[Download a PDF file of this essay here]

Nine spirited women leave Punta Arenas in August 1909 to sail to the shores of Antarctica. Their initial goal is relatively modest: observe and explore, perhaps see a little more than other people have seen before, enjoy each other’s company. They disembark their vessel close to where Captain Robert Scott landed in 1902 during his largely unsuccessful Discovery Expedition. Once their feet hit the ice, however, these nine women change their minds. They set out to travel south, reach the pole against all odds and years before any other expedition, then return to their base camp and ultimately their homes in Argentina, Chile, and Peru.

Ursula Le Guin’s short story “Sur,” first published in 1982 in The New Yorker, offers a speculative rereading of traditional accounts of polar exploration. It not only joyfully replaces dominant images of audacious men fighting the elements to conquer the poles, but also questions the value of recording, publicizing, and thereby monumentalizing such geographical pursuits. Berta, one of the members of this curious expedition, at some point builds a makeshift studio below the surface of the ice to create a series of ice sculptures. Some of them blend “the reclining figure with the subtle curves and volumes of the Wedell seal.” (1) All of them are bound to stay in place, unseen and unappreciated, because their medium—frozen water—resists future exhibitions up north. Later, the story’s narrator will decide to hide her very report in a leather trunk in the attic of her house, unwilling to broadcast her and her companions’ accomplishments. The point of the nine women’s journey to the pole, it turns out, is not to subdue the land and imprint lasting signatures for future mapmakers. It instead is to probe modes of moving and being in the world that leave as few footprints as possible. It is to navigate inhospitable territories primarily for the sake of learning how to respect the irrevocable entanglement of things human and nonhuman.

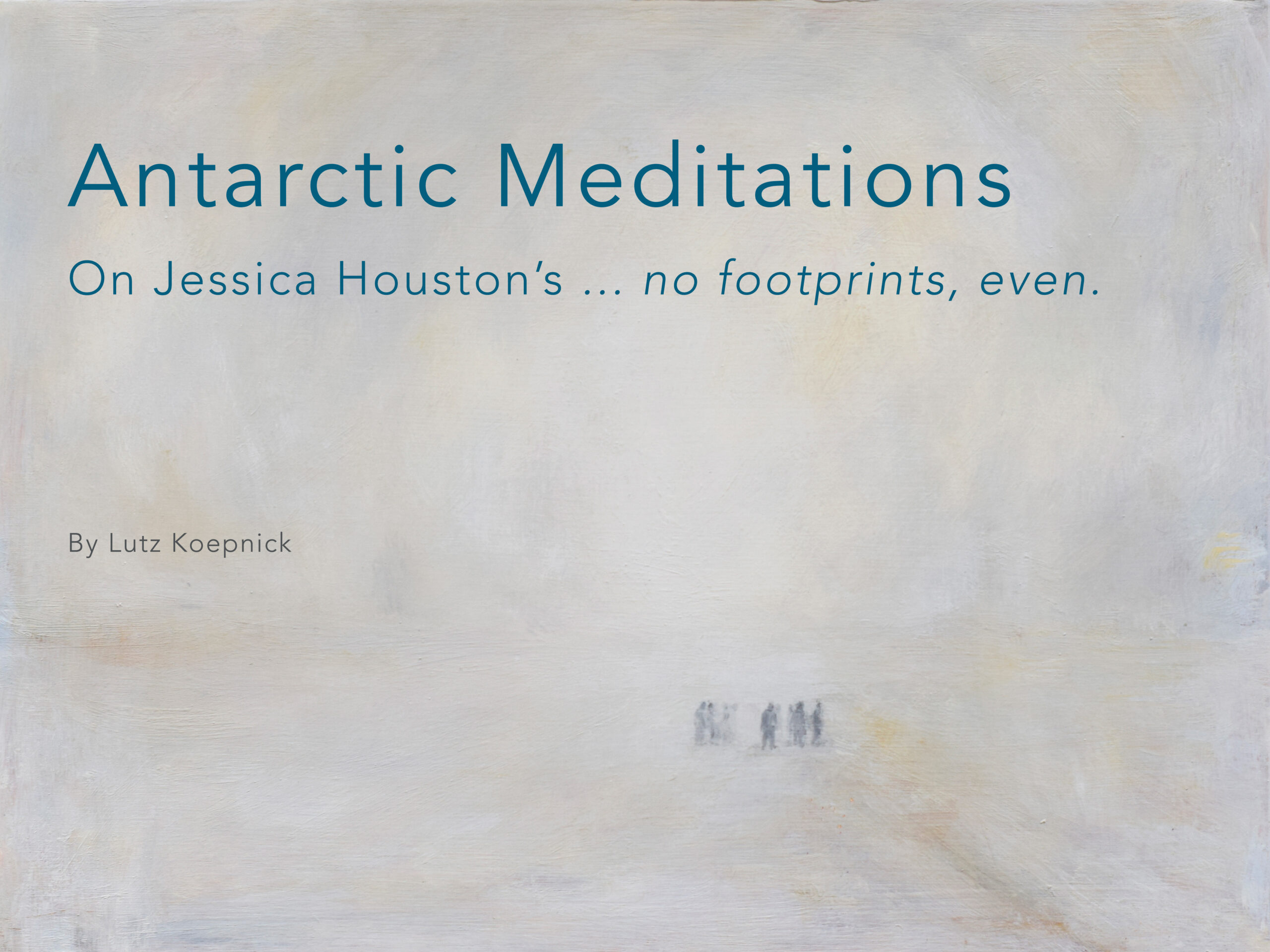

The themes in “Sur” have played a crucial role in Jessica Houston’s artistic practice over the last years, guiding different bodies of work like the needle of a compass. As if trying to emulate the curious ambitions and largely invisible tracks of Le Guin’s fictional nine women, Houston has entrusted glaciers in Antarctica to deliver unread messages to unknown readers in the future (Letters to the Future, 2019-3019). She has painted polar landscapes with brushstrokes whose delicate nature emulates the fragile nature of ice in times of climate change, but also recalls the playfulness of Le Guin’s polar travelers (The Yelcho Expedition to the Antarctic, 2022). In other series of works, Houston cuts up images from popular magazines (Over the Edge of the World, 2022) or speculates about the history of magnetism in science, art, and spiritualism (The Magnetic Observatory, 2022) to derail the enduring rhetoric of masculine heroism and colonial conquest and—like Le Guin’s fearless party—search for alternate ways of knowing and engaging with the natural world. “We left no footprints, even,” Le Guin’s narrator concludes her report about the nine women’s journey to the pole. For Houston, these final five words define a unique opening and challenge, not only to untether images of the polar region from the lasting legacies of imperialism and extractivism, but also to rethink the role of art and its own footprints amid contemporary conversations about climate change.

Artistic practice, in our age of highly mediated untruths and data-driven parochialisms, has the prerogative to ask big questions to which easy or unambiguous answers may neither be possible nor even desirable. Houston’s transdisciplinary takes on Antarctica truly live up to this. What holds this work together are three rather large and daring questions: How can contemporary art decolonize historical narratives of exploration and unsettle continued efforts to employ science and image-making as tools of territorial conquest and extraction? What can art do to reveal the slow temporalities and deep histories of geological processes so as to retune the damaged relationships between human and nonhuman entities on this planet? And finally, more self-reflexively: How can artistic practice today, true to the environmental ethics of Le Guin’s protagonists, leave as few footprints as possible and hence stray away from art history’s own logic of extractivism, its incessant preoccupation with artistic signatures, physical objects, lasting marks, collectible things, and shiny exhibition venues?

If you look for explicit answers to these questions in the materiality of Houston’s brushstrokes, the documentary quality of her photographs, or along the cuts of her at times irreverent, at times outright hilarious collages, you look in the wrong place and, as Houston’s Letters to the Future suggests, use an inappropriate timescale. Whatever qualifies as a possible answer instead resides in this work’s very journey and ongoing movement, in how Houston seeks to open the viewer’s eyes, ears, and minds to the pluritemporal lives of the ice itself, its memories, its ever-changing materializations of time, its distressed existence under the impact of human-induced planetary change. For Houston, the question—the journey—itself is the answer. It emerges in ever-different shapes and forms from her ambition to probe non-extractivist ways of engaging with what exceeds our grasp. It manifests itself in how her work perturbs our desire to get a hold of things in the form of timeless images, scientific formulas, and individual property claims.

“A glacier,” writes journalist and environmental advocate Dahr Jamail, “is essentially suspended energy, suspended force. It is time, in that sense, life, frozen in time. But now, these frozen rivers of time are themselves running out of time.” (2) Houston’s polar meditations suggest that Jamail is both right and wrong. Yes, Houston’s journeys across different artistic media and polar landscapes insist that ice is life and energy, owns some form of agency, and bears the right to have rights. But no, she adds, to think of polar glaciers, ice sheets, or ice caps as life frozen in time misses the point, whether or not we are looking for reliable benchmarks to reveal environmental degradations. Ice never sleeps. It never rested even before fossil fuel economies began to warm the planet. Ice appears still and suspended only if you pivot concepts of change around human timescales and agendas, our modern impatience and temporal short-sightedness. Ice only seems or should seem timeless if you elevate the logic of human exceptionalism to how you understand the world in general and thereby merely reiterate what the Scotts, the Shackletons, and the Amundsens have being doing all along.

The point of Houston’s open-ended inquiry into Antarctica’s pasts, presents, and futures is not to freeze or refreeze its icy landscapes in the hope of reclaiming the incompatibility of human and nonhuman temporalities. On the contrary, what moves her work is her determination to question ingrained divisions of nature and culture and, like Le Guin’s Berta, probe possible resonances and synergies between human and nonhuman forms, between what is us and what isn’t, between our own rather time-less itineraries and the many voyages of ice in all its different states and shapes, its timefulness. (3) Think like Antarctica, Houston urges her viewers: try to sense time through the unsteady medium and membrane of polar ice.

***

One among many ways of doing this might start with recognizing that sometimes doing nothing is better than doing something.

In 1997 Belgian artist Francis Alÿs spent an entire day pushing a weighty block of ice through the streets of Mexico City until none of it was left anymore, calling his performance Paradox of Praxis 1 (Sometimes making something leads to nothing). In 2022, as if to invert Alÿs’s non-intervention, Houston created a series of small paintings based on magnetic drawings and diagrams from the ancient to the contemporary world. Gathered under the title The Magnetic Observatory, Houston’s square canvases feature abstract shapes, playful geometries, vibrant lines, and luminous colors. Each of them aims at indexing Earth’s invisible magnetic forces within the defined space of eighty-one square inches. What they altogether probe, however, are the paradoxes of human action in a world of human-made crisis, following Lao Tzu’s reflections on the value of non-doing, as translated into English by none other than Ursula Le Guin: “Those who think to win the world / by doing something to it, / I see them come to grief. / For the world is a sacred object. / Nothing is to be done to it. / To do anything to it is to damage it. / To seize it is to lose it.”

Magnetism has a curious history. Ancient Greek philosophers studied it to find evidence for the animated nature of all matter, the hidden life of rocks and minerals, the many souls and spirits that enveloped human existence on Earth, invisible yet full of impact. German mystics in the late eighteenth-century spoke of animal magnetism, claiming that creatures and plants owned energetic life just like human beings. The name of the movement’s leader, Franz Mesmer, eventually transformed into a verb to describe processes of re-enchantment amid a perceived world of modern scientific hubris, soulless technology, and calculating reason. Though later challenged as inaccurate and dilettantish, Captain Scott’s investigation of magnetic forces during his Discovery Expedition between 1901 and 1904 opened a critical window for modern scientists to understand the complex functions of Earth’s magnetic field—its convergence at the planet’s poles, its ability to guide the movements of animals and compass-equipped humans, and its crucial role in protecting our planet’s atmosphere from harmful radiation.

In Houston’s series of paintings, magnetism allegorizes not a conflict between incompatible modes of understanding life on Earth, but a rather joyful coming together of science and spiritualism, age-old cosmologies and modern needs for navigational orientation, desires for physical protection and for metaphysical connection. Most of all, however, in presenting her canvases as echo chambers of invisible waves and geological forces, Houston’s Magnetic Observatory takes on the central challenge of Lao Tzu and Le Guin’s antiheroic travel narrative: how can we be in and of the world without shaping this world unduly in our own image? Unlike willful explorers who seize the land by leaving marks and footprints, The Magnetic Observatory responds to this question by seeking to practice the art of radical receptivity, of unconditional openness to the visible and invisible dynamics that surround us. At once radiant and contemplative, these images explore the wonders of co-existing with what is not of our own making and exceeds our control. They approach the elements—magnetism—as something that can mesmerize our attention precisely because it transcends our senses and interferes with our existence whether we want or know it or not.

Catastrophic weather events today offer unmistakable signs that the inhabitants of Earth’s Global North have overstretched our planet’s hospitality, the Holocene’s generous geological and atmospheric conditions. Following the faint footprints of Le Guin’s work, The Magnetic Observatory turns the tables on this failure. With their pulsating colors, energetic shapes, and dynamic lines, each of these images gestures toward a dire need to reorient our understanding of self-determination and hospitality amid our inhospitable times. As they register what often eludes human perception and evidential reasoning, Houston’s magnetic paintings remediate our fear about what is beyond our grasp and invite the unknown, the invisible, to enter the bubbles of our dwellings. In this, each of these images presents playful exercises in unconditional hospitality. They hone our readiness to welcome what is not us, precisely because, in Lao Tzu’s Taoist words, no one will ever win the world in all its material and immaterial entanglement anyway.

Sometimes, The Magnetic Observatory tells the viewer, doing nothing indeed leads to something. Like Alÿs’s 1997 performance, these humble and ecstatic paintings toy with the paradoxes of practice in our damaged, human-centered world. They invite the viewer to become the very ice our carbon footprints increasingly turn into water. Retune your credos of doing, shaping, measuring, extracting, and trading, these images urge their viewers. Amend the dogmas of productivity, busy-ness, and progress that have generated your present emergencies in the first place and have eviscerated your ability to be mesmerized by anything that is not of your own making. Be the ice you force to melt at accelerated speeds. And then, take things from there.

***

Held close to the ear, melting pieces of ice tend to snap, crack, and pop as they release bubbles of air from prolonged periods of capture. Torn away from floating icebergs and continental ice shelves, chunks of drifting sea ice do the same. They intone symphonies without score, compositions that elude known keys and meters. What you truly hear, however, is this: the sound of distant pasts, of air popping back into the open after many millennia of detainment. This is music that results from extended time travel. Twisted songs of liberation, if you wish. Sounds produced by planetary deep time that cannot but humble ordinary human ears as much as a musicologist’s vocabulary.

Houston doesn’t shy away from taking collaborators and viewers on similar journeys through time and approaches our very present through the lens of geological deep time. Think of Letters to the Future, a project that started in 2019 and is anticipated to come to its conclusion sometime around 3019. Literally moving at the speed of ice, Letters to the Future is time-based art at its most startling and humbling. It lives in and with extended durations, and as such it hopes to save time in equal measures from our restless grasp for short-term gain and compensatory dreams of timelessness.

A small tube, buried deep in the ice of an Antarctic glacier, will travel for a projected period of 1,000 years to reach the open sea. It contains messages no one except their authors have seen, not even Houston herself, the tube’s dispatcher. Philosopher Rosi Braidotti, poet Anne Michaels, theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli, Inuit politician Okalik Eegeesiak, and Estonian composer Arvo Pärt contributed to this project, as did the South African artist duo Rosenclaire, the climatologist Gavin Schmidt, and Houston’s twin daughters Rose and Zoé Tremblay. Sealed and shipped in 2019, their messages were penned to address a distant and unknown future, assuming anyone might still be around to read and decipher these missives in the third millennium. And yet, deep down, they address none other than us—today, right here, right now. Taken prior to their departure, Houston’s images of their signed envelopes ask us to ponder how tomorrow’s world will think about what we have done to our planet. And about what we have not done to ensure that polar ice doesn’t break off Antarctica, like the Brunt ice shelf in March 2021, or the Conger ice shelf in March 2022, both substantially larger than New York City.

Art is a verb and not a noun, many rightly claim to prioritize process over product, the transformative qualities of aesthetic experience over any effort to own and trade individual works like profitable investments. But there is for sure no proper grammatical tense or mood, at least in English, to conjugate the verb that is Houston’s Letters to the Future. To make its case, the project neither draws on the “what if” of the subjunctive, nor does it appeal to the retrospective closure of the future perfect. Instead, it cuts across any of the neat distinctions most widely spoken languages put into play to make time manageable. Much to the viewer’s conceptual bewilderment, Letters to the Future showcases the limits, the insufficiency, of most human languages to live up to the durational extension and plurality of planetary history. The future here impacts the present as much as missed opportunities of the past shape how we understand the now. Whatever we call the present is never more and never less than a messy meeting ground of different streams of time, pluralistic memories and speculative anticipations, unfinished stories and countless stories-to-be-told.

Like the sealed letters embedded in the Dronning Maud Land ice sheet, the time and life of ice in Houston’s work resist linguistic capture and conquest, our self-absorbed drive to leave linguistic footprints. Ice might move and transform at rates invisible to the human senses, often leading us to think of it as analogue to the medium of photography, not of film. In truth, however, ice—according to Houston—is much more than a mere representation or image of time. It is time itself, a clockwork with many hands. It is a verb. It is migrant, as Chilean poet and artist Cecilia Vicuña would say. (4) It is a medium that, according to John Durham Peters’s definition of elemental media such a clouds, rivers, and air, provides a vessel and environment, a conduit at once anchoring and enabling the multitude of lives on Earth. (5) And as such, whatever it does and displays, Houston’s ice is simultaneously timely and untimely, speaking languages far more complex than what most human grammars can communicate. It is past, present, and future folded into one. Or perhaps something fourth altogether.

A glum German philosopher once considered art and modern music “the surviving message of despair from the shipwrecked.” (6) Houston’s unseen and unheard messages, as they slowly travel with the ice in their own kind of bottle, are much more optimistic in nature. Despite omnipresent signs of environmental degradation, in addressing future readers these missives insist on the possibility that the future has a future. While they remind us of our obligations toward upcoming generations, they also acknowledge the fact that planet Earth will certainly heal in the long run whether humanity will make it or not. Houston here approaches ice not simply as an object of representation, but as medium and collaborator, well aware that its popping sounds will remain part of the planet’s playlist long after our species’ demise. Despair and melancholic grief, according to Houston, formulate strangely anthropogenic and narcissistic responses to the most pressing challenges of the Anthropocene. Shipwrecked we might be. At the end of time we are not.

***

To follow Houston’s subtle paths across Antarctica is to learn languages whose syntaxes shun our modern desire for temporal linearity, development, and progress. When seen from the standpoint of planetary history, ice always moves, flows, and transforms. But it resists any effort to organize time into orderly narratives with clear beginnings and meaningful endings, distinct chapters, ruptures, and resolutions. And for this reason, it also encourages us to reframe the very stories we tell to chronicle the history of art and its many representations of the polar regions.

Western art, film, and photography abound with images depicting the Arctic and Antarctic as geographies of the sublime—glacial landscapes that either serve as backdrops to gestures of individual bravery, endurance, self-assertion, and (primarily: male) bonding, or showcase the folly and fragility of any human endeavor. Rugged men with furry hoods. Other rugged men pushing sleighs through impenetrable blizzards. More men, usually white, usually bearded, erecting flags to mark their presence for the record. Capsized ships, arrested amid towering icebergs and fragmented ice shelves. And yes, deranged penguins that, at least according to one rather unreliable observer, walk off into certain death, warning foolish men not to do the same.

In her recent book Climate Change and the New Polar Aesthetics, Lisa Bloom offers abundant examples of contemporary projects that run up against these tropes of polar art. Discussing works, films, performances, and interventions of inspiring artists such as Anne Noble, Judit Hersko, Connie Samaras, Isaac Julien, Zacharias Kunuk, Kimi Takesue, Urusla Biemann, and Brenda Longfellow, Bloom maps the emergence of a new polar aesthetic eager to break away from the legacy of colonialism. "The new polar aesthetics,” Bloom concludes, “is activist, progressive, antiheroic, and earthbound (humble and rooted in the ground), and often done collaboratively with local and international publics in mind, without the goal of monetary gain. Such generous and generative art plays a fundamental role in connecting and empowering the transnational climate movement." (7)

Houston’s extensive work on the polar regions clearly fits this bill. Like Le Guin’s Berta and many of Bloom’s artists, Houston approaches the ice as kin and collaborator, as a tenuous medium of artistic practice that helps reorient our relation to land and atmosphere. Taking her cue from the traceless narrator of Le Guin’s “Sur,” Houston pushes against extractive uses of the polar regions, whether these include the potential mining of rare earth metals for “renewable” energy consumption in the Global North or the stream of well-meaning ecotourists in polar zones to get a final glimpse of their melting wonders. Houston’s art is engaged art, it is political, but not because it privileges message over form or activist intervention over aesthetic experimentation. It is political and hence an exemplary representative of Bloom’s new polar aesthetic precisely because it is all about humbly exploring the very limits of artistic representation, that is, art’s unique powers to make us recognize our smallness within the larger order of things and undo self-aggrandizing concepts of modern development. The medium itself—frozen water in Letters to the Future, electromagnetic waves in The Magnetic Observatory—is Houston’s message.

More is at stake, though.

Much of activist or political art, as we have come to know it during the twentieth century, rested on the idea that human subjects, in making history, made and marked time. History confronted us with problems, with intolerable asymmetries of social justice and power, to which art provided compelling answers, perhaps even transformative solutions. Houston’s art on ice moves the viewer beyond this tradition. In expanding the timeframes and grammars of contemporaneity, projects such as Letters to the Future and The Magnetic Observatory question that sense of unfettered human agency and makeability, the entrepreneurial logic and busy solutionism that has driven our modern age as much as its arts. For Houston, whatever we call history conjoins many different stories and durations—human, geological, biological, and planetary in nature. It never simply moves into one direction. It instead evolves in often inscrutable patterns of mutual interference and symbiotic codependency. The new, including Bloom’s new polar aesthetic, is therefore never as new and the old never as old as we so often want them to be. To think otherwise would simply repeat what led men to leave footprints on the ice in their assertive hope to control the elements—and what motivated overconfident modernists to leave marks on paper or light-sensitive materials, believing that in capturing the world they could single-handedly transform it.

Projects such as Letters to the Future or The Magnetic Observatory explore resonances between visible and invisible geographies without relying on the comforts granted by modern compasses. These works expand our frames of perception and knowledge, not for the sake of expanding the domains of human action, but on the contrary, to question our pernicious hunger for dominating the elements and our modern effort to subject nonhuman temporalities to the Global North’s extractive timetables. To think like ice is to retune the medium of time and how it structures most of our stories. It asks us to tell histories of modern life and art that no longer center around captivating figures and footprints of radical newness, shock, and originality. At heart, Houston’s polar aesthetic encourages us to dial down the art world’s own hunger for unique traces and muscular egos, its noisy, attention-grabbing, and time-less cult of rupture and innovation, the first and the foremost, the latest and the last.

“Those landscapes are remarkable,” Houston said about Antarctica in 2023, “the physicality of them, the luminosity, the beauty, the changeable state of water and ice in their interaction. I think there's just something incredibly mesmerizing and captivating about that.” (8) Le Guin’s nine women, as they travel to the pole, decide to walk lightly, and leave as few footprints as possible, would certainly agree. Beauty and awe are far from merely marking the beginning of terror. Today, we might need their counsel as never before to save the entangled nature of time, life, and art on this planet from the grasp of modern extractivism, its relentless will to win, and its devastating history of losing the world.

Notes

(1) Ursula K. Le Guin, “Sur,” in The Compass Rose: Short Stories (Toronto: Bantam Books, 1983), 239.

(2) Dahr Jamail, The End of Ice: Bearing Witness and Finding Meaning in the Path of Climate Disruption (The New Press, 2019), 9.

(3) I am borrowing the concept of “timefulness” from the captivating writing of geologist Marcia Bjornerud, Timefulness: How Thinking Like a Geologist Can Help Save the World (Princeton University Press, 2018). See also Jenny Odell, Saving Time: Discovering a Life Beyond the Clock (Random House, 2023).

(4) Cecilia Vicuña, “Language is Migrant,” in Cecilia Vicuña: Seehearing the Enlightened Failure, ed. Miguel A. López (Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art, 2019), 337-341.

(5) John Durham Peters, The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media (University of Chicago Press, 2015).

(6) Theodor W. Adorno, The Philosophy of Modern Music, trans. Anne G. Mitchell and Wesley V. Blomster (Continuum, 2007), 39.

(7) Lisa E. Bloom, Climate Change and the New Polar Aesthetics (Duke University Press, 2022), 198.

(8) Jennifer Gutman and Lutz Koepnick, hosts, Art of Interference: A Podcast on Art and Climate Change, “Ice,” season 1, episode 7, July 27, 2023, 41 min., 12 sec., https://artofinterference.com/episodes/s1e7-ice/.

Lutz Koepnick is the Max Kade Foundation Chair of German Studies and Professor of Cinema and Media Arts at Vanderbilt University in Nashville. Together with Jana Harper, he is the co-curator of Jessica Houston’s exhibition ". . . no footprints, even.", on view at the Vanderbilt University Museum of Art from January 30, 2025 to May 11, 2025.