Organic Chemistry II: NMR Spectroscopy Module

Emilianne McCranie, Chemistry, working with

Michelle Sulikowski, Senior Lecturer in Chemistry

Overview

Organic chemistry is primarily a problem-based discipline. As such, it seems particularly well-suited to a flipped-classroom model, in which material traditionally found in lectures is presented outside of class and classroom time is reserved for working through problems.

We implemented the flipped classroom model in response to evidence of students’ struggling with the concept of nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR) in an undergraduate organic chemistry course. We have seen that the theory behind NMR can be difficult to grasp solely from lectures and static representations.

Therefore, we experimented with a flipped classroom method for a weeklong module on NMR spectroscopy, making short video lectures available to the students before class as homework and spending class time on problem-based learning.

Our learning objectives for the module were for students to be able to:

- Explain how nuclear spins are affected by a magnetic field

- Predict the number of proton signals expected from a compound given its structure. This involves identifying enantiotopic and diastereotopic protons.

- Interpret and predict simple and complex splitting patterns

- Predict chemical shift trends

- Assign peaks in an NMR spectrum to specific protons in a compound

- Interpret integration of NMR spectra

- Use J values to predict geometric isomers

- Determine the structure of a compound using NMR, given other pertinent information such as molecular formula

To deliver the pre-class work, we set up a WordPress-based website. The welcome page for the website provided an introduction to the module and provided information about what to expect and how to prepare for each of the three instructional days associated with the module:

Strategic use of online tools and assessment of students learning

We introduced course content through short videos (≤10 minutes) that were a combination of digital animation with narration, tutorial-style screen-capture, and picture-in-picture instructor description. We chose to use these approaches to directly target difficult concepts with approaches that would allow students to visualize the phenomena while maintaining a personal instructor presence.

In class, students would work in small groups to do problems such as the one shown here

These in-class workshops provided an opportunity for formative assessment, allowing both the instructor and the students to determine how well students were progressing toward learning goals.

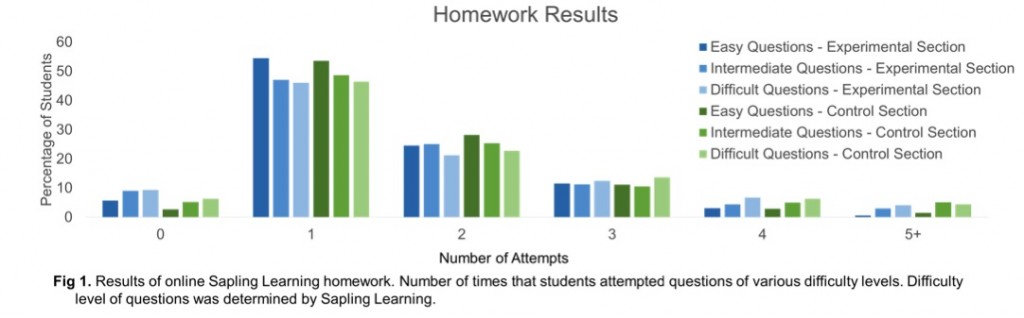

Students also completed homework problems using the Sapling learning platform. This tool allows students to have multiple attempts to complete a problem, giving them an opportunity to gain feedback and learn from their mistakes. The instructor can also examine the number of attempts required for different problem types to determine points of difficulty.

.

Evaluation of student learning and perceptions of the “flipped” module

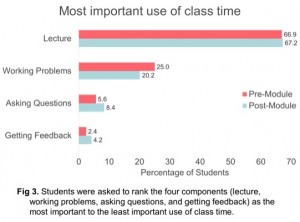

To evaluate the module, we administered pre-module and post-module attitude surveys using GoogleForms, as seen on the left.

We also used students’ performance on online homework problems via Sapling Learning, comparing students in the “flipped” section to a control section that was taught in a traditional lecture style. Specifically, we looked at the number of attempts that were required for students to achieve a correct answer.

Surprisingly, there was no significant difference between the control and experimental groups indicating that the flipped classroom module did not lead to an improvement in student learning. This result is in contrast to the literature, which shows that active learning techniques improve student learning. Perhaps looking at different data such as exams and or stratifying the students in our analysis would have revealed an improvement in student learning.

.

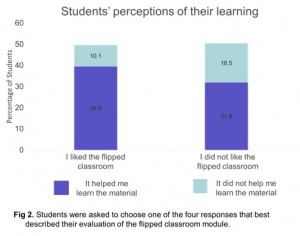

Our surveys that were designed to assess student perceptions of the module indicated that overall students did not like the flipped classroom model in an Organic Chemistry course. As this was the second semester of a two-semester sequence, students’ expectations and resistance to the different instructional technique could also have played a role.

Visit the Organic Chemistry II Web page for more information and to view more videos or see Emilianne’s poster.