

Heard had inherited a university with seven schools; by the end of his tenure as chancellor in 1982, Vanderbilt's current complement of 10 schools was in place. When Alexander Heard retired in 1982, the board named Joe B. Wyatt to succeed him.

Alexander Heard

Alexander Heard

Alexander Heard

Alexander Heard -

Harvie Branscomb 1946-1963

Born in Huntsville, Ala., Harvie Branscomb, the son of a Methodist minister, earned his B.A. at Birmingham Southern and a distinguished M.A. in biblical studies as a Rhodes Scholar. After working on the same Hoover relief commission as Oliver Carmichael, he served in the Army and then took a professorship at Southern Methodist University before earning a Ph.D. at Union Theological Seminary and Columbia University. The 51-year-old dean of the divinity school at Duke University was named Vanderbilt chancellor in 1945.

In his 17 years as chancellor, Branscomb directed an expansion of Vanderbilt that resulted in a doubling of the number of buildings. Perhaps more important than the expansion of facilities, however, was the expansion of Vanderbilt's vision of what it could become. Not satisfied with Vanderbilt as a great Southern university, Branscomb wanted Vanderbilt to become a national leader among universities.

The chancellor knew that Vanderbilt must be open, not only to all types of ideas, but also to all types of people. He stressed the idea that Vanderbilt could not hope to become a true national university unless it was willing to make changes, and that meant dealing with racial integration at a time when higher education in the South was strictly segregated.

First, Branscomb explained to the Board of Trust that Peabody College had admitted two African Americans and, unless the board wanted to break a long-standing cooperative agreement with Peabody, Vanderbilt would have to allow the students to take Vanderbilt classes.

A few meetings later Branscomb was back, explaining that he was confronted with the case of a black minister from Jackson, Tenn., who wanted to take courses at the divinity school. After all, the chancellor said, it would look bad to turn down a minister.

Then, a little later, the chancellor explained that because of a new position taken by the American Association of Law Schools, Vanderbilt's law school might lose its accreditation if it didn't admit African Americans. Later, he explained that the university in general was in danger of losing foundation support if it did not admit more African Americans.

All the while, Branscomb was subtly encouraging the Faculty Senate to vote overwhelmingly in favor of integration, nudging student groups to speak out. One of his allies was the editor of the "Vanderbilt Hustler," who campaigned for open admissions. That editor was a student named Lamar Alexander, who would later become governor of Tennessee and then U.S. Secretary of Education.

Branscomb is credited with transforming the selection process for nominees to the Board of Trust in order to attract leaders of national as well as local institutions. He recruited Harold Stirling Vanderbilt, great-grandson of founder Cornelius Vanderbilt, to membership on the board. In an effort to recruit and retain distinguished scholars and scientists to the university's faculty, Branscomb urged the board to reinforce the university's commitment to academic freedom, raise faculty salaries and recruit distinguished faculty.

Despite the discord caused late in his administration by fallout from the expulsion for civil disobedience of black divinity student James Lawson, by the end of his chancellorship, Branscomb had guided Vanderbilt to an open admissions policy, constructed vastly improved facilities, and laid the foundation for a national reputation, including election to the elite American Association of Universities in 1949. Branscomb retired in 1963, and the board named Alexander Heard, 48, as chancellor.

Branscomb lived another 35 years, dying on July 24, 1998, at the age of 103. He maintained an office in Kirkland Hall until his death, and until shortly before he died, regularly attended university functions.

Harvie Branscomb

Harvie Branscomb

Harvie Branscomb

Harvie Branscomb -

Oliver C. Carmichael 1937-1946

To replace James H. Kirkland, the board named Oliver C. Carmichael, 46, then dean of the graduate school at Vanderbilt. This signaled a turning point for the university because Carmichael already had shown that he favored an institution more attuned to current problems than the older, more elitist Vanderbilt. As dean, he wanted more emphasis on graduate work and research and a more flexible curriculum.

These changes were opposed by many of the older faculty. Despite a protracted fight, Dean Carmichael backed down and saw few of his changes become reality.

After 1937, however, he had the big stick of the chancellorship. He proved to be a consummate politician, and in time he achieved most of his changes through persuasion rather than coercion.

Carmichael grew up on an Alabama farm. He graduated from Alabama Presbyterian College, received a master's degree at the University of Alabama, then was awarded a Rhodes scholarship. While Rhodes Scholars at Oxford, Carmichael and a fellow student, Harvie Branscomb, were among a group of American student volunteers who worked for Herbert Hoover's Commission for Relief in Belgium. For smuggling a politically sensitive letter from Cardinal Mercier through the German lines, the two were awarded the Medaille du Roi Albert, Medaille de la Reine (Belgium). Their friendship would shape Vanderbilt's destiny for nearly three decades.

After working as a YMCA employee in India and East Africa and doing a stint in the U.S. Army, Carmichael came home to be principal of a high school and later president of Alabama College, a small women's college.

Carmichael had an engaging personality and had become widely known in Southern academic circles as an expert on educational philosophy. These factors led to his being tapped to head the new graduate school at Vanderbilt.

Later, as chancellor, Carmichael's political skills resulted in what may be the greatest single achievement of his administration, the establishment of the Joint University Libraries serving Vanderbilt, Peabody and Scarritt College.

In 1945 Carmichael resigned to become head of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. The Vanderbilt board, following a lengthy search, picked a 51-year-old biblical scholar named Harvie Branscomb, then dean of the divinity school at Duke University.

Oliver C. Carmichael

Oliver C. Carmichael

Oliver C. Carmichael -

James H. Kirkland 1893-1937

James H. Kirkland, just 34 years old when he became chancellor, hailed from South Carolina. The son of an itinerant Methodist preacher, he attended Wofford College then received his Ph.D. at the University of Leipzig. With the help of colleagues he met during his German studies, he landed a job teaching Latin at Vanderbilt in 1886.

Kirkland remained in the post for 44 years, dealing with financial problems-the Methodist church was proving to be long on criticism and short on financial contributions-and fostering a number of projects designed to raise educational standards in the South.

One of the biggest challenges Kirkland faced in his tenure occurred at 11 a.m. on April 20, 1905. Fire broke out in Old Main, the heart and soul of Vanderbilt life. Throughout the afternoon, while the fire raged, students threw books out the windows. Students waiting below caught the books and carried them to a safe place. Before the fire finally gutted most of the building, students had saved 4,000 books; another 18,000 books burned.

Before the day ended, Chancellor Kirkland posted a letter to the anxious student body. Do not brood over this calamity, he wrote his charges, move on and look to the future. He assured them the academic program would continue. Indeed, students assembled the next morning in makeshift classrooms across campus. Not one class was cancelled. In the months ahead, Kirkland took the sow's ear of a fire and turned it into a silk purse of unprecedented new giving to the university, giving prompted in large part by the alumni's desire to help rebuild that cherished building.

In 1910 open warfare broke out between the Vanderbilt administration and the Methodist church. The bishops opposed Kirkland's attempt to swap some land with Peabody College. Kirkland, in turn, opposed the bishops when they pushed to retain the right to name members of the Vanderbilt board. The campus strongly supported the chancellor. Finally, in 1914, the Tennessee Supreme Court ruled against the bishops and the university's separation from the church was complete. Some 1,000 students, with Chancellor Kirkland leading them, marched in celebration through downtown Nashville.

Kirkland enjoyed golden years from 1916 to 1929. One of his major triumphs was the relocation of the School of Medicine to the main campus and the construction of a facility in 1925 to join under one roof the medical school's laboratories and its teaching hospital. In order to build that facility, the chancellor led a drive to raise more than $5 million, an immense sum at the time. The Rockefeller Foundation and the General Education Board also provided funding to build the full-time, research-oriented medical school dedicated to specialized scientific research and public health outreach-a medical school unlike any other in the South at that time.

Kirkland retired in early 1937 and the board named Oliver C. Carmichael to replace him as chancellor. Kirkland died two years later while vacationing in Ontario. As a tribute to the years he spent building the university, Old Main was renamed Kirkland Hall.

James H. Kirkland

James H. Kirkland

James H. Kirkland -

Landon C. Garland 1875-1893

The first chancellor, Landon C. Garland, was a Virginian and hugely proud of it. He earned a B.A. from Hampden-Sydney in 1829, taught at Washington College, then at Randolph-Macon. One of Garland's pupils in those days was Holland McTyeire. By the time young McTyeire graduated in 1847, Garland was president of Randolph-Macon, and it was he who handed McTyeire his diploma. Their paths would cross many more times.

Following the Civil War and after several years as president of the University of Alabama, Garland took a position at the University of Mississippi. It was here that McTyeire, now a Methodist bishop, sought out his former teacher and enlisted him in the campaign to build a Methodist university in Nashville. Garland, the most highly respected academic in Southern Methodism, wrote essay after essay in church publications on the need for an "educated ministry." With Garland onboard, the bishop now needed the money-for that, he turned to Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt.

Garland, named early on as the first chancellor of Vanderbilt University, had some definite ideas about the rules that would govern the university's place in this world. Under Garland's plan, Vanderbilt would have four departments: Biblical; Literature, Science and Philosophy; Law; and Medical.

Though Bishop McTyeire usually was there looking over his shoulder, Chancellor Garland clearly set the mood of the campus. Steeped in Scottish moral philosophy, Garland believed that the development of character was the central purpose of a true university. He did his part to mold character each Wednesday when he preached sermons to the student body in chapel, and he was staunch in his opposition to dormitories, claiming they were "injurious to both morals and manners."

In the early days, the closest thing to campus radicals were the law students. In fact, the law students provided the first challenge to a chancellor over the concept of an open forum. Garland had invited John Sherman, brother of Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, to address the students in chapel. For the law students, it was more than they could bear to sit through a speech by the brother of the Yankee general who had burned a wide swath from Atlanta to the sea. The law students held a protest meeting, then marched single file out of the building, some playing Dixie on their harmonicas.

In 1889 Bishop McTyeire died. Two years later Garland tendered his resignation to the board of trustees, but they kept it in abeyance until 1893 when the board named as chancellor James H. Kirkland.

In the end and to this day, McTyeire's and Garland's bones lie side by side in a grave on the Vanderbilt campus.

Landon C. Garland

Landon C. Garland

Landon C. Garland

Landon C. Garland