Joseph A. Johnson Jr. became the first Black student to attend Vanderbilt University as the nation was on the cusp of profound change. It was 1953, a year before the U.S. Supreme Court’s historic Brown v. Board of Education decision that racial segregation in public schools, including public universities, was unconstitutional. It was two years before key turning points—the tragic lynching of Emmett Till and the courageous Montgomery Bus Boycott—in African Americans’ struggle for equal rights.

On Sept. 28, 1953, Johnson entered Vanderbilt as a special student in the School of Religion. He was 39 years old, a married father of three, and a pastor who wished to pursue a Ph.D. in theology. His acceptance to Vanderbilt by then-Chancellor Harvie Branscomb and the Board of Trust signaled both change and an evolving student body. Johnson earned a bachelor’s in divinity in one year, then after four years of graduate study received his Ph.D. in 1958, becoming the first African American to earn a doctorate at the university. In the preface to his Ph.D. dissertation, Johnson thanked Branscomb, Divinity School Dean John Keith Benton and the Vanderbilt Board of Trust, who “in 1953 opened the doors of a great university to qualified Negro students.”

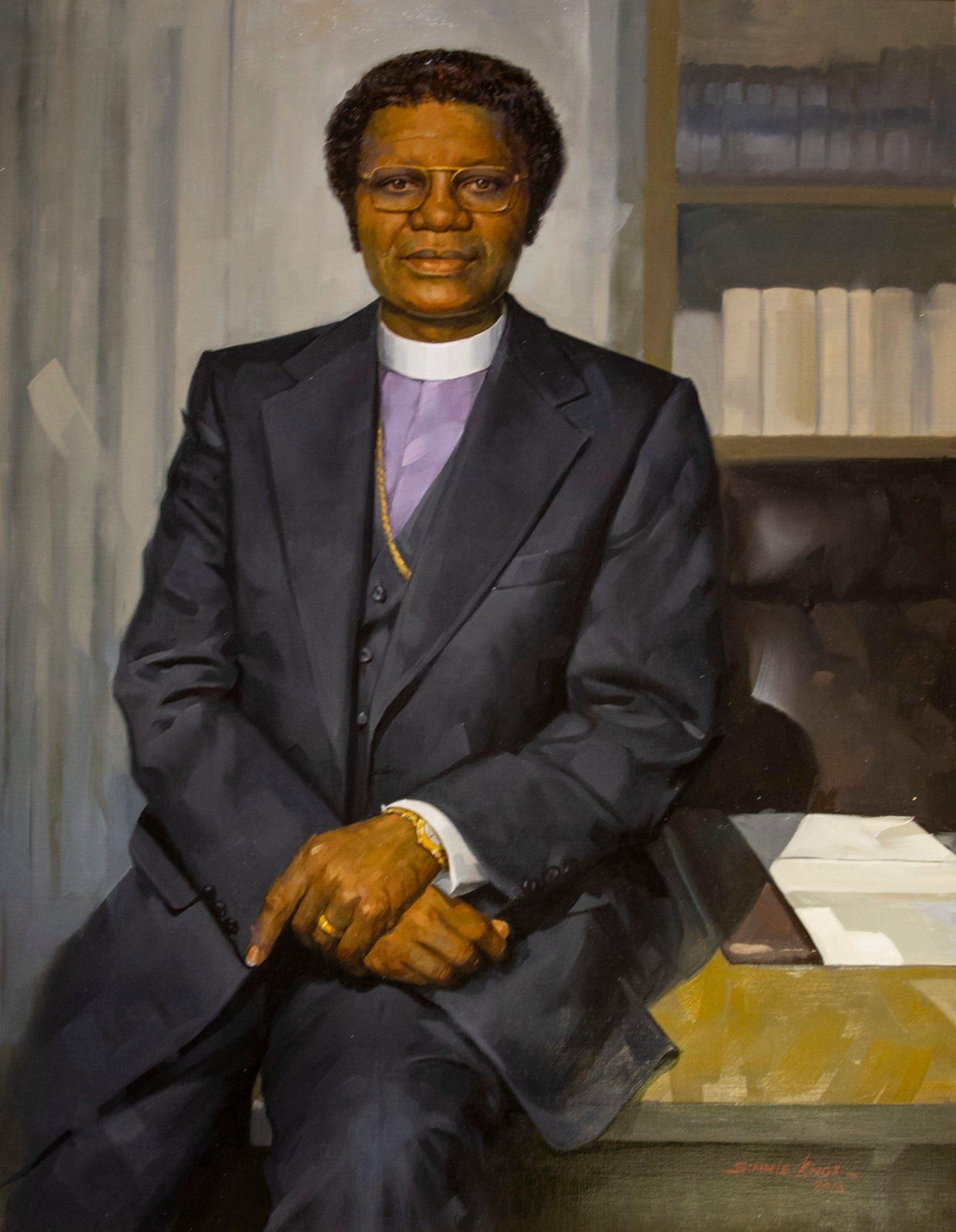

Johnson went on to be a professor of New Testament at the Interdenominational Theological Center in Atlanta and at Fisk University in Nashville. He later became a professor and eventually the president of Phillips School of Theology in Jackson, Tennessee. Johnson was made a bishop of the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church in 1966. By 1979 he was the presiding bishop of the Fourth Episcopal District in Mississippi and Louisiana. He authored six books, including The Soul of the Black Preacher, and worked on a new translation of the New Testament for two decades.

In the years following Johnson’s admission and graduation, Vanderbilt would periodically admit other Black students. Frederick T. Work and Edward Melvin Porter were the first African American students admitted to the law school in 1956, both graduating in 1959. While Vanderbilt’s graduate and professional schools had slowly opened their doors to integration, it was not until 1964 that the university admitted its first class of Black undergraduates. Those early Black undergrads—Robert J. Moore, Dorothy Wingfield Phillips, Diann White Bernstein, Maxie Collier, Earl LeDet, Norman Bonner and Randolph Bradford—helped pave the way for the Vanderbilt of today.

In 1971, Johnson became the second African American to serve on the Vanderbilt Board of Trust, which he did until 1979. He also served on the boards of Tyler College in Texas and Denver’s Iliff School of Theology. In 1984, Vanderbilt’s Bishop Joseph Johnson Black Cultural Center was renamed in his honor. In 2018, Johnson’s portrait was added to Kirkland Hall.